What do you think?

Rate this book

121 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published September 1, 1989

Suzanne Hoschedé (d. 1899)

And beyond the overgrown surface of the lily pond sunlight shimmered in the row of poplars, filtered through the green tent of the willow tree, shone on the open hillside, the sloping roofs and sheets hung out to dry in sunlit courtyeards. It bounced from the glass panes of the greenhouse, settled into the dust where hens pecked and strutted, drank the dark stains from the drips of wet washing and water tossed out of doors. It crept up on cool zinc milk churns, standing in shadow, and lost itself in the dark thickets of yew trees standing guard over house and garden. Indoors it fell across waxed floorboards, faded bedspreads and cushions, showing up dust in rooms where the maid had not yet been. It dried out Lily's cobweb, and turned some of the climbing roses limp on the trellis. It hummed in the wings of insects, shone on the long line of the railway track, blistered the paint of window shutters, and formed a haze, a mirage above the long gass of the pasture so that the line of trees down by the river had become dim, seemed about to dissolve in bright light, a green incandescence against the faded sky. […]There are times when I begin to wonder whether Figes may be trying a bit too hard, but to write like this in your second or third language is pretty amazing. The novella is short enough for one to read it simply as an extended prose-poem, enjoying the words for themselves, seeing the pictures that they conjure up in terms of the light and color of the Impressionist master. Figes can write this way because, important though Virginia Woolf may be, it is Claude Monet who is her ultimate truth.

Lily picked up a single petal, stroked its soft pink skin now brown at the edge, and tried blowing it into the air. It dropped on her pinafore, so she picked up a handful and tossed the whole lot into the air. She watched them fall slowly, flutter, catching the slanting light. Everything smelled fresh and damp now, as though the sun, where it came through the trees, was still cool and distant. She found beads of water caught in a curl of leaf, hanging from the tips of fern, cupped in a flower. But it was in a damp corner behind a heap of drying dead flowers and cut grass that she found the most astonishing sight of all, a cobweb strung between two posts, she hardly dared breathe for fear of disturbing it, a thousand drops of water gleaming in the tension of its fragile hold.Besides the gardener, cook, and housemaid, there are two non-family figures who may require explanation. One is the Abbé Anatole Toussaint, the parish priest, a charming character who serves as a consoler for Alice, the only ardent churchgoer among them, but also as a pleasantly non-judgmental moral reference for Claude. The other is Octave Mirbeau, journalist, art critic, salon cynic, neighbor—and fellow gardener. Monet delights in taking him on a tour of the gardens, showing him the orchids in his hothouse and the latest improvements to his beloved lily pond.

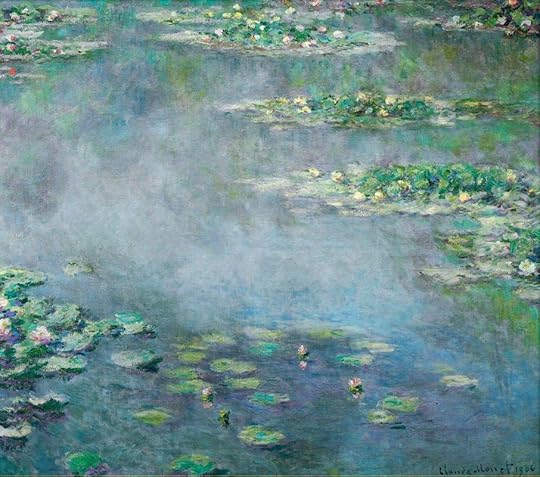

He studied the surface of the water, following the lily pads arranged like islands, an archipelago, seduced by the apparently random pattern until it was caught in the encircling clasp of the bridge, held there, like the belt round the curve of a woman's middle, or my hands, touching. Ah, I have you, he thought, smiling, all of you trapped, earth, water and sky. You thought you could escape, now that I am getting old, that you could run away, now I am slowing down, too old to track you down across wild landscapes. You did not think I could seduce you by luring you into my own back yard.Although Monet would paint many other subjects, his studies of the lily pond he built at Giverny would occupy him for the last quarter-century of his life. Figes emphasizes that this was more than a pleasant place for him to live, but a deliberate attempt to provide himself with a subject for painting that he could follow, at different times of day, and in minute variations, for years to come. She takes you with the sixty-year-old painter as he goes out in search of the pre-dawn light, puts the canvas aside as sunrise shifts the colors, takes another to capture the new effect, works for half an hour, moves on. "Monet is nothing but an eye," said Cézanne, "but my God, what an eye!" By describing everything in minute detail, Figes has us see with Monet's eyes, and amazes us with his refusal to paint anything he does not presently see through those eyes, even the memory of something he saw mere minutes ago.

Almost square, a total balance between water and sky. In still water all things are still. Cool colours only, blue fading to mist grey, smooth now, things smudging, trees fading into sky, melting in water. No dense strokes now, bright light playing off the surface of things, small, playful. I have broken through the envelope, the opaque surface of things. Odd that it should have taken so long to reach this point, knowing it, as I did, to be my element. I was blinded, dazzled by the rush of things moving, running tides, spray caught in sunlight. Looking at, not through. The bright skin of things, the shimmering envelope. But now, before the sunrise, no bright yellow to come between me and it, I look through the cool bluegrey surface to the thing itself.Later, she says, "He has to look through things now, since nothing is solid, to show how light and those things it illumines are both transubstantial, both tenuous." This idea of breaking through the envelope, of light and the things it illuminates being equally ethereal, is I think a true insight. So what does it matter that it does not describe the paintings of 1900, but the long series he began only a few years later? In Figes' tribute, her words become one with Monet's light, sharing the same miraculous dissolution of substance.

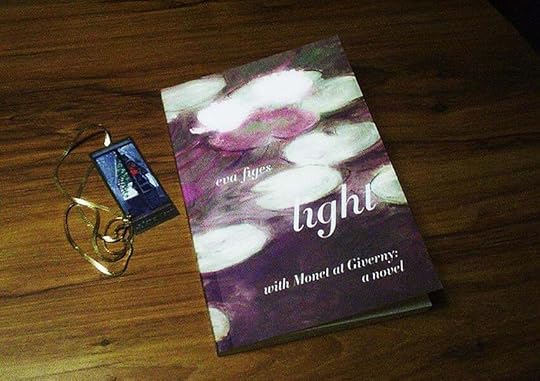

Eva Figes, 1932 — 2012

Eva Figes, 1932 — 2012 The Impressionist painting, in its most fundamental aspect, is simplicity of subject, immediacy in brush stroke, and dedicated attention to angle, intensity, and the cohesive quality of light. It's uncommon art, created by an uncommon artist, and in her novel, Light: With Monet at Giverny, English author Eva Figes also creates a similar brevity, an impressionistic sense of immediacy, and the repetition of a vital cohesive quality in an evocative and picturesque narrative. Her motif, is light.

" . . . light had begun to touch the trees, which broke into a thousand surfaces, leaves & branches throwing off light and colour. He could not look at his canvas now, because of what was happening on the river . . . Everything was always in flux, he thought, noticing a dark reddish hue close to the banks where the high trees overshadowed the water. It was both his overriding difficulty, and essential to him."

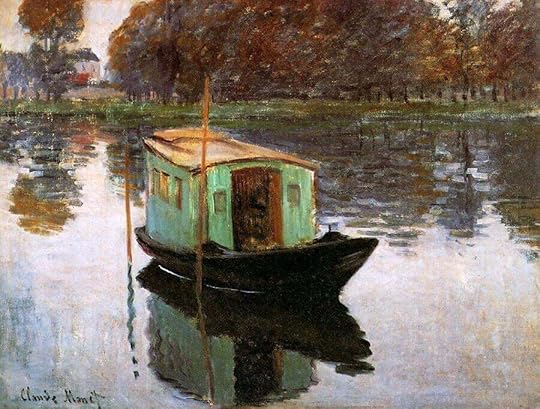

The Studio Boat (Le Bateau-atelier) by Claude Monet,1876

The Studio Boat (Le Bateau-atelier) by Claude Monet,1876 "It was not unlike what he could see for himself: each day light playing, defining, and transforming what would otherwise be merely grey amorphous matter, whether leaf, water, or rock. As with each new dawn the miracle of creation was recreated with the coming of first light."

Germaine, Lili, (far left) & Claude Monet at Giverny. (1900)

Germaine, Lili, (far left) & Claude Monet at Giverny. (1900)

"Claude had stopped at the high point of the wooden arc. He always did. When guests were taken on a tour of the garden they lingered longest here . . . the two men rested their hands on the rail & stood for a while looking down at the water, their own reflections almost immersed in the darker reflection cast by the bridge itself , so that only their heads were outlined in the light of shining water."

Thank you Hannah