What do you think?

Rate this book

428 pages, Paperback

First published October 31, 2006

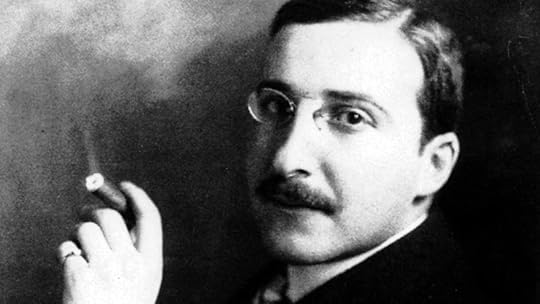

A great deal had to happen, infinitely more in terms of events, catastrophes and trials than has fallen to any other single generation, before I found the courage to embark on a book in which I myself am the main character, or rather the focal point. But nothing could be further from my mind than the desire to thrust myself forward, unless it be in the role of one who presents a slide show. The images are furnished by the times, I merely speak the words to accompany them: and the story I shall tell will not be so much my own personal destiny, but rather that of an entire generation – a unique generation, that has been burdened with destiny like no other in the course of history.