What do you think?

Rate this book

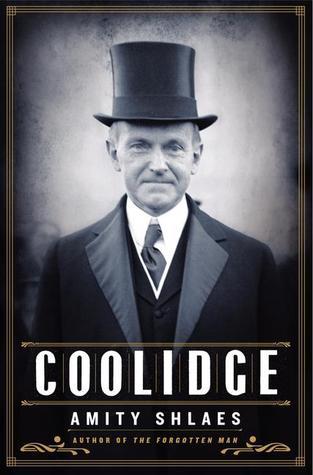

536 pages, Hardcover

First published February 4, 2013

Despite Amity Shlaes hitting all the requisites for a good biography, Calvin Coolidge has earned a spot on my meh list (though, rumor has it, such lists are, themselves now considered ’meh’). Maybe I was biased by his little stern, lipless face but he just never struck me as being all that likable.

I’m by no means an anomaly in my tepid response to Silent Cal. It seems that, back in the day, Amherst College had quite the Greek Life going (surprising unto itself). However (and you’ll have to excuse my lack of fraternity lingo knowledge here), “brothers” weren’t exactly clamoring to let Calvin into their pledge classes. In fact, Calvin proved to be a deal breaker when a friend tried to broker a two-for-one deal Sophomore year. I (now) know Amherst has fraternities and whatnot, but the amount of time spent on this suggested an environment more akin to Animal House than a New England liberal arts school.

At Amherst, Coolidge attended a riveting course or two, learned a bit about public speaking and wrote a bunch of letters home needling for extra cash in a circuitous manner. It sure would be nice if I had a bit more to spend as life here is rather expensive. (This last bit is notable given his devotion to thrift in his later life.)

As Calvin came out of his shell he acquired powerful friends who devotedly champion him throughout his life (Frank Stearns, some dude who worked at J.P. Morgan and Crane of Crane & Co. which is notable if you’re into stationary). Stearns tried to get Coolidge to dip a toe into the right social circles- difficult, I guess, due to Calvin’s intense frugality.

Fast forward to Calvin Coolidge becoming VP to Warren Harding who, then, kicked the bucket, making Coolidge the president (I’m just clarifying for those of you who were deprived of School House Rock and, thus, have no understanding of our political system whatsoever). Calvin was really into slashing the budget, cutting taxes and “saving the government’s money rather than spending it.” This is not the element of Coolidge’s frugality that I found annoying. He was a spendthrift in every element of his life- a poor tipper, he berated the White House staff for ordering too many hams for a big dinner. I got the sense that people were afraid of him- the game wardens of South Dakota stocked the lakes with fish for Coolidge’s vacation there to ensure his angling success.

Having read Five Days at Memorial, I may have been overly sensitive to Coolidge’s callous response regarding federal aid for a Mississippi River flood in 1927 (the Katrina parallels were painfully evident). I think Michael McLean’s Mini Dove Comic (which are always awesome) sums it up pretty well:

I’m not a sufficiently astute student of economics to analyze Shlaes’ specific theses on the impact of the Coolidge approach to federal finance, but I certainly got the feeling it was one-sided (Jacob Heilbrun’s New York Times review might provide more insight).

Coolidge did not run for a second term, and died not that long after the end of his presidency. The conclusion was lackluster which pretty much parallels the last years of Calvin’s life.