The first two pieces, the discovery of the Pacific Ocean and the fall of Bysantium, had me bewitched. I read the first in line to embark a plane and the second on a beach in my beloved Sicily, both right after a grueling exam session, so part of my enthusiasm might be due to the fact that it had been way too long since I had taken a couple of hours just to read a book that had nothing to do with school. But I found both these accounts extremely moving and skillfully told. What caught me was not just the form, the style, but rather the content, and the rightness I felt in the choice, on Zweig's part, of these two moments as "stellar hours" of human history.

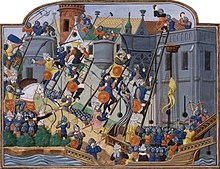

Actually, in all honesty, the choice of the discovery of the Pacific ocean baffled me a little at first. I believe I had subconsciously interpreted the title as moments when men's decisions were critical in the shaping of the course of history. My guess is this happened because I read the book in Italian, and the Italian title reads Momenti fatali, meaning moments ruled by fate and/or decisive for the future, as the English title recites. The overlapping of these two meanings in Italian had me think this collection would include accounts of events where things could have gone very very differently, had it not been for one silly twist of fate or one single decision (or lack thereof) of a single man. And in some cases, this supposition of mine proved to be right, as in the Waterloo story about Grouchy's indecisiveness, or the Bysantium story and the Kerkaporta inexplicably left unprotected. But the discovery of the Pacific baffled me, as I said. It would have been discovered, sooner or later, wouldn't it? Why was it fatale, fateful? And then I worked it out in my head: it wasn't the moments per se, but rather the men who carried these moments out.

I find it interesting that Zweig cites no historical sources whatsoever. This apparent lack of bibliography is what might be argued to place Decisive Moments in the realm of metahistory. How do we know how Balboa felt when he lay his eyes, first of the Westerners, on the Pacific ocean? Zweig reconstructs precisely this, the mind of the man. In doing so, however, in presenting historical moments in such a fictionalized and subjectivistic mode, he also gives way to his own personal bias. The result is often an overly-dramatic and excessively romanticized account where spontaneous genius rules true art, ambition can't lead but to ruin, and it's amoral to admire cunning but ruthless men. (The utter absence of women is another problem altogether, but we'll let it pass since the book dates back to 90 years ago.)

The collection also includes portraits of various artists (Handel, Goethe, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy) and I think these are the weakest pieces of the volume. I profoundly disagree with Zweig's Sainte-Beuverian view of arts, meaning I cannot relate to his account on the composition of Goethe's Marienbad Elegy, even though the core facts are of course true. Toltoy's piece was certainly creative, formally speaking, but so cloying, so partial on telling instead of showing (and I won't accept the theatrical form as a justification for this) that I couldn't help skipping a couple of paragraphs just out of self-preservation.

My conclusion is that I expected something different from what I actually got, and that might have distorted my perceptions a bit, but on the other hand, my tastes, especially stylistically and also ideologically (my preference here is for neutrality), run in a completely different direction than what Zweig presented the reader with in his Decisive Moments. Conceptually, this is a wonderful collection, but I'll grant myself the right to disagree on the modes of its realization.