What do you think?

Rate this book

Paperback

First published January 1, 1889

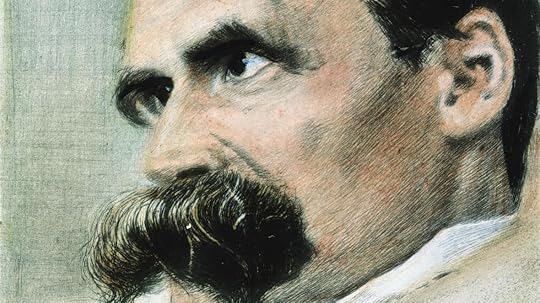

Mainly, I think, my praise for Nietzsche lies in the fact that he debunked the long-standing European (or Western, you can say) myth of supremacy, of its damn superiority. Well into the nineteenth century can be found these "seeds" of self-confidence in all those nations, where that tattoo of Christianity beat ever higher, as came time.

-Our age is proud of its historical sense: how was it able to make itself believe in the nonsensical notion that the crude miracle-worker and redeemer fable comes at the commencement of Christianity- and that everything spiritual and symbolic is only a subsequent development? The main thing is, Nietzsche not only slams every such nation for its unruly attachment to that religion, but he also investigates other such beliefs and religions over the world. There is a detailed dissertation on the boons of Buddhism, there is an affirmation of the Indian caste system over the thenEuropean society, there is eulogium for Islamism, and for Greeks there is only contempt, for Romans there is pity, for Germans there is disgust, for the French he has the highest loathing...Here is one philosopher who knew how to state a point, who knew how to convince his audiences, and who, finally, knew a great deal about research. No empty thinking has any space here.

And it could go on forever like this. But there are several paragraphs that sparkle and bristle with heavy content, with insightful thoughts, that are by no means irrational. His propositions on the birth of art, on the needs and stimuli to art,- they are true, thought-provoking, rational and original. Will I forget them? Most likely not. 'All art stems from intoxication!'- ha, that looks correct, I'll wager.

The point is, Nietzsche is obviously more relevant today than he was a century ago. You've heard of Twitter beefs, online ranting,- but if you haven't, in that sense, ever heard of Nietzsche, you're missing something big-time. When the sub-title says 'How to Philosophize with a Hammer', you've got to take it literally. There is also devoted a short section to what I hold to be the very essence of existentialism, ('No one is accountable for existing at all, or for being constituted as he is, or for living in the circumstances and surroundings in which he lives), and even though I wondered what he had to say on Kierkegaard, this was more than delightful.