What do you think?

Rate this book

720 pages, Hardcover

First published September 11, 2012

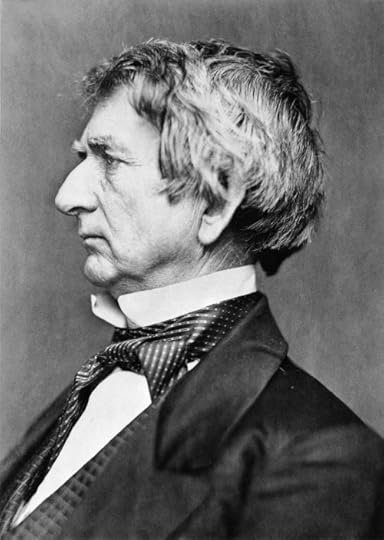

As [Seward] put it in his memoir, “politics was the important and engrossing business of the country.” Many observers agreed. Alexis de Tocqueville, the Frenchman who toured the United States in the early 1830s, observed that it was hard to overstate the importance of politics for Americans: “If an American were condemned to confine his activity to his own affairs, he would be robbed of one half of his existence; he would feel an immense void in the life which he is accustomed to lead, and his wretchedness would be unbearable.”

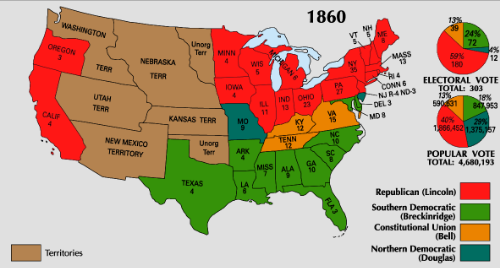

Dr. Tullio Verdi, the Washington physician who frequently attended the Seward family, recalled that he asked Seward during the war how he had failed to secure the nomination that had seemed so certain. Seward replied that “the leader of a political party in a country like ours is so exposed that his enemies become as numerous and formidable as his friends, and in an election you must put forward the man who will carry the highest number of votes. Pennsylvania would not have voted for me, and without her vote we could not carry the election; hence I was not an available man. Mr. Lincoln possessed all the necessary qualifications to represent our party, and being comparatively unknown, had not to contend with the animosities generally marshaled against a leader. We made him the candidate; he was elected, and we have never had reason to regret it.”

Seward was worried that the Radical [Republican] approach could lead to a second civil war. He was willing to leave the treatment of southern blacks to the southern state governments, in the same way that the treatment of northern blacks was handled by the northern state governments. Seward no longer had a Radical in his own household, in the form of his wife Frances, who would surely have shared the Radical concern for the fate of southern blacks. Unlike Frances, Seward was never an abolitionist who insisted on the immediate end of slavery; he was prepared before the Civil War to wait for decades to see the gradual but inevitable end of the slave system. It is thus not surprising that after the war and his wife’s death, he was prepared to wait for gradual social and political processes to improve the lives of former slaves and their descendants.

In sum, although Seward was far from perfect, his talents and accomplishments more than entitle him to be called a statesman. Indeed, other than presidents, Seward was the foremost American statesman of the nineteenth century.