Six Stars ! what a thought-provoking book that reframes how we think about human evolution. One of its most striking ideas is the transition from pre-human movement to fully upright Homo sapiens, and the central role of the glutes in that shift. Strong, well-formed glute muscles enabled upright walking, agility, balance, and explosive movement, while freeing the hands for coordination and dexterity—almost like becoming natural boxers. This resonates strongly with modern sport, particularly football and boxing, where glute strength underpins speed, power, and control.

Another compelling section describes the discovery of baboon skulls found together in a pit, all bearing identical injuries. Radiocarbon dating showed this occurred hundreds of thousands of years before Homo sapiens. The evidence suggests pre-humans used a femur bone as a weapon, striking the same point on the skull—likely reflecting right-handed attackers. This represents one of the earliest known examples of organised tool use and collective violence. This was another massive point the book makes : “Many a zoologist today, after a generation of accumulated studies, will flatly assert that the territorial compulsion is more pervasive and more powerful than sex.”

Here are the best bits:

The paramount distinction between human and animal intelligence, so far as we know, lies not in complexity, or profundity, or creativity, or memory, but in man's capacity for conceptual thought, and his power to see ahead.

Similarly, the special development of that mass of muscle centred in the human buttocks makes possible agility and all the turning and twisting and throwing and balance of the human body in an erect position. As the brain co-ordinates our nervous activity, so the buttocks co-ordinate our muscular activity.

Not for a moment did Darwin interpret the early human contest as one between individuals. In his Descent of Man he saw early man as definitely a social being, and any contest in such primal times as one between communities. He saw the tribe as a "corporate body" entrusted by nature with a set of genes differing from that of any other tribe; and natural selection as a contest between such tribes, each of which by evolutionary necessity must maintain its integrity through an infinity of generations. In his Letters he wrote: "The struggle for existence between tribe and tribe depends on an advance in the moral and intellectual quality of its members." Again, in the Descent of Man, he wrote: "No tribe could hold together if murder, robbery, or treachery were common." A tribe "superior in patriotism, fidelity, obedience, courage, sympathy, mutual aid, and readiness to sacrifice for the common good," will be naturally selected over that tribe poorer in these qualities.

But there is one supreme difference between animal and human language. Specialized though the animal call may be-as specialized as the howler's "Infant dropped from tree!"-it is never purposeful. Never does the animal cry out with the motive of enlisting aid. The cry is simply an expression of mood, and the mood catches.

The yawn, among humans, is an expression of mood comparable to animal language, and it carries the same contagious quality. I grow sleepy: I yawn. Then you yawn, and you grow sleepy. For a dramatist to write a scene in which a character yawns repeatedly would be to commit artistic suicide; the entire audience would be put to sleep. Coughing can be likewise an expression of human mood, as every actor or playwright knows An audience does not cough because the weather is bad and everyone has colds. It coughs because it is bored, and the cough is like an animal expression of wishing to be home in bed. One cougher begins his horrid work in an audience, and the cough spreads until the house is in bedlam, the actors in rage, and the play-right in retreat to the nearest saloon

For what Eliot Howard had observed throughout a life-time of bird-watching was that male birds quarrel seldom over females; what they quarrel over is real estate.

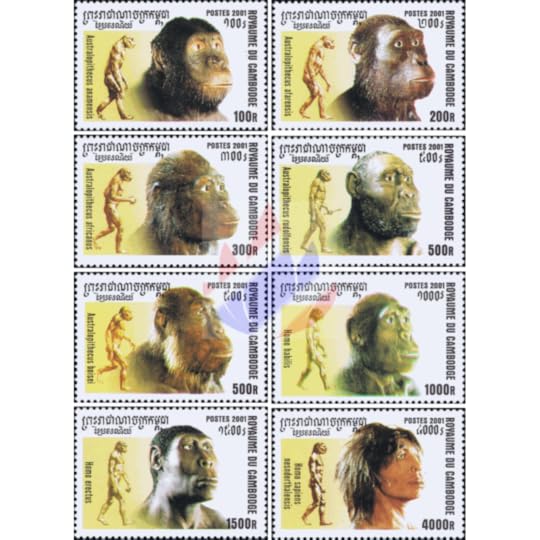

The Olduvai Gorge is the Grand Canyon of Human Evolution. With the stunning discovery there, in 1959, of the remains of the first maker of stone tools, L. S. B. Leakey established his prize preserve as the world's most important anthropological site.

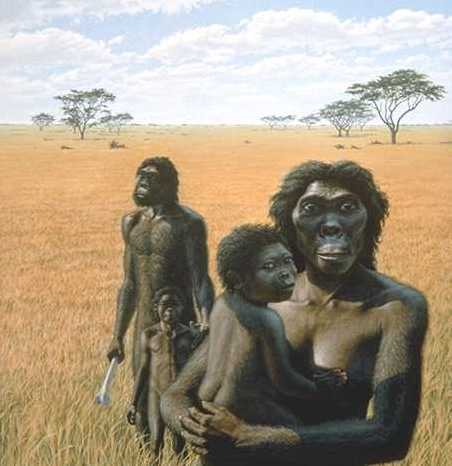

What Dart put forward in his piece was the simple thesis that Man had emerged from the anthropoid background for one reason only: because he was a killer. Long ago, perhaps many millions of years ago, a line of killer apes branched off from the non-aggressive primate background. For reasons of environmental necessity, the line adopted the predatory way. For reasons of predatory necessity the line advanced. We learned to stand erect in the first place as a necessity of the hunting life. We learned to run in our pursuit of game across the yellowing African savannah. Our hands freed for the mauling and the hauling, we had no further use for a snout; and so it retreated. And lacking fighting teeth or claws, we took recourse by necessity to the weapon. A rock, a stick, a heavy bone-to our ancestral killer ape it meant the margin of survival. But the use of the weapon meant new and multiplying demands on the nervous system for the co-ordination of muscle and touch and sight. And so at last came the enlarged brain; so at last came man. Far from the truth lay the antique assumption that man had fathered the weapon. The weapon, instead, had fathered man.

The basic fabric of modern thought is woven from one or the other of the two theories: that society is the work of man or that man is the product of society.

Oliver Goldsmith meditated that one rarely saw two male birds of a single species in a single hedge. And "one tiger to a hill" is a folk observation of equivalent discernment.

The creature whom we watch in the zoo is one denied by the conditions of his captivity the normal flow of his instinctual energies. Neither the drives of hunger nor the fear of the predator stir the idleness of his hours. Neither the commands of normal society nor the demands of territorial defence pre-empt the energies with which nature has endowed him. If he seems a creature obsessed with sex, then it is simply because sex is the only instinct for which captivity permits him an outlet.

The monkeys had been gathered from random sources in India. They survived the misfortune of a bad sea voyage on which conditions prevailed that can only be described as animal anarchy. But arriving at Santiago Island they entered what any primate must regard as a monkey Utopia. There was ample space, thirty-six acres for a few hundred individuals. No leopards haunted their nocturnal hours, or pythons their day-time excursions. There was food in abundance distributed daily and evenly by the island care-takers. Yet within one year the whole monkey community divided itself into social groups, each holding and defending a permanent territory and living in permanent hostility with its neighbours.

Birdsong takes place when and if the male gets his territory. So long as buntings are joined in flocks on the neutral feeding ground, the male never sings. Only when he finds that perch which will be the advertisement of his territorial existence his alder, his gate, his willow bough-does the will to sing enchant him.

The howling monkey distributed worse things than gloom from his home in the tree-tops. The early Spaniards, in their misery, frankly recorded all; and so a second trait became part of the howler's tradition. This was his unwholesome habit of urinating or even defecating on intruders beneath his tree.

There is an old saying that in a state of nature the object of existence is to obtain one's dinner without providing someone else with his.

I have an entirely new explanation of the so-called subconscious mind and the reason for its survival in man. I think I can prove that Freud's entire conception is based on a fabric of fallacy. No man can ever attain to anywhere near a true conception of the subconscious in man who does not know the primates under natural conditions.

"What we have to face," he said, "is that the insect is a good three hundred million years older than we are." The mammal has a history of little over a hundred million years. The insect goes back four hundred million. Evolution has had an extra three hundred million years in which to perfect the intuitions, the communications, and the social patterns of insect life. When we wonder at the societies of flattidbug or bee, we stand in the position of an infant race of superior endowment, struck with astonishment at the accomplishments of inferiors who we tend to forget are most definitely our elders.

All four factors-sex, territory, the enlarged brain and the vulnerable body— have entered into the evolution of the primate's complex society.

And yet the baboon is an evolutionary success of an outrageous order. He flourishes. He adapts himself to the most marginal conditions of climate and terrain. The bandit of Africa, he is all but ineradicable as any farmer can testify. How has he survived? The most defenceless of animals, a grounded primate, the baboon has preserved himself by developing to a high degree nature's most sophisticated instrument of defence: society.

The male lion rarely makes the kill. Such entertainments he leaves to the lioness. His normal position in a hunting pride is in the centre with lionesses spread out on either flank considerably in advance. Thus the pride will proceed into a shallow Central African valley. It is the function of the male to flush the game and drive it within range of the nearest lioness. I mentioned in another context that I did not believe the roar of the male to be like birdsong an announcement of territorial position. The devastating, brain-numbing sound seems to me rather to serve a double purpose of a different order. It terrifies the prey and focuses attention on the male, while at the same time it communicates to the silent lionesses the male's position.

While the car's occupants sit in frozen awe, the lioness on the road beside it will make use of the car as a screen between herself and her prey. We owe some of our finest lion photography not to human but lion accomplishment. The most astonishing example of adaptability of lion hunting tactics however, is found on the western margins of the Kruger reserve. In February, 1960, South African authorities began the construction of a two-hundred-mile-long fence along that margin to protect livestock and grazing on adjacent farms. Within three months lion prides learned to drive wildebeest against the fence.

It is all but inconceivable that the gorilla alone among primates has no territorial history. Perhaps he left that history behind when he came down from the trees. Or perhaps it is a more recent loss. There is evidence at Travellers Rest that some kind of territorial conflict may yet be possible granted the presence of exceptionally vital males. In 1958 two such males fought on crumbling, gullied slopes high on Mt. Muhavura. Both were giants of quarter-ton bulk. Each was of a different troop. Through bamboo thickets and higher above into clumps of lichen-covered hypericum trees just below the volcano's crater they fought for twelve days until at last one was killed.

When the naturalist one afternoon sat absorbed by a book, he received in his mouth a full beakload of minced worm and jackdaw saliva. The violence of Lorenz' rejection was now enough, one would think, to discourage the most smitten bird. It did, indeed, seem to convince the jackdaw that something had gone wrong; the mouth was the wrong place. From that time on the defensive problem became that of keeping the young jackdaw from sneaking up from behind to deposit a mushy warm tribute of love in Lorenz' ear.

The specific conclusion of zoology regarding such experiments has been that it is not the mere presence of a female but her behaviour that is the determining factor in sexual discrimination. The conservative Zuckerman while giving full credit to the danger of sweeping generalizations has stated that "it is possible that in all lower animals the attitude of the female is, in some way or other, a necessary factor in eliciting the full sexual response of the male." Whether we know it or not, such a statement juggles high-explosives as if they were Indian clubs. If it is the behaviour of the female towards a particular male that awakens his full sexual response, then we must conclude that the power of sexual choice rests largely with the female, and that sexual competition is not so much between males for the female of their choice, as between females for the male of theirs. And so the male becomes the sexual attraction, and the female in her response the sexual aggressor.

A female monkey will scramble for a bit of fruit, seize it, then discover bearing down on her the outraged dominant male to whom the food by all monkey law belongs. She will promptly present her behind to him in an effort to keep him otherwise occupied, or at least distracted, while she devours the fruit.

Whether we look to the elimination of the class struggle for the elimination of injustice, or to the abolition of nations for the abolition of war; whether we see in mother rejection the cause for human creativity, or in protein deficiency the cause for cannibals; whether we expect from poverty an explanation for crime, from lack of love an explanation for young delinquents, from city life a flowering of wickedness or from primitive simplicity a garden of goodness, the rational mind in any case views the human scene through the romantic fallacy's transparent curtain and prepares prescriptions which though quite possibly fatal to the patient may be delivered with confidence, with logic, and with the cleanest of hands.

that a man's moral worth declines in rough proportion to his distance from the soil; that civilization must be held accountable for man's noteworthy catalogue of vices; and that human fault must therefore have its origin in human institutions, relationships, and environments. The farther one moves from the sentimental premise, the more thoroughly one forgets that a premise ever existed.

Among all the brilliant founders of the American republic, Thomas Jefferson's name is the most adored today. Yet Jefferson dedicated much of his adult thought to the dubious proposition that the man of the soil possesses a soul degrees purer than the man of the city, and that a nation to remain uncorrupted must found its strength on rural rather than urban society. Whatever political forces may have shaped Jefferson's thinking, the proposition philosophically was sheer Rousseau. Out of it evolved the American myth of the honest, barefoot farmer boy; of the rugged, straight-talking backwoodsman; of cowboy innocence. Heart-warming images became part of the American memory: of Abraham Lincoln splitting rails, and Gary Cooper, infinitives. The farm became the symbol of national virtue. To this day a presidential candidate who cannot find some touch of the cowbarn to lean upon risks the solid distrust of the electorate.

We are evolutionary failures trapped between earth and a glimpse of heaven.

We have witnessed evidence that it is the females who compete for the male and that the true competition between males is for territory or status.

It is the superb paradox of our time that in a single century we have proceeded from the first iron-clad warship to the first hydrogen bomb, and from the first telegraphic communication to the beginnings of the conquest of space; yet in the understanding of our own natures, we have proceeded almost nowhere. It is an ignorance that has become institutionalized, universalized, and sanctified. It is an ignorance that transcends national or racial boundaries, and leaps happily over iron curtains as if they did not exist. Were a brotherhood of man to be formed today, then its only possible common bond would be ignorance of what man is.

Perhaps a notation in his Life provides a clue commensurate with the size of his intellect. "With me the horrid doubt always arises," he wrote in 1881, "as to whether the convictions of man's mind, which has been developed from the lower animals. are of any value or are at all trustworthy.

It is a law of nature that territorial animals whether individual or social live in eternal hostility with their territory neighbours

When Sir Arthur Keith found himself too old for any active contribution to the Second World War, his broodings produced the marvellous volume, Essays on Human Evolution, and the conclusion: "We have to recognize that the conditions that give rise to war-the separation of animals into social groups, the right' of each group to its own area, and the evolution of an enmity complex to defend such areas-were on earth long before man made his appearance."

Human warfare comes about only when the defensive instincts of a determined territorial proprietor is challenged by the predatory compulsions of an equally determined territorial Neighbour. But The command of love is as deeply buried in our nature as the commander hate.

Early in a play a dramatist will allow his audience to know that there is a gun in a drawer; and the audience will be alerted to watch for lethal things to come. I cannot fail at this moment to exhibit a gun in the drawer.

On a case stood the entire skull of a hyena. From the animal's mouth protruded the end of an antelope leg bone. It had been forced into the hyena's mouth with such thrust as to break the palate and damage the skull at the rear of the throat. The entire fossil memento of violence stood before me precisely as it had been chipped from its limestone matrix formed three-quarters of a million years ago, a quarter of a million years before the time of man.

What kept the ghosts dancing was one's daily life. Why did children play with guns? Why did boys scarcely out of their diapers cock their fingers and go bang-bang? Was it frustration? Had they all been rejected by their parents? Had they all been broken to the toilet too young? Or was it by genetic impulse?

For four generations Marais' weaver birds were denied the care of their kind, as well as any possible contact with normal weaver-bird environment. They were even fed on a synthetic diet. Then the fourth generation, when nesting time came, was given access to natural materials. Vigorously they set about plaiting nests indistinguishable from the nests in the bushveld.

One recollected the ease with which Adolf Hitler had brought about in a generation of German youth his education for death. Had he in truth induced a learned response? Or had he simply released an instinct?