What do you think?

Rate this book

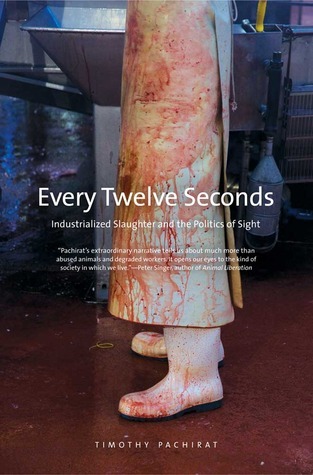

320 pages, Hardcover

First published November 8, 2011

There's a silence in the room. I am on dangerous ground, but the conversation is intoxicating. It is more than just the desire to impress them so that I can get the job. After working in the complete silence of the cooler, I have an uncontrollable urge to show the management that we are not just stupid, mindless machines turning our gears day after day, to show them that we too have thoughts and feelings (171).

The result of the audit is to transform a physical confrontation with the killing of live creatures into a technical process with precise measurements of when the procedure counts as humane and ethical and when it does not. The inspector is looking directly at the animals; he or she is listening to their voices, but they are seen and heard only as criteria within a technical process, as data point.

The very question 'For who could stand the sight?' becomes historically intelligible only in the context of a 'reign of opinion' dependent for its existence on the continued operation of distance and concealment, the continued hiding from sight of what is classified and repugnant (252).

Concerned with the subjecting power of a generalized gaze, some will dismiss the ideal, like vision itself, as a trap. Others, placing their faith in a weight of opinion and the immutable timelessness of pity, will energetically advance the project of bringing every dark thing to light, demolishing every distance between what is seen and what is hidden (254).