What do you think?

Rate this book

Hardcover

First published November 3, 2008

A pithy introduction before I begin my review. First, about me: I love philosophy, I love political theory. These are my obsessions. When it comes to reading, I prefer the prose of writers such as, John Stuart Mill, David Hume, and Bertrand Russell(you really must read Free Man's Worship; who would ever of thought Russell was such a hopeless existentialist?). If I am in an acutely inquisitive mood, I appreciate reading John Rawls, Michel Foucault, Friedrich Nietzsche, and my personal favorite, Martin Heidegger.

I had just finished re-reading Mill’s On Liberty, after abridging a particularly extended sequence of a book after book of political thought when I decided that I must return again to the beginning. You see, as part of this cycle, I had recently read Allan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, and I couldn’t figure out for the life of me why so many “conservative” thinkers had affirmed this book as some kind of call to action. To me, the musings of Bloom seemed antithetical and borderline inconsistent. In one position he seems to be advocating some kind of inherent right to prejudice, whilst simultaneously calling for critical thinking. I just could not seem to get passed his deep-seated psychological projectionism, and his penchant for elitist poppycock. I thought perhaps I had misread some of the works that Bloom mentioned and I took it to heart. I would now go back and find the best translations (which, awkwardly, by the way, I do think Bloom’s translation of The Republic to be of the finest quality I had ever read), of some of the “Classics”.

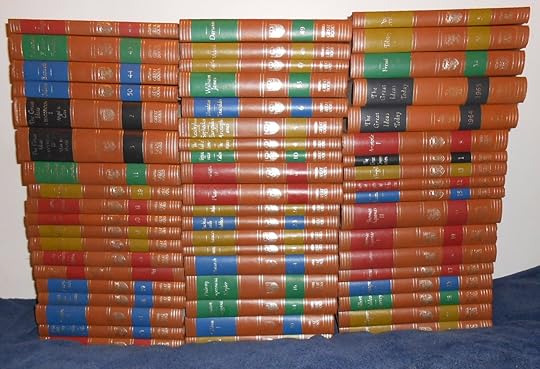

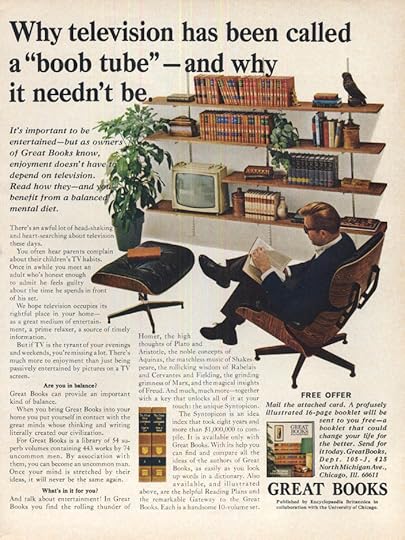

While I was probing the local library shelves for a good translation of Homer’s Iliad 1 I happened upon this book. Whatever system of cataloging the library was using, Alex Beam’s A Great Idea at the Time: The Rise, Fall, and Curious Afterlife of the Great Books found itself shelved right alongside the likes of Homer and Virgil. I read the dust jacket preview and decided to give it reading. Thus begins the review.

As mentioned earlier, I have spent the better half of the last six months gradually working my way through some of the more intricate political texts, and arguments, ever; at least in my opinion. Hence, the first impression I got from the introduction, and chapter one, was that this book is exceptionally readable. That makes a difference. It was almost like the disparity between work and play. While the past six months have been work, the straightforwardness of the prose used by Beam was like a vacation. This is a compliment and not a sleight. When reading through extremely challenging texts, there is always the quandary of translation apropos verbiage used during that historic period. What Beam has done is poised the readability of this work, and structured it into a coherent whole. Instead of the usual 20 – 30 pages of reading, followed by a decompression period of thinking about what was written, one can easily tackle this book in one sitting.

It is observable throughout the text that Beam is knowledgeable of not only his subject matter but, the gentle art of presenting the “story” without too much bias. To some this may seem erroneous – I have read some of the other reviews; or, should they be called critiques? Needless to say, if you were to read the “Acknowledgments,” and “Notes on Sources,” it could be easily deduced that Beam has done his investigative homework.

Another thought that came to me throughout the reading, was that this is one of the few books – outside the Classical texts – and obvious expositions by the likes of Philosopher’s viz., Edmund Husserl, Hegel, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty – where I have seen an actual discussion of important words and their meaning. Here I am referring to words like ousia [οὐσία] and arête [ἀρετή]. These words embrace concepts difficult to translate into English and I was happy to read the attempts by Beam to do such. Beam is absolutely correct in his exposition of students that study ancient texts and ideas. I can attest (is this anecdotal evidence?) that it is hard to find anyone, outside the Ivory Towers of academia, who are willing to discuss concepts such as Being, Geist [spirit?], Despair, and my favorite quote of all time: “Das Nichts Selbst Nichtet”. Yet, these very “ideas” permeate the core of humanity.

Ultimately, I would like to thank Alex Beam for providing a tiny interruption to my progress (or is it really?) of attempting to understand the great thinkers of history. I have culled many ideas from reading this book, and I hope that when a critical reflection is done by others who read it, they will also see some usefulness in the pages.

Lastly, I would not worry very much about the “star” rating. It is very rare for me to give any book five stars. Nonetheless, this book is a solid three and that means I enjoyed it for the recreational value. Now, it is back to finishing off some reading by Gerald A. Cohen on his critique of Rawls in Rescuing Justice and Equality. Who knows, perhaps one day, hundreds of years from now, someone will be reading Cohen as a great of the ancient thinkers?