What do you think?

Rate this book

178 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1995

Sometimes it's called homesickness; sometimes it's the arid, high-altitude wind that tugs at your nerves; sometimes it's the alcohol, sometimes worse poisons. Sometimes it has no name…

I put my glass down by my deckchair and went out. The door was just a frame with a mosquito net stretched across it. The sensation was familiar, pushing aside the thin partition that separated a room filled with peaceful, lamplit warmth from the great surrealism that lay outside—the moonlight, the gleam of the desert, the strips of ground you could cross up to the starkly white, rocky ridges, the place of royal tombs where ibex spent the night and foreign ships with paralysed sails lay for eternity.

‘You cannot move,’ said the angel pleasantly, ‘you are utterly helpless and exposed to the angels of this land, who are terrible creatures.’

‘You know very well that no one can enter the heart of another and become as one, not even for the shortest moment. Even your mother only made you flesh, and at your first breath you breathed in solitude.’

Afinal, não foi por uma questão de consciência que deixei a Europa e o meu país? Passaram já dois anos. Naquele tempo, tinha chegado o momento da decisão e da luta por uma causa, mesmo para quem não tivesse escolhido a grande discórdia que separa os povos e envenena os homens. Observar passivamente seria falta de consciência, e isso eu não tolerava. Ainda menos queria lutar, parecia-me falso o papel que outros esperavam que eu representasse. Sim, deixei o meu país por uma questão de consciência, e muitos invejaram a minha liberdade e a minha escolha.

Mas aqui a própria liberdade perde o sentido. Já não espero nada da minha liberdade, quero apenas regressar, mas não posso, não posso, e sei que não posso.

(...)quem hoje vive num país europeu sabe como muitos não resistem à tensão atroz, uma tensão que se estende do conflito pessoal entre a necessidade de repouso e a capacidade de decisão, que se estende da necessidade material mais simples e inadiável às questões mais gerais e no entanto prementes da política, do futuro económico, social e cultural, uma tensão a que ninguém escapa ileso. E se, não obstante, a juventude tenta escapar ilesa, por conscienciosa que seja no modo como interpreta a sua fuga, ainda assim traz na testa a marca de Caim, a marca de quem traiu o irmão.

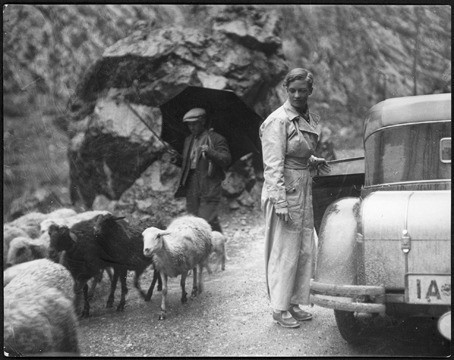

-Quatrocentos quilómetros - disse ela. - Mas tu não fizeste já esta viagem?

-Precisamente por isso - respondi, - na primeira vez ousamos tudo, porque não conhecemos a modéstia. Mas depois, depois não devemos cair em tentação outra vez.

-Quanto a isso - disse Barbara, - fui eu quem te fez cair em tentação. Fui eu quem te convenceu a fazer esta viagem. Não me digas agora que estás arrependida!

-De qualquer maneira, teria tentado outra vez.

-De qualquer maneira?

-É que neste país temos de estar duas vezes certos das coisas que amamos.

-Uma defesa contra esta impressão de estarmos a sonhar?

-Sim - disse eu, - faz-me medo. Tenho medo do efémero.

Mas já só o nome de Persépolis era imperecível e intocável, e ninguém podia esquecer a visão das suas ruínas.

-Este país faz de nós cobardes - disse Barbara.

Naquele tempo, eu não conhecia esta sensação nova. Só mais tarde compreendi, quando se tornou demasiado poderosa e quase me aniquilou. E desde então, sobre a desolação magnífica e sobre o excesso de cores daquelas terras, sobre a sua recordação em parte transfigurada e em parte terrível, desde então que paira acima de tudo, como uma cortina de fumo, o medo sem nome.

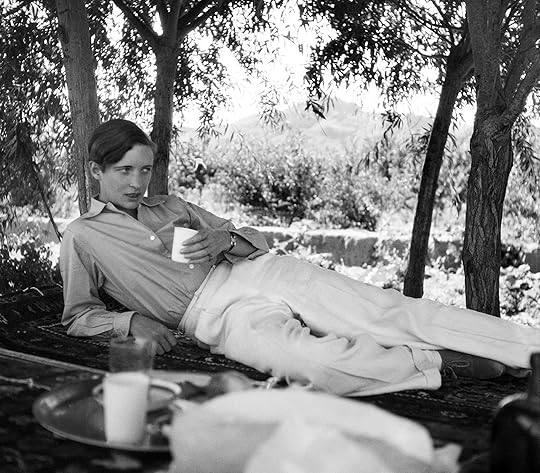

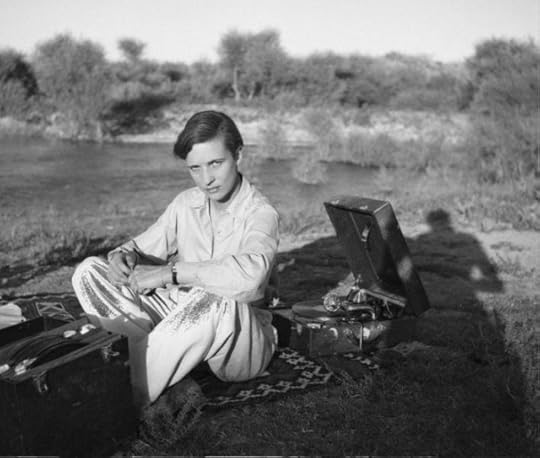

O que acontece quando uma pessoa chega ao fim das suas forças? (Não é doença, não é dor, não é infelicidade, é pior.) Numa manhã, ela senta-se diante da sua tenda e olha para lá do rio(...)Pensamos em levantar-nos, endireitar as costas doridas. À tarde, quando nos estendemos na cama de campanha, no interior quente e sombrio da tenda, percebemos que o repouso não é possível. E depois o pavor desesperado das horas nocturnas! Também elas passarão, e um novo dia chegará(...)Mas o que fazer? Não havia, ontem ainda, tanto que fazer?(...)O que foi que mudou desde então? Erguemos devagar a mão e cerramos o punho. Impossível cerrar o punho. O gesto é fraco, choco, e nas costas, nos joelhos, na nuca sentimos já a terrível prostração da acédia, uma doença pior que a malária. As mãos estão húmidas, falar é um esforço desmedido. Levanta-te e caminha! O coração bate depressa, e seguimos pela margem do rio mais depressa ainda, para não cedermos à tentação de nos atirarmos ao chão e chorarmos de cansaço e desespero. Aha, aqui não se chora. É pior, muito pior. Aqui estamos sós.

Sabes bem que ninguém pode entrar no coração de outra pessoa e unir-se a ela, nem sequer por um breve momento. Mesmo a tua mãe deu-te apenas um corpo, e quando começaste a respirar, não foi ar que inspiraste, mas solidão.

(...)gritarás e chorarás, porque não poderás fazer mais nada. Assim são os homens, hoje e há séculos atrás e há milénios atrás, sempre se revoltaram quando já nada lhes restava.

Ainda me lembrava de noites como esta, a mesma embriaguez, a mesma serenidade, a mesma tristeza, o mesmo desassossego diante do silêncio sobre-humano e desapaixonado deste lugar.

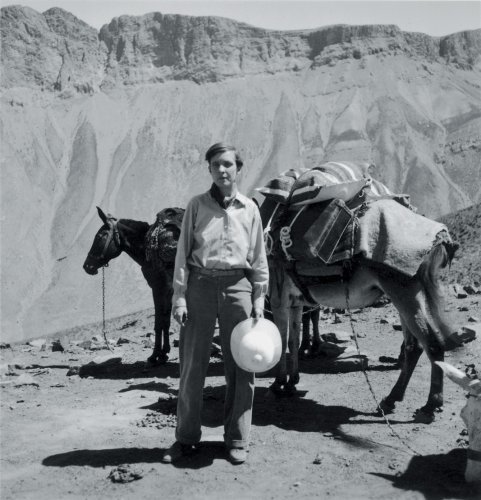

Quem foi que me trouxe até aqui? Porque tive eu de percorrer tantos caminhos, de me perder uma e outra vez? Primeiro, por aventura, depois por saudades, depois porque comecei a sentir medo e ninguém me ajudava. Ah, mas é verdade que alguém me expulsou, quero acusar, quero denunciar, não quero que digam que sou eu a responsável, não quero que me deixem morrer aqui sozinha, quero que me levem para casa!

Mãe, pensamos (como este nome ajuda a chorar!), fiz qualquer coisa mal, logo no início. Mas não fui eu, foi a vida. Todos os caminhos que percorri, todos os caminhos que não percorri, terminam aqui, no «vale feliz», donde não há saída, e que por isso se assemelha já ao lugar da morte.

Ah, despertar mais uma vez sem sentir as suas garras, por uma vez não ficar só e entregue ao medo! Sentir a respiração feliz do mundo!

Ah, viver mais uma vez!

We had wanted to talk about happiness and didn't notice that we were thinking about death…reminded me of Charles Simic. There's an angel as haunted as anything in Rilke or Wim Wenders. This is a spare book of prose, a travel diary that reads like sustained poem, an Arabian Night of pure fear and terrifying beauty.