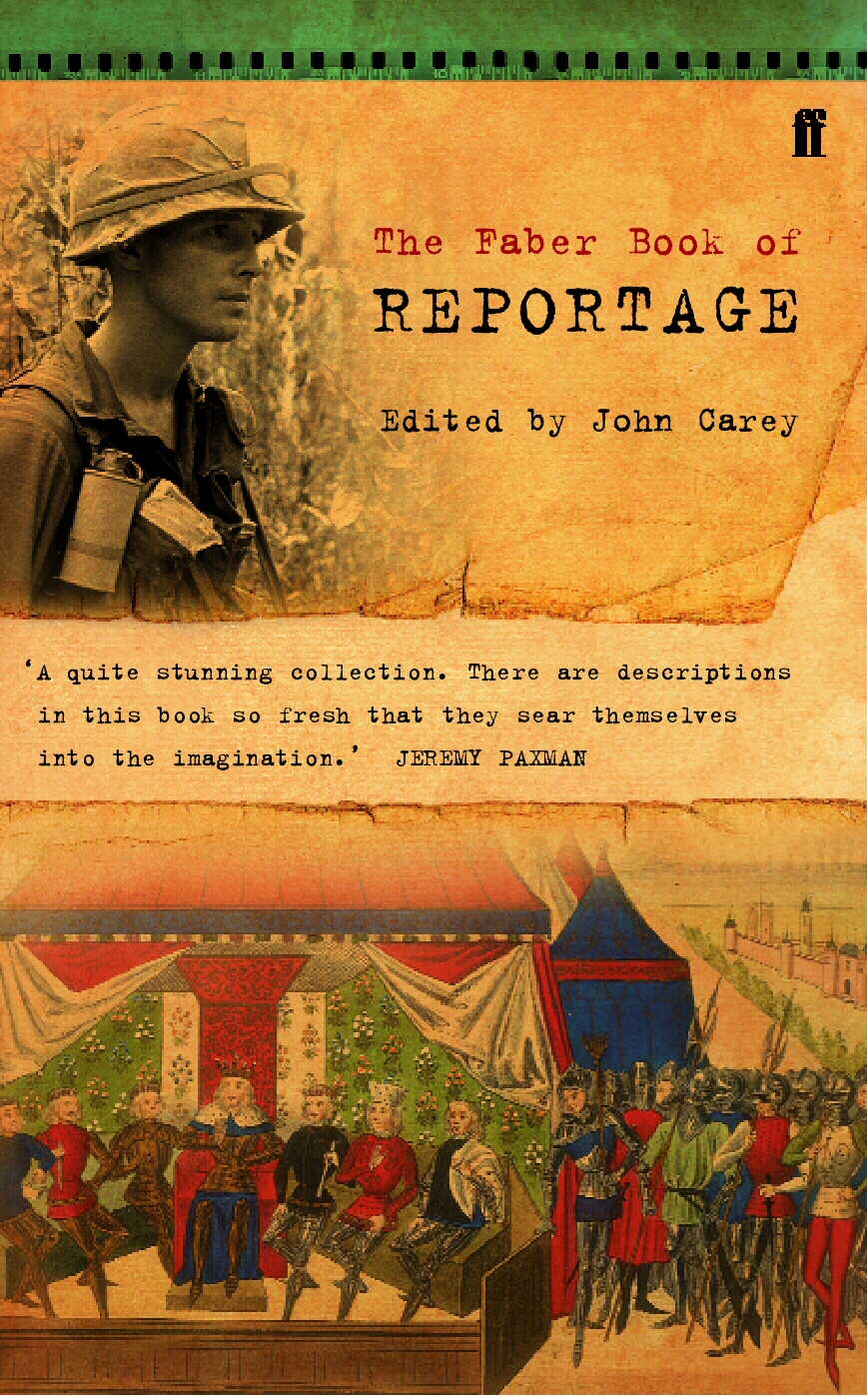

Looking at the other editions, this book seems to have also been published under the title Eyewitness to History. It is, as the title(s) suggest(s), a collection of first-hand reports. Most are only a few pages long, and as they are all self-contained, the book is one that you can pick up and set down as you please. It’s not a bad book to have around if you have 10 minutes to spare - you can usually read a couple of the entries in that time. In total it’s a pretty hefty tome. I read the Kindle edition which at the time of writing isn’t listed on GR. Whilst the paperback version is described here as having 686 pages, my Kindle version ran to 1,062 pages, not including the list of sources and the index. The book was published in 1987, which unfortunately means it doesn’t contain reports from the momentous year of 1989. It opens with Thucydides’ description of a plague in Athens in 430BC and closes with an account of the fall of President Marcos of The Philippines in 1986.

Despite those opening and closing chapters, you can tell that this is a book published in Britain, with a British editor. The reports include a disproportionate number of incidents that either occur in Britain or at least involve British people in other countries. There will always be disagreement over the selection of material for a collection like this, but in my opinion there’s also an over-concentration on descriptions of wartime events. WW2 takes up an enormous section, but many other wars are included as well. Lastly, and possibly as a consequence of the emphasis on WW2, almost half the statements in the book are taken from the 20th century.

There were probably about a dozen or so of the accounts which I had read before.

There are so many accounts in here it is difficult to pick out individual examples. I was astonished to read a letter from Oliver Cromwell to his brother-in-law after the Battle of Marston Moor in 1644. He starts by speaking of how the Parliamentarians had won a glorious victory, thanks to be God etc. In the middle of the letter he suddenly, and with no preamble, says “Sir, God hath taken away your eldest son by a cannon-shot. It brake his leg. We were necessitated to have it cut off, whereof he died”. That was that!

There’s a great deal of tragedy described. I found one of the most affecting to be the death of an 8-year-old chimney sweep in 1813, burned and suffocated after being sent down a still-hot chimney, into which he got stuck.

A piece from Robert Graves, from 1915, described the incredible courage of a “tender-hearted lance-corporal named Baxter”, who walked out on his own into No-Man’s Land on the Western Front, waving a handkerchief, to go to a wounded soldier trapped close to the German lines. Initially the Germans fired at him but eventually they let him come on. Graves recommended Baxter for the Victoria Cross, but “the authorities thought it worth no more than a Distinguished Conduct Medal.”

Lighter events included a description of the “frost fairs” held on the frozen River Thames during the 17th century, and an account of near-farcical events during the funeral of King George II in 1760, an interesting contrast to the precision of the military manoeuvres during the recent funeral of Elizabeth II.

I can’t imagine the amount of research that would have been required to put this collection together.