As a musician and music lover with a strongly developed sense of history, I have great respect for the late Alan Lomax and his work as a musicologist. This one man studied, recorded and preserved an improbably large share of the extant corpus of American folk music. The influence of his recordings and writings on the development of popular music in the late twentieth century is matched by no-one else, not even Bob Dylan. Indeed, without Lomax, Dylan might not even have existed. More broadly still, black American music might never have found a mass white audience if not for his efforts, which means the great creative explosion that resulted from this cultural conjunction couldn’t have happened without him either. The world owes Alan Lomax an incommensurable artistic debt.

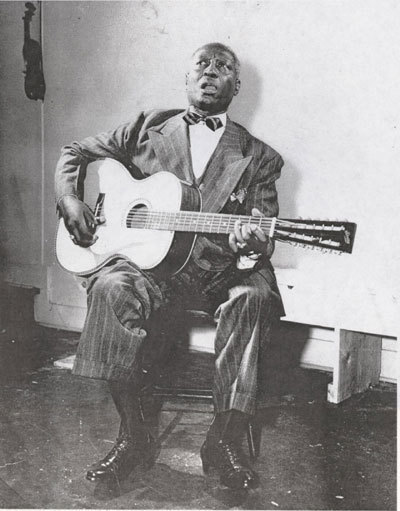

I was excited when I picked up this book. The little I knew about Lomax – about his shoestring travels across America with a recording machine in the trunk of his car, his risky encounters with redneck cops, prison wardens and the suspicious poor, his adoption of the blues singer Leadbelly, his troubles with Senator McCarthy and the FBI, his tireless championship of black causes, his purist rejection of artists like Dylan who put the material he had discovered and preserved to their own artistic uses – made him sound like a thoroughly fascinating character, the sort of man about whom it would be impossible to write a dull book. This, after all, was the man who ended up rolling in the dirt with Albert Grossman at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964 after Grossman caught him and Pete Seeger trying to take an axe to Dylan’s band’s power cable while they were on stage. How could a book about a man like that be boring?

Oh, easy. Just leave it to John Szwed. An associate of Lomax during the great man’s later years, his attitude towards his subject is one of obsessively hagiographic adoration. In this plodding, barely readable book, the arc of Lomax’s life-story is lost to view under an avalanche of irrelevant minor details. It is as if Szwed was determined to capture every move and gesture made by his subject, to describe and comment upon every essay, article, letter, postcard or shopping-list that Lomax ever wrote, regardless of its relative importance or thematic value. This suffocating mass of detail completely obscures what is really important in Lomax’s story. One of the most important traits of a biographer or historian is selectivity. Szwed appears quite incapable of it.

He is also incapable of admitting any serious faults in his hero, despite the evidence – given to us here in as much detail as everything else – that Lomax was manipulative, selfish and self-serving, and tended to exploit and betray the women in his life. The author finds excuses for it all. Lomax was academically and politically quarrelsome – but in this book it’s always the other guy’s fault. Szwed does not even scruple to slap on a coat or two of whitewash if the occasion demands it – having abandoned sequential reading about three-fifths of the way through the book, I skipped forward to see what the author had to say about the Newport incident, and discovered that he barely mentions it, and then only to dismiss it as ‘apocryphal’. This is simply untrue; several eyewitnesses have gone down in print with their descriptions, and there is no doubt that it happened.

This dreary book has only one redeeming quality, and that is the obsessive depth of its scholarship with respect to matters concerning its subject. Perhaps one day a real historian or biographer will find it useful as a compilation of primary sources from which to produce a really good biography of Alan Lomax. There’s no doubt that one is needed. This isn’t it.