Despite two assassinations in the previous thirty-six years, Presidential protection in 1901 was still not very good. Unfortunately, William McKinley found out just how vulnerable he was when Leon Czolgosz shot two bullets into him at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. McKinley lingered for about a week before dying, at first seeming to stabilize but then rapidly deteriorating due to gangrene. Scott Miller writes about the times and circumstances leading up to this long-ago and barely-remembered event. Miller takes us around the globe: Cuba, the Philippines, China, Japan; and around the country: Washington D.C., Canton, OH, New York, Pittsburgh, Chicago and of course Buffalo at the end.

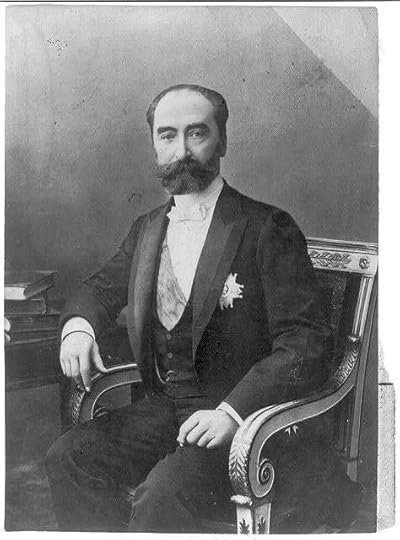

This is not a biography of McKinley, nor of Czolgosz (there would not be enough material to write a book solely based on this wretched man). Instead Miller focuses on important events that occurred and actions that McKinley took during his momentous first term in office. McKinley, initially not intentionally, helped usher in a new century for America - one in which the country would venture out across the globe, attempting to spread its "values" to peoples it considered inferior to itself, and putting a hand into the cookie jar labeled "Imperialism" multiple times. McKinley was not elected for that, and was lukewarm at best when he was first presented with avenues to expand U.S. influence. His attitude changed fairly rapidly though, sometimes with little justification for doing so.

McKinley, while not looking for war, seemed resigned to the fact that it would happen with Spain. Miller never successfully gets into his thinking; yes, McKinley did want to open up trade routes around the globe, and he supported Secretary of State John Hay's Open Door policy with China. But McKinley, a Civil War veteran himself, and very solicitous of the needs of U.S. troops, did not attempt to the pump the brakes on Theodore Roosevelt and others who were clamoring for war with Spain. Ostensibly, the U.S. used the (almost certainly) accidental explosion of the USS Maine as a pretext for war. In reality, it would seem beyond a reasonable doubt that the Spanish did not blow up the ship, that in fact it was due to spontaneous combustion of its coal supply. While this was determined decades later, even at the time of the incident, there existed no proof that the Spanish were behind the sinking of the vessel. Nonetheless, McKinley used it as a pretext to wage war. And for good measure, why stop with just Cuba? Get the Philippines too, was the thinking. They would be a nice possession, McKinley and Congress thought, following the recent U.S. annexation of the Hawaiian Islands.

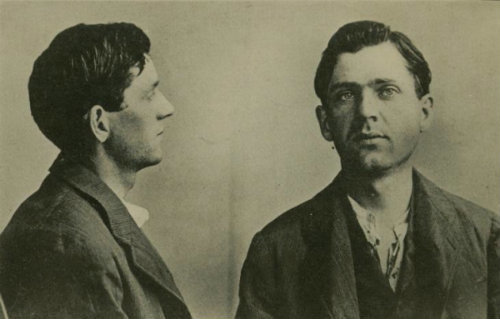

Miller also examines the anarchist movement, focusing in particular on the Haymarket riots, the Homestead strike, Alexander Berkman, and Emma Goldman. Czolgosz pops up in the narrative here and there, but he is almost a minor character throughout the book. Miller pays more attention to the nascent anarchist movement and how most Americans viewed anarchists. Czolgosz seemed to me to be at the fringe of the movement, much more so a loner than anything else. He was mildly lazy, working sometimes, loafing others. He was also a vagabond, bouncing around between Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, Buffalo and Akron. Czolgosz had no friends; even his family disliked him due to his disagreeable nature.

Also, and perhaps I missed something here, but I did not fully make a connection between Czolgosz and anarchism. He was not very active in their causes. While he did attend some meetings at intervals, he was viewed with suspicion by most of the other known anarchists. He did not evidence any hatred or intense dislike of McKinley prior to pulling the trigger of his revolver. So was he an anarchist? Or just a disgruntled loner? I am not really sure. Unlike Charles Guiteau (James Garfield's assassin) he was not judged insane or anywhere close to that. Honestly, he made me think of Oswald and his assassination of John F. Kennedy. Both of these men did not seem so much as to espouse any particular cause (although Oswald definitely held some Communist leanings) as to be nasty little men lived unhappy existences and made those around them unhappy.

Miller provides a nice epilogue, reviewing in brief all of the major areas that he covered in the book: anarchism, China, Cuba, the Philippines, the Open Door policy, Ida McKinley, American imperialism, and Goldman. The events of McKinley's presidency significantly altered America's role in global affairs, and while not making it a super power overnight, definitely set it on the path to becoming one by the end of WWII.

But ultimately this book did not fire on all cylinders for me. There was too much jumping around, both in timeline and in geography. Miller alternated chapters between the imperialist storyline and the anarchist movement. And among those, the location changed each chapter. So the result is that the reader is plunged into 1890s Cuba only to immediately be throw backward into Chicago twenty years before, then sent forward to the late 1890s but in China instead of Cuba, then back in time again, but this time to the early 1880s in Pittsburgh. It did not work for me. I am not opposed to alternating the storylines between chapters. Many writers do that well (Erik Larson is one that immediately comes to mind). But the shifting places and combined with the shifting in time, and then throw in different people being the focus from one chapter to another, made the narrative disorienting. The actual assassination itself, aside from the lead-up to it in the very beginning of the book, almost seems like an afterthought by the time Miller gets to it. In addition, he abruptly returns to the moment when McKinley is shot, in the middle of a chapter. Conceptually, this probably looked a lot better in an outline form than how the final product ended up.

Grade: C