What do you think?

Rate this book

400 pages, Paperback

First published December 1, 2006

But the really surprising thing about the painting is the way in which the figure of the gypsy is tilted forwards as though seen from above, in shallow relief. This device connects her pictorially with the 'flattened' vase and mandolin. There is something highly reminiscent of a Synthetic Cubist still life about this spatial invention, over twenty years before Juan Gris painted his Guitar and Fruit Dish (1921).Well, if the notes on individual pictures are not going to connect them up, you can at least group them in a meaningful order, like the thematic arrangement of individual rooms in a large gallery. But no. The pictures included in this book are in strict chronological order. So between the two Picassos, we get Winslow Homer, Emil Nolde, Wassily Kandinsky, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Franz Marc, and Henri Matisse—seven painters in all, showing almost as many different styles (there is some similarity between Kirchner and Marc). The tyranny of the calendar! It tells you nothing about "how to read a painting," though it may open your eyes to these particular ones. And whether it does depends upon the quality of the reproductions, which are mostly good, together with the relevance of the individual commentaries and the logic of the selection. Let's look at these:

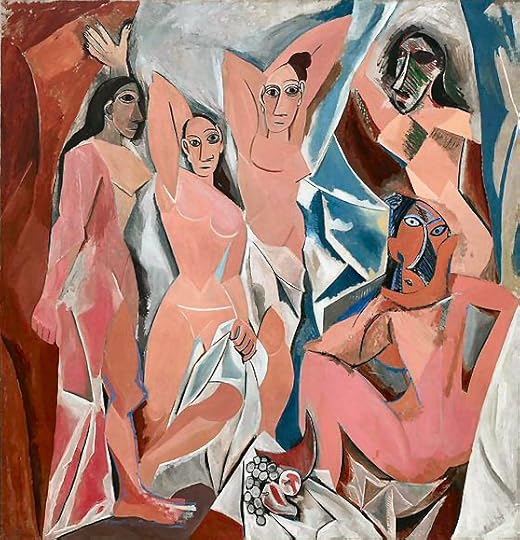

The image is simple. Five naked women disport themselves in various poses with a bowl of fruit in the foreground. The manner of realization is far from simple and is surprising, even today. Staccato, zigzag and arching lines make for a wild rhythm that takes over the whole picture surface. All traces of perspective have been eradicated. Flaring white brushstrokes shatter the tonal coherence of the painting. The art-historical discussion of sources and influences has been largely short-circuited by the idea of an unholy marriage between Cézanne and African art, even though the most cursory glance reveals nothing of Cézanne and only the occasional detail that might be said to be African in feel. The truth is—and it is evident throughout the painting—that there are many conflicting points of reference for the painting. Picasso was trying to recover the primordial life force through painting, and he looked to many so-called 'primitive' sources for his inspiration: Assyrian stone reliefs; funerary carvings from the early Athenian period; Boeotian bronzes and Cycladic figurines as well as African tribal sculpture, masks, and fetish figures.Thompson's style ranges from the verve of "Staccato, zigzag and arching lines make for a wild rhythm that takes over the whole picture surface" to the gauche repetitions of the word "painting." But his information is potentially valuable; it would be more so if he backed up his dismissal of Cézanne by reference to some other page in his book, or if most of his readers had any idea of the "primitive sources" he lists at the end. He would be good at sparking discussion with graduate students, but as an introductory exposure to the basics promised in the title, his notes miss the mark.

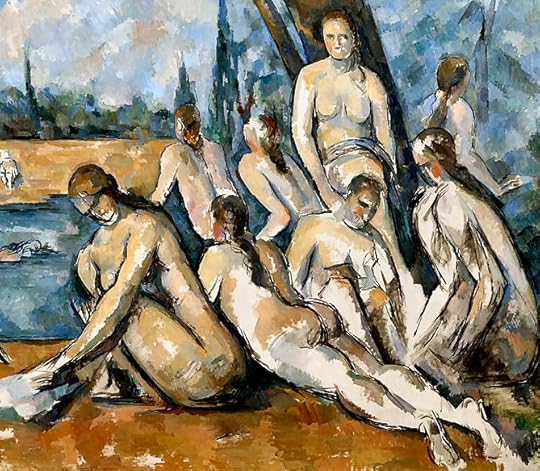

With its hacked countours, staring interrogatory eyes, and general feeling of instability, Les Demoiselles is still a disturbing paining after three quarters of a century, a refutation of the idea that the surprise of art, like the surprise of fashion, must necessarily wear off. No painting ever looked more convulsive. None signalled a faster change in the history of art. Yet it was anchored in tradition, and its attack on the eye would never have been so startling if its format had not been that of the classical nude; the three figures at the left are a distant but unmistakable echo of the favourite image of the late Renaissance, the Three Graces. Picasso began it in the year Cézanne died, 1906, and its nearest ancestor seems to have been Cézanne's monumental composition of bathers displaying their blockish, angular bodies beneath arching trees. [See detail below]

By leaving out the client, Picasso turns viewer into voyeur; the stares of the five girls are concentrated on whoever is looking at the painting. And by putting the viewer in the client’s sofa, Picasso transmits, with overwhelming force, the sexual anxiety which is the real subject of Les Demoiselles. The gaze of the women is interrogatory, or indifferent, or as remote as stone (the three faces on the left were, in fact, derived from archaic Iberian stone heads that Picasso had seen in the Louvre). Nothing about their expressions could be construed as welcoming, let alone coquettish. They are more like judges than houris. And so Les Demoiselles announces one of the recurrent subthemes of Picasso’s art: a fear, amounting to holy terror, of women. This fear was the psychic reality behind the image of Picasso the walking scrotum, the inexhaustible old stud of the Côte d’Azur, that was so devoutly cultivated by the press and his court from 1945 on. No painter ever put his anxiety about impotence and castration more plainly than Picasso did in Les Demoiselles, or projected it through a more violent dislocation of form. Even the melon, that sweet and pulpy fruit, looks like a weapon.With writing like this, who would not start to read pictures differently? Hughes realized that "a generalized and speckly tour d'horizon" was useless for television, and instead opted for eight essays, each taking a specific theme and pursuing it across a wide historical front. A few years earlier, the BBC made a series called Connections, in which historian James Burke tied scientific discoveries together in extraordinary ways, often spanning centuries. Though more narrowly focused, Hughes makes similar connections, not only between artworks, but between art and the history and culture within which we ourselves, our parents, and perhaps our grandparents have lived. And he did it on a popular level, without ever talking down.