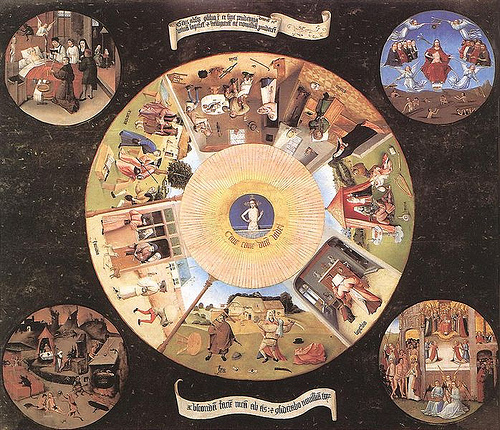

As Kalliope says below: this is a five star book for a ten star painting! Bosch is unexpected in so many ways: coming on the scene almost out of nowhere, he was a wealthy member of the social elite and belonged to one of the religious brotherhoods popular in the middle ages. His work was seemingly very popular during his lifetime--being collected by kings, numerous copies of his triptychs were made immediately, including costly tapestry cycles. Discussed and collected by kings and nobles, his style really saw few followers--maybe until the surrealists of the 20th century? Not much is really known about him and his unique style and of his work, the Garden of Earthly Delights remains an utter mystery. The narrative of the three panels doesn't function in the way we expect from Fall to Judgement to Hell. Scholars remain mainly befuddled by the work. Some have insisted that within this work are keys to secret knowledge (religious heresy) but this seems rather unlikely given how popular his work was in Spain during the height of the Inquisition. By Philip II's day, 26 out 40 extant works were held in Spain. And I have read (in another book) that Philip II was so devoted to this work of art that he requested it brought to him as he was dying.

Belting's interpretation are extremely interesting. Basically, he views the middle panel as being a version of utopia (u-chronia and u-topia). The outside wings depict the world on the third day before God created light. It is a monochrome orb surrounded by water. A Ptolemic version of the world. And yet, by Bosch's day the New World had indeed been discovered (and the picture is dated because of new world pineapples shown in the central panel). Columbus set sail to the indies but he also suspected that an earthy paradise existed in the waters antipodal of Jerusalem, as Dante described. The earthly paradise was a garden paradise outside of civilization in much the way depicted in the middle panel.

But what is Bosch trying to say? I don't think anyone knows. Belting wonders if this is not a world of "what if..." The Bible declared that all men were descended from Adam but if Columbus had only just crossed the oceans how could Adam's descendants have made it to the antipodes? This was a serious blow to the people of the time since the earthly paradise was shown to be in human imagination alone. This is a world that could have been, if there had been no sin? This is Belting's main contention.

I found it fascinating to learn that the triptych was never used in a church (it is hard to imagine it as an altar piece anyway) but was instead shown along with exotic items in the wunderkammer original owner (and probably the person who commissioned the work) Hendrick III (1483-1538) the nephew and heir of the Count of Nassau, Engelbrecht (d. 1504). Now, that is interesting! This is in the days before Kunstkammer were really even a thing--but Belting describes Durer's astonishment when visiting the castle and seeing the wild animals and all manner of exotic things from the new word and beyond. As Kalliope says:

"Belting then gives a complementary account of the Renaissance texts that dealt with Utopia, naming Sebastian Brant’s The Ship of Fools, Erasmus’s In Praise of Folly, and Thomas More’s Utopia. And although he is not proposing direct links amongst any of them he is presenting Bosch’s preoccupations in the midst of his times. Additionally, the author reminds us that this was the age of geographical discoveries in which European travel was encountering new worlds untouched by their “civilization” and was rapidly affecting the Weltanschauung of the period. Hendrick in his Wunderkammer kept this painting together with other marvels from the Outre-Mer."

I am now going to look into reading more from Belting. I am also hoping to see the Grimani Altarpiece in Venice and will definitely see the Triptych of the Temptation of St. Anthony in Lisbon after seeing the Garden of Earthy Delights in Madrid next week. Kalliope is right, El jardín de las delicias is a better name for the work.