Since I have already looked at Space Cadet, the second of Heinlein's juveniles, I’ve decided to review them all from Rocket Ship Galileo to Podkayne of Mars (I will be counting Podkayne of Mars since it was originally published as a juvenile, and I have had it recommended to me here, although apparently many, including Heinlein himself, do not count it as one of his juveniles).

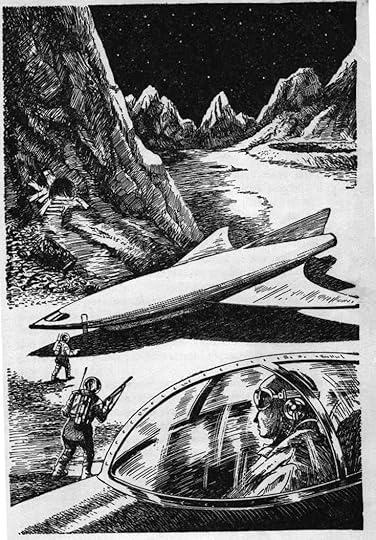

Rocket Ship Galileo tells the story of three boys who build rockets as a hobby (no date is given but I would guess it is meant to be somewhere late in the sixties since all the adult characters remember ww2 well but the boys were apparently born after it was finished). When one of their uncles, a leading Atomic Scientist, visits them they are recruited into his project to privately convert a surplus international passenger rocket into a craft capable of reaching the moon. This whole idea, of Space Travel on a shoestring budget done by a bunch of amateurs, is so ridiculous but also so appealing that I couldn’t help but be delighted. The first half of the story, where the ship his made, was a pleasure to read.

We also got some interesting worldbuilding. Heinlein always seems very interested in the politics and society that his stories are based in even if that is not the main point of the story and he has the skill of including it in the background in a way that does not feel either info-dumpy or unnatural. This is a world in which control of nuclear weapons has been given to the UN police due to a realisation after ww2 that another war would destroy mankind. Once again we see the idea of the necessary transformation of society that nuclear weapons would produce that Heinlein first discussed in Solution Unsatifactory. We get several discussians of this and the way society has changed since ww2. (By the way are this story and Space Cadet meant to be in the same universe? I know a lot of Heinlein’s stories are part of a single future history and I know that Space Cadet is part of it but I haven’t seen any confirmation of whether or not Rocket Ship Galileo is included? One could definitely imagine the Patrol of Space Cadet as a development of the UN police of this story.)

The second part of the book was where it fell apart. The division is actually pretty similar to Space Cadet with a long build up and a shorter period of adventure at the end. However, in Rocket Ship Galileo the payoff really doesn’t feel worth it. Upon landing on the moon the explorers find they have been beaten to the punch by a bunch of Nazi’s who have been secretly plotting as part of an international society ever since the end of ww2. The boys and Cargraves foil the dastardly plot of the Nazi’s and return to earth.

Now granted this was published immediately after the end of ww2 when the idea that the Nazi’s might successfully pull off some sort of international resistance might have seemed more plausible. But it all seems rather ridiculous. Also, rather disappointing. The first half of the story really emphasised the notion of the mission to the moon as a romantic quest pursued for the sake of adventure and the good of Science. I would have preferred that idea be continued on the moon but they are to busy having a rather mediocre action adventure. They also discover the remnants of a long dead civilisation on the Moon which they speculated may have destroyed itself and the Luna atmosphere in a nuclear war. Something interesting could be done with this but we are too busy fighting Nazi’s to do so.

A few passages that caught my attention.

"…The Nazis were few in number, but they represented some of the top military, scientific, and technical brains from Hitler’s crumbled empire. They had escaped from Germany, established a remote mountain base, and there had been working ever since for the redemption of the Reich. The sergeant appeared not to know where the base was; Cargraves questioned him closely. Africa? South America? An island? But all that he could get out of him was that it was a long submarine trip from Germany.

But it was the objective, der Tag, which left them too stunned to worry about their own danger. The Nazis had atom bombs, but, as long as they were still holed up in their secret base on earth, they dared not act, for the UN had them, too, and in much greater quantity.

But when they achieved space flight, they had an answer. They would sit safely out of reach on the moon and destroy the cities of earth one after another by guided missiles launched from the moon, until the completely helpless nations of earth surrendered and pleaded for mercy."

I find it interesting that this idea of the elite of the Nazi’s escaping (in a submarine no less) with various wonder weapons and secretly plotting revenge in some remote location was current so early. The idea of a secret Nazi moon base in very popular in the more paranoid recesses of the internet today. I note, however, that Antarctica, a staple of such conspiracies today, is never mentioned (neither thankfully is a hollow earth).

"As a matter of fact he was impressed. It is common enough in the United States for boys to build and take apart almost anything mechanical, from alarm clocks to hiked-up jaloppies. It is not so common for them to understand the sort of controlled and recorded experimentation on which science is based."

This is one of those lines that really makes me wonder about the way society has changed. Do modern children still fiddle around with physical technology and mechanical stuff? I don’t really think they do or at least not to the old degree. Part of it might be the fact that modern technology is such much more difficult to take apart and fiddle with even if it isn’t built to make it deliberately impossible. And part in probably just the increased control and lower tolerance for risk taking in children that exists today. I have to admit it worries me and makes me wonder about things like the great stagnation and the fact that technological advances might be slowing and why that might be. But this probably isn’t the place to discuss this and besides I’m too young to talk like this.

“…Have you any idea how much it would cost to do the research and engineering development, using the ordinary commercial methods, for anything as big as a trip to the moon?”

“No,” Art admitted. “A good many thousands, I suppose.”

Morrie spoke up. “More like a hundred thousand.”

“That’s closer. The technical director of our company made up a tentative budget of a million and a quarter.”

Behold, the optimism of pre-Space Age science fiction. That’s about 16.6 million dollars in todays money. The actual Apollo program, for the record, cost 25.4 billion dollars or over 150 billion in today’s money (estimates vary a little but they are all around that point).

Cargraves took a deep breath. “I have nothing against the Russians; if they beat me to the moon, I’ll take off my hat to them. But I prefer our system to theirs; it would be a sour day for us if it turned out that they could do something as big and as wonderful as this when we weren’t even prepared to tackle it, under our set-up. Anyhow,” he continued, “I have enough pride in my own land to want it to be us, rather than some other country.”

This book was written in 1947 when the cold was not yet clearly a thing to everyone and Heinlein has imagined a world in which the Soviet Union and the United States have worked well enough together to agree to the UN taking control of all nuclear forces and abolishing war. Only a few years later things would be a lot more tense.

“Not any place in the same county—or the next county. How would you like to be in a city when one of those things goes off?”

Ross shook his head. “I want to zig when it zags. Art, they better never have to drop another one, except in practice. If they ever start lobbing those things around, it ’ud be the end of civilization.”

“They won’t,” Art assured him. “What d’you think the UN police is for? Wars are out. Everybody knows that.”

"You know it and I know it. But I wonder if everybody knows it?”

“It’ll be just too bad if they don’t.”

"Yeah—too bad for us.”

Once again we have the idea of a sort of world international police with complete control over nuclear arms. I understand that the idea of the UN as a genuine world government was taken quite seriously in the immediate aftermath of ww2. Indeed the USA even made a proposal of surrendering its control of nuclear power to an international agency in the Baruch plan. Had that gone ahead then we might live in a world very like that envisioned by many science fiction writers and dreamers of the time. If it had actually been able to enforce its monopoly that is.

This book isn’t nearly as good as Space Cadet. Looking around it seems that this is a fairly universal opinion and it is generally thought of as the weakest of Heinlein’s juveniles. I still enjoyed the first two thirds though. A very fun concept even it is somewhat unrealistic. It has interesting worldbuilding that is a curious glimpse of attitudes in the immediate post-war period when the shock of the Atomic bomb had shaken everyone. Just a shame that it couldn’t deliver on its promise once it reached the Luna surface.