It was a lovely, chill, pine-smelling valley, as lonely as you could want.

The Ox-Bow is a charming place somewhere high up in the Arizona Mountains, empty for most of the year and used rarely as a resting place by the stagecoach or by passing cowboys. In the spring of 1885 this little known meadow is witness to a lynching.

Twenty-eight angry men set out from the cattle town of Bridger’s Wells to hunt down and to deliver a piece of frontier ‘justice’ to the alleged rustlers who have stolen cattle from the range and left a man dead in a ditch. One among them, Arthur Davies, is there to convince the others to follow the true law and bring the men back to town to be judged properly.

Can his arguments convince these rough settlers and cowboys to stop and think about what they are doing? Or will they cling to the myth of the West and the righteousness of the vigilante who takes the law into his own hands?

Wallace Stegner, a writer who sits very high in my literary pantheon, writes the introduction of this debut novel from mr. Clark and helpfully underlines the true significance of the effort to define civilization in opposition to the populist trends that romanticize the brutality of the Westward expansion.

To Signet and Signet readers, it is a novel of excitement and suspense and nervous trigger fingers. They do not read it as the report of a failure of individual and social conscience and nerve, an account of wrong sanctioned and forced by the false ethics of a barbarous folk culture.

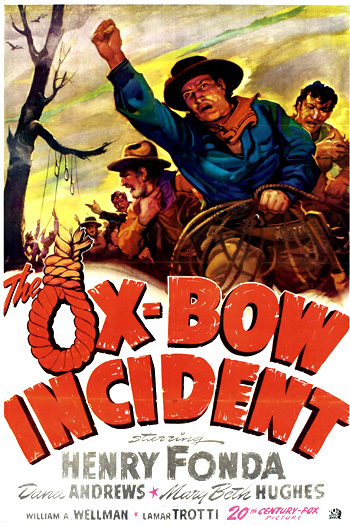

Reading about some remarks from Henry Fonda, who rates his role in the movie adaptation of the novel as his all-time favourite, alongside the “Grapes of Wrath”, my recollection goes instead to another movie that treats the same subject as a court drama: “Twelve Angry Men”. This memory was also triggered by early efforts from Arthur Davies to delay or stop the vigilante crowd from setting out in pursuit until the law , represented by the local Sheriff and Judge, can take over. Davies argues that it is better to let a hundred guilty people go rather than condemn an innocent one, but such arguments are decades ahead of their times in Bridger’s Wells.

“If we go out and hang two or three men, without doing what the law says, forming a posse and bringing the men in for trial, then by the same law, we’re not officers of justice, but due to be hanged ourselves.”

“And who’ll hang us?” Winder wanted to know.

“Maybe nobody,” Davies admitted. “Then our crime’s worse than a murderer’s. His act puts him outside the law, but keeps the law intact. Ours would weaken the law.”

The novel is narrated by Art Croft, a cowboy who comes down to town with his pal Gil Carter after a long winter spent on the range. They are caught in the events as they sit and drink and play cards in Canby’s saloon, a place where suspicion and male posturing and barely contained violence set out the mood for the drama even before the cattle rustling and the murder are discovered. Art and Gil feel the wrongness of the mood right from the start, but they are unwilling to confront the loud voices of hatred for fear of being considered cowards or weak.

Thinking about it afterwards I was surprised that Bartlett succeeded so easily. None of the men he was talking to owned any cattle or any land. None of them had any property but their horses and their outfits. None of them were even married, and the kind of women they got a chance to know weren’t likely to be changed by what a rustler would do to them. Some out of that many were bound to have done a little rustling on their own, and maybe one or two had even killed a man.

Privately, Art Croft agrees with Davies, and would like to see the Judge and the Sheriff take over and absolve him of responsibility for what is going on, but the instinct to be a part of the crowd is stronger.

Then he said a lynch gang always acts in a panic, and has to get angry enough to overcome its panic before it can kill, so it doesn’t ever really judge, but just acts on what it’s already decided to do, each man afraid to disagree with the rest.

Another accurate and disturbing observation of the author, put in the mouth of Davies, is that any such crowd of angry people need a focus, a leader, before it acts. Such a leader, and a self-appointed one at that, is the rancher Tetley, a former Confederate officer who doesn’t have any direct relation with the victims, but seizes the opportunity to inflict some damage without repercussions. Tetley is a bully, as are some of the other ring-leaders of the gang, and is particularly vicious towards his teenage son Gerald, a sensitive young man who abhors violence on principle.

“Only two things mean anything to Tetley,” he said, “power and cruelty. He can’t feel quiet and gentle things any more; and he can’t feel pity, and he can’t feel guilt.”

The scene is set, the actors have been introduced, and a storm is approaching the cattle town as the twenty-eight men set out towards the high mountain pass that leads to the Ox-Bow meadow. Darkness and freezing cold and angry voices combine to instil a sense of doom that explodes in senseless violence as the possy meets the stagecoach coming from the other side of the pass, before they even come across three strangers and a herd of cows in Ox-Bow.

It’s quite easy to see why this has been sold by the marketing teams of the publishers as an action / adventure genre novel. Walter Clark is a great storyteller, capable of fleshing out a character and a scene with a few well-chosen words, the emotions and the actions are convincing and hard-hitting. Maybe the only exception is Arthur Davies, whose eloquence on the subject of justice is a little too studied, too articulated for such a rough setting. But even Davies is saved in the end by his scruples and by his willingness to self analysis in the aftermath of the Incident.

I knew Tetley could be stopped then. I knew you could all be turned by one man who would face Tetley with a gun. Maybe he wouldn’t even have needed a gun, but I told myself he would. I told myself he would to face Tetley, because Tetley was mad to see those three men hang, and to see Gerald made to hang one of them. I told myself you’d have to stop him with fear, like any animal from a kill.”

The subject of lynching and of standing up to bullies before they assume power over you is I believe as relevant today as it was in 1885, or in 1940 (the year the novel was published and when Hitler was already a real concern). Consider only the fact that 2022 is the year that the US Congress took a vote on a law that specifically prohibits lynching, a law that was introduced more than hundred years ago. Consider also the case of the young man who was recently killed by vigilantes while jogging through a suburban neighbourhood.

In Bridger’s Wells, the only open and unreserved support Arthur Davies receives comes from the town’s only coloured man, an odd jobs pauper known as Sparks.

“Ah saw mah own brothah lynched, Mistah Croft,” he said stiffly. “Ah was just a little fella when I saw that, but sometimes ah still wakes up from dreamin’ about it.”

Most parts of the world, you don’t need to witness a crime in order to know it is wrong. Walter Clark is probably trying to mark in his first novel the transition from the law of the gun to the law of the land. In my opinion, he has done a masterful job, one that transcends genre limitations and speaks truth across generations.

True law, the code of justice, the essence of our sensations of right and wrong, is the conscience of society. It has taken thousands of years to develop, and it is the greatest, the most distinguishing quality which has evolved with mankind. None of man’s temples, none of his religions, none of his weapons, his tools, his sciences, nothing else he has grown to, is so great as his justice, his sense of justice. The true law is something in itself; it is the spirit of the moral nature of man; it is an existence apart, like God, and as worthy of worship as God. If we can touch God at all, where do we touch him save in the conscience? And what is the conscience of any man save his little fragment of the conscience of all men in all time?