The dilemma of any historical novel is the question: Is it history or literature? No doubt, in part due to Shakespeare, most English-speaking readers have a confident familiarity with the English monarchial succession: Richard II, Henry IV (Bolingbroke), Henry V (Prince Hal), and Henry VI. The narrative arc and heroic-tragic framework create a compelling literary treatment of the Hundred Years' War. Aside from Jeanne d'Arc, however, the dramatis personae on the continent remain obscure.

Haasse's historical stage is France rather than England. However, her narrative is disparate. Her central character is Charles, Duke of Orleans. He had an unusually long life that spanned nearly three quarters of a century. He endured — through four generations of Burgundian dukes, through the reigns of five English kings, and through the reigns of four French kings. At age 13 he wed his first cousin Isabelle, age 16, the widow of King Richard II of England and the daughter of King Charles VI (“the Mad”) of France. He fought at the Battle of Agincourt, but then remained an English prisoner for 25 years. He is a passive introspective character, a writer of poetry and reader of books. Much of his role is that of victim — of political setbacks, depleted treasury, collapsed alliances, and personal enmities.

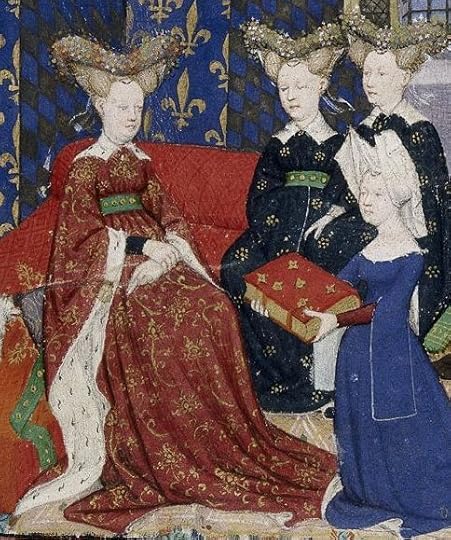

Women dominate the first section of the book. The book opens with Valentine, Duchess of Orleans and mother of Charles, receiving the formal greetings of her brother-in-law the king after the christening of the newborn Charles. In those few opening chapters Haasse conveys an indelible picture of Charles “the Mad”, who throughout his long reign (1380 to 1422), suffered extended delusional attacks; his shrewd embittered wife Isabeau of Bavaria, and the king's paternal uncle Philippe, Duke of Burgundy, ambitious, cold and crafty. We watch Valentine's transformation from sensitive dutiful wife to a woman crushed by the unfulfilled desire for vengeance. One of the most intense scenes is the deathbed vows she extracts from her sons. As for Isabeau, Haasse describes her regarding her children: “It was the love of a chess player for the precious pieces on her board; in it there was no trace of tenderness, of concern with the thousand little joys and sorrows of a child's life....” (Location 1466) Of course, like every other parent, she will come to learn that unlike chess pieces, children cannot be controlled.

An intriguing woman also appears in the final section of the book. Isabelle of Portugal, the third wife of Philip III (“the Good”) of Burgundy appears and becomes a primary force in effecting Charles' release.

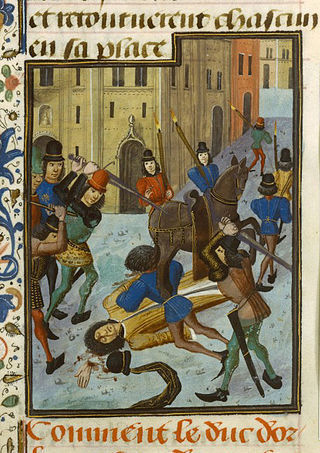

Charles d'Orléans is eclipsed in the next section of the book as well. The narrative up to the Battle of Agincourt focuses on the constantly shifting political landscape. As Americans, we possibly tend to look at civil war as a conflict between two well-defined forces. The French civil wars were ugly conflicts with multiple competing factions engaged in opportunistic alliances and betrayals. Out of necessity, Charles' chief ally is his father-in-law, Bernard d'Armagnac. Haasse depicts the coarseness of Armagnac in a passage that combines her own appraisal with that of one of her characters: “Around him hovered an acrid odor of hay, dogs and horses, of smoke and sweat. He reminded [Jean d'] Berry of a beast of prey: the blazing yellow eyes, the hairy wrists, and sharp eyeteeth could scarcely be termed human.” (Location 4585) The Houses of Burgundy, Armagnac, Brittany, Anjou, Bourbon and Berry; allies in Sicily, Milan, Genoa, Flanders, Hungary, and Bavaria; a succession of Dauphins; bands of Parisian tradesmen; and Queen Isabeau are busy cutting deals, even with the enemy England, to enhance independent self-interest. This political turmoil continues to unfold offstage like a Greek drama during the 25 years of Charles' imprisonment. Haasse employs ingenious and entertaining strategies for relating this to the reader. (As an Enlish pawn and captive, Charles is kept incommunicado).

Haasse maintains a delicate balance between what the reader knows and what her characters know. At times this strategy is unsuccessful. It is only after his capture and imprisonment that Charles has an epiphany. “Those in authority contested each other's crown and scepter; they were motivated only by greed. That wolves devoured the flock, that brigands plundered the pilgrims, that thieves and murderers did their work, that famine and pestilence destroyed the people with sharp scythes — these were no concern of princes and prelates. The more Boucicaut talked to him about the obligation of monarchs and nobles to protect the defenseless people, the more Charles thought he saw the reality depicted in glaring colors; an intense fear for the future of his country crept over him.” (Location 6443) This reality has been obvious to the reader from the outset.

The concluding passages of the book require some implicit knowledge on the part of the reader. The new King of France, Louis XI, Charles d'Orléans' grand nephew through his first wife, Isabelle, sneers: “What have you, with all your good will and so-called wisdom, understood of the evolution we have undergone — of the real significance of the struggle which has been going on since my great-grandfather's [Charles V] day — between the Crown and the powerful forces who want to smash it to pieces?...Henceforth there will be one King in France...and that King will rule from the Pyrenees to the farthest border of the lowlands.” (Location 10300) It is an astute assessment of history. Yet, the King's evaluation of Orléan's insignificance, a wasted life in his estimation, is unsound even by his own standards. The reader is expected to know that Louis XI's son Charles VIII would die at an early age without an heir, and Charles' son Louis of Orléans, would succeed him as King Louis XII of France. These events are an ironic confirmation of Charles d'Orléans' declaration that the pursuit of power is a wandering in the dark wood, a groping of the blind. His life has not been in vain. He has experienced love, has had children to cherish, has found expression through poetry and learned to find happiness in being connected to the natural world. In the end, there is a kind of poetic justice.

Returning to my original question, this novel is more history than literature. The life of Charles d'Orléans provides structure to the novel, but he is never a compelling central character. Not being a speaker of French, I found it hard to appreciate his poetry. His early separation from his second wife Bonne came across as maudlin. The political intrigues were too fascinating to be relegated to the background, but started to lose focus during the period of Charles' exile. Nevertheless, Haasse instills life into her characters and imposes clarity and color on what would otherwise be a long catechism of names, dates and events. She creates convincing dialogue that supports her views of these characters while conveying a sense of period authenticity. She is meticulous in her descriptions of protocol and court etiquette, beneath which a facial tic or double entendre can convey mischievous malice. Her references to religion, of sin and retribution, reflect a believable range of attitudes.

I read this book because after reading THE NAME OF THE ROSE (whose events occur in 1327). I was curious about the middle ages from the perspective of the continent. My curiosity has been increased after having read this book.

NOTES

The novel is prefaced with both a “Cast of Major Characters” and genealogies for the French Royal House of Valois (the line of Charles VI of France), the House of Orléans, the House of Berry and the House of Burgundy. Four of the major characters are named Charles, three are named Philippe, and three are named Jean. The families are so intermarried that the separate family trees are a necessity to avoid a spaghetti-like tangle. I found it useful to create my own multi-generational family trees: Burgundy, Orléans, Valois, the English succession, and Anjou.

Key Dates

Sept. 16, 1394 Avignon pope Clement VII dies

Nov. 24, 1394 Charles d'Orléans born

April 22, 1404 Philippe (the Bold), Duke of Burgundy dies

June 29, 1406 Charles d'Orléans and Isabelle of Valois wed

Nov. 23, 1407 Louis, Duke of Orléans murdered

Dec. 4, 1408 Valentine, Duchess of Orléans dies

Sept. 13, 1409 Isabelle Valois, first wife of Charles d'Orléans dies

March 20, 1413 Henry IV of England dies

Oct. 25, 1415 Battle of Agincourt

Sept. 10, 1419 Jean, Duke of Burgundy murdered

Aug. 31, 1422 Henry V of England dies

Oct. 21, 1422 Charles VI (“the Mad”) of France dies

May 23, 1423 Avignon Pope Benedict XIII dies

July 17, 1429 Charles VII crowned King of France

May 30, 1431 Jeanne d'Arc burned at the stake

July 2, 1440 Charles d'Orleans freed from captivity

July 22, 1461 Charles VII, King of France dies; Louis XI ascends French throne

Jan. 5, 1465 Charles d'Orleans dies

Aug. 30, 1483 Louis XI, King of France dies

April 7, 1498 Charles VIII, King of France dies; succeeded by Louis d'Orléans (Louis XII)