What do you think?

Rate this book

172 pages, Hardcover

First published February 2, 2008

(…) planning homes, planning a homeland. Four walls around a block of air., wresting a block of air from amid all that burgeoning, billowing matter, with claws of stone, pinning it down. Home. A house is your third skin, after the skin made of flesh and clothes. Homestead.

His profession used to encompass three dimensions, height, width and depth; It was always his business to build things high, wide and deep, but now the fourth dimension has caught up with him: time, which is now expelling him from house and home.

“Home! he'd cried out like a child that would give anything not to be seeing what it was seeing, but precisely in this one brief moment in which he hid his face in his hands, as it were, even the dutiful German official had known that home would never again be called Bavaria, the Baltic coast or Berlin, home had been transformed into a time that now lay behind him, Germany had been irrevocably transformed into something disembodied, a lost spirit that neither knew nor was forced to imagine all these horrific things. H-o-m-e. Which thou must leave ere long. After he had swum his way through a brief bout of despair, the German official had applied to retain his post. those others, though, the ones who had fled their homeland before they themselves could be transformed into monsters, were thrust into homelessness by the news that reached them from back home, not just for the years of their emigration but also, as seems clear to her now, for all eternity, regardless of whether or not they returned.”

”As she looks back like this, time appears in its guise as the twin of time, everything flattening out. Things can follow one after the other only for as long as you are alive in order to extract a splinter from a child’s foot, to take the roast out of the oven before it burns or sew a dress from a potato sack, but with each step you take while fleeing, your baggage grows less and less, with more and more left behind, and sooner or later you just stop and sit there, and then all that is left of life is life itself, and everything else is lying in all the ditches beside all the roads in a land as enormous as the air, and surely here as well you can find those dandelions, these larks.”

”At some point the gong sounds, calling them all to supper. Then her granddaughter comes back up from sunbathing on the dock, humming quietly to herself just as she has done all her life, even as a little girl. Which means that in the end there are certain things you can take with you when you flee, things that have no weight, such as music.”

come to my blog!

come to my blog!

If I came to you,But she answers this in her next quotation, an Arabic proverb:

O woods of my youth, could you

Promise me peace once again?

When the house is finished, Death enters.To do the book justice, I would need to read it at least twice more. And probably to compare the original German, though Susan Bernofsky totally convinces me with her sensitive handling of language. For Erpenbeck writes like poetry or music, where phrases echo and amplify one another within a paragraph, a chapter, and the entire novel. I would want to read it all in one sitting, to enjoy the play of these references within a living whole. Then I would want to read it very slowly, with pencil in hand, to track the sequence of events and the ways in which the various characters relate to one another and to the house. But I suspect that Erpenbeck has precisely calculated the in-between state of a first reading, in which one senses the musical structure without tying it down, and feels the interconnectedness of the people without needing to reduce their lives to a linear story. This is a book like few others, a small masterpiece.

The landscape architects says: light and shade, open spaces and thickly overgrown ones, looking down from above, looking up from below. With the edge of his shovel, the gardener distributes the soil evenly across the bed. The vertical and horizontal must stand in salutary relationship to one another, the householder says...To tame the wilderness and then make it intersect with culture -- that's what art is, the householder says. With the edge of his shovel, the gardener distributes the soil evenly across the bed.There's a bit of internal rhyming there, with the repetition of spreading soil across the bed, and this turns up in several ways throughout the novel. Several descriptions find themselves popping up at different places, and literary springs tightened in the early chapters are released in the later ones.

When in 1939 Arthur and Hermine do apply for an exit visa after all, they sell Ludwig's property along with the dock and the bathing house for half its market value to the architect next door. On account of the profit he is making on this transaction, the architect pays the National Financial Authority a 6% De-Judification Gains Tax.This is genius. Most of us are aware that Jewish citizens of Europe, those that survived, found that everything they'd owned before the Second World War had been seized, sold, auctioned off and was irretrievable. But part of the horror of this is the utter normalization required to set up a special tax for this activity -- something most readers, or certainly this reader, had never given any thought to.

Hermine and Arthur, his parents.Most didn't make it out. The war intruded finally, on the land by the lake, in the form of invading Russians, at least one of whom left his seed to grow on the land by the lake.

He himself, Ludwig, the firstborn.

His sister Elizabeth, married to Ernst.

Their daughter, his neice, Doris.

Then his wife Anna.

And now the children: Elliot and baby Elizabeth, named for his own sister.

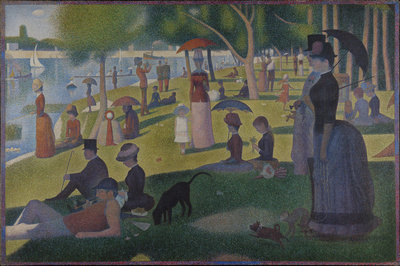

As the day is long and the world is old, many people can stand in the same place, one after the other. -- Marie in Woyzeck by Georg BuchnerThese quotes set the tone for what is about to be revealed, which is similar to seeing several photos of the same place superimposed onto one another, the people in it appearing like ghosts crossing over for a quick visit. Time is compressed in these narratives; the concern here is not only with objective linear time, but with time seen through the blurred lens of memory. And also with the disconnect between objective time (its brutal passing, regardless of us) and subjective time (our distortions, regardless of fact). The confusion that results is somewhat eerie. I’m having trouble coming up with examples, as she creates these effects over many pages. The chapter entitled “The Cloth Manufacturer” illustrates this very well, and can actually be read as an excellent standalone short story. Here is a sentence from that chapter:

If I came to you, / O woods of my youth, could you / Promise me peace once again? -- Holderlin

When the house is finished, Death enters. -- Arabic proverb

I know, he, Ludwig, says, his father’s only son.The chapters differ slightly in style depending on what each is saying, yet come together as a whole perfectly... and this chapter had one of the most distinctive styles. The sentences were short, declarative, often containing repetitive information cordoned off into dependent clauses that were then displaced at the end of the sentence. This displacement is intentionally jarring and sometimes awkward, but also the repetition of information had the tone of an ominous fairy tale, like the voice of someone trying to convey a horrible event to a child in the simplest way possible.

The replacement of the older narration by information, of information by sensation, reflects the increasing atrophy of experience. In turn, there is a contrast between all these forms and the story, which is one of the oldest forms of communication.This information moves along like time itself, relentless and unceasing like the endless seasons’ demands and the gardener’s constant work. Meanwhile, it is only the reader, with the advantage of having the entire book within reach, who is able to piece together the different narratives into a story. For each generation seems isolated from the ones before it and the ones to come, leaving only traces here and there, the scent of camphor and mint, but separated off like a dependent clause at the end of a sentence.

Home! he’d cried out like a child that would give anything not to be seeing what it was seeing, but precisely in this one brief moment in which he hid his face in his hands, as it were, even this dutiful German official had known that home would never again be called Bavaria, the Baltic coast or Berlin, home had been transformed into a time that now lay behind him, Germany had been irrevocably transformed into something disembodied, a lost spirit that neither knew nor was forced to imagine all these horrific things.In the middle of this book, the larger context of world history envelopes the smaller context of our story; we watch helplessly as our characters’ fates are dominated by the Holocaust and the war. We see time and place transformed by horrible events, distorted so that nothing is familiar. Nothing will be the same again. The consequence of linear time is its one-way-ness, we can never go back. And it is as if the novel pivots around this one point. We can never see these same places the same way, never associate them with the same uncontaminated memories.