What do you think?

Rate this book

Hardcover

First published January 1, 1959

Joyce and another student, George Clancy, liked to rouse Cadic [teacher] to flights of miscomprehension. In a favourite little drama, Joyce would snicker offensively at Clancy's efforts to translate a page into English. Clancy pretended to be furious and demanded an apology, which Joyce refused. Then Clancy would challenge Joyce to a duel in the Phoenix Park. The horrified Cadic would rush in to conciliate the fiery Celts, and after much horseplay would persuade them to shake hands.

When Yeats imprudently mentioned the names of Balzac and of Swinburne, Joyce burst out laughing so that everyone in the cafe turned round to look at him. 'Who reads Balzac today?' he exclaimed.

Jim is beginning his novel, as he usually begins things, half in anger [...] I suggested the title of the paper 'A Portrait of the Artist', and this evening, sitting in the kitchen, Jim told me his idea for the novel. It is to be almost autobiographical, and naturally as it comes from Jim, satirical.

The couple went on to London. As yet neither wholly trusted the other. When they arrived in the city, Joyce left Nora for two hours in a park while he went to see Arthur Symons. She thought he would not return. But he did, and he was to surprise his friends, and perhaps himself too, by his future constancy. As for Nora, she was steadfast for the rest of her life.

Copy No. 1000 [of Ulysses] he inscribed to his wife and presented to her in Arthur Power's presence. Here, in Ithaca, was Penelope. Nora at once offered to sell it to Power. Joyce smiled but was not pleased. He kept urging her to read the book, yet she would not.

he could answer truthfully, 'It's hard to say.' 'Then what is the title of it?' asked Suter. This time Joyce was less candid: 'I don't know. It is like a mountain that I tunnel into from every direction, but I don't know what I will find.' Actually he did know the title at least, and had told it to Nora in strictest secrecy. It was to be 'Finnegans Wake', the apostrophe omitted because it meant both the death of Finnegan and the resurgence of all Finnegans. The title came from the ballad about the hod-carrier who falls from a ladder to what is assumed to be his death, but is revived by the smell of the whiskey at his wake.

One such evening ended with Joyce alighting from the taxi at his door and suddenly plunging up the street shouting, 'I made them take it,' presumably an angry brag that he had foisted 'Ulysses' upon the public. Nora looked at Laubenstein and said, 'Never mind, I'll handle him,' and soon deftly collected her fugitive.

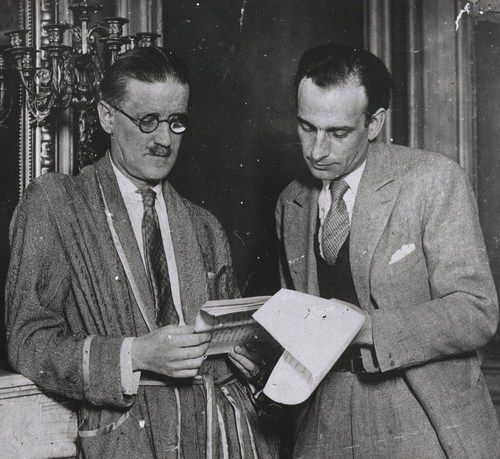

in the middle of one such session there was a knock at the door which Beckett didn't hear. Joyce said, 'Come in,' and Beckett wrote it down. Afterwards he read back what he had written and Joyce said, 'What's that "Come in"?' 'Yes, you said that,' said Beckett. Joyce thought for a moment, then said, 'Let it stand.' He was quite willing to accept coincidence as his collaborator.

The surface of the life Joyce lived seemed always erratic and provisional. But its central meaning was directed as consciously as his work. The ingenuity with which he wrote his books was the same with which he forced the world to read them; the smiling affection he extended to Bloom and his other principal characters was the same that he gave to the members of his family; his disregard for bourgeois thrift and convention "was the splendid extravagance which enabled him in literature to make an intractable wilderness into a new state. In whatever he did, his two profound interests-his family and his writings-kept their place. These passions never dwindled. The intensity of the first gave his work its sympathy and humanity; the intensity of the second raised his life to dignity and high dedication.