What do you think?

Rate this book

696 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2006

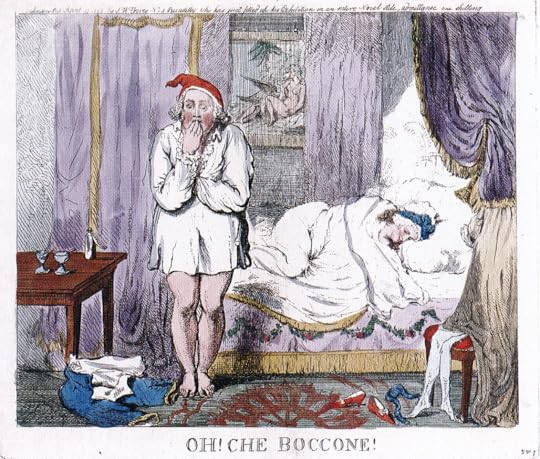

How did women bear the many condescending, cruel, parodic or fantasy-laden representations of themselves that were peddled by men? What did they think of men's farts-and-bums humour when (or if) they met it? And did they recognize ‘misogyny’ when it hit them? […] by modern standards practically the whole body of jokes and satires that addressed relations between the sexes can seem to have been woman-fearing, woman-hating or woman-patronizing. […] Add to that our tendency to project on to past women present-day notion of what they should have found intolerable, and the trickiness of the task is clear. What women laughed at, how unrestrainedly they laughed, whether they laughed at all, and how many of them laughed, are among the murkiest of our subjects.

We […] can hardly regret the softening of the manners that once sustained blatant masculinism, sensuality and malice, any more than we could wish for the return of public executions. […] A good deal of the old satire now seems infantile, fart-obsessed and gross, and as cynical and cruel as the hierarchical society that hatched it. [… But] what sustained the cleansing process was a deepening wish to control, moralize and pathologize those who defied that process, along with that mounting fastidiousness about aggression, desire and the body that now helps to define moral respectability.