What do you think?

Rate this book

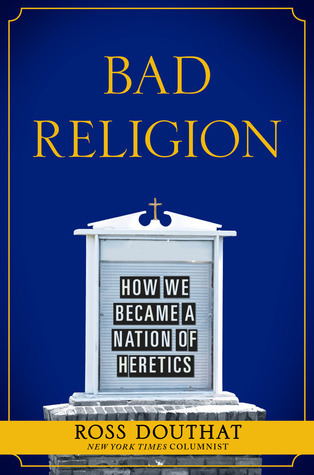

352 pages, Paperback

First published April 17, 2012

"America's problem isn't too much religion, or too little of it. It's bad religion: the slow-motion collapse of traditional Christianity and the rise of a variety of destructive pseudo-Christianities in its place. Since the 1960’s, the institutions that sustained orthodox Christian belief – Catholic and Protestant alike – have entered a state of near-terminal decline." (page 3)