What an incredible (true!) story. That being said, I would warn any readers that the first few sections on the history of the San peoples (van der Post uses Bushmen) is incredibly stark and depressing. If I had not been sure he would find the people he sought, I would have given up there and then, despite his ability to render horrible scenes into beautiful prose. Spoiler alert: van der Post did find what he sought and more and once you get there, you will know it was well worth the trip. I only wish he had spent as much time there as at the journey to get there.

Quotes that caught my eye

‘Old tannie sea-cow’ was our endearing way of naming the hippopotamus, so called because it was there in the surf of the sea to welcome my people when they first landed in Africa. (18)

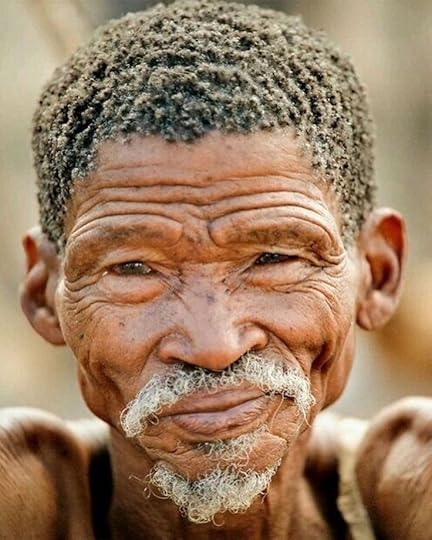

What drew me so strongly to the Bushman was that he appeared to belong to my native land as no other human being has ever belonged. Wherever he went he contained, and was contained, deeply within the symmetry of the land. His spirit was naturally symmetrical because moving in the stream of the instinctive certainty of belonging he remained within his faithful proportions. (22)

… it is enough to stress here how mistaken is the common assumption that literature exist only where there is a system of writing. Literature, surely, exists wherever the living word is spoken. (29)

…these and many more of what the Bushmanb called not beasts, birds, and insects but ‘persons of the early race’,… (31)

…what sort of a person is the Bushman? His paintings show him clearly to be illuminated with spirit; the lamp may have been antique but the oil is authentic and timeless, and the flame was well and tenderly lit. indeed, his capacity for love shows up like fire on a hill at night. He alone of all the races of Africa, was so much of its earth and innermost being that he tried constantly to glorify it by adorning its stones and decorating its rocks with painting. We other races went through Africa like locusts, devouring and stripping the land for what we could get out of it. the Bushman was there solely because he belonged to it. Accordingly he endeavoured in many ways to express this feeling of belonging, which is love, but the greatest of them was in the manner of his painting. (32)

…the ancient law of human nature holds goo. First one must vilify in one’s own spirit what one is about to destroy in other; and the greater the unadmitted doubt of the deed within, the greater the fanaticism of the action without. (41)

Almost every tribe of Africa picked up only what was negative in the situation. The weak lost the courage and wit that alone might have saved them and were ruled by blind terror. But they, too, whenever forced to flee into the country of someone even weaker than themselves, practiced with all the ruthlessness of the convert the terror which had hitherto flayed them. The strong thought of little more than plundering and preying on the weak and making themselves ever stronger. Then they fell out among themselves. Setting up rival combinations for loot and destruction. (49)

All along the extremities of the zone of terror packs of lesser tyrants and robbers formed and reformed like hyaenas and jackals to quarrel over what was left by the pride of lions. Pushed out of the Cape by the fast-expanding European colony, the Hottentots, bands of bastards, and outlaws of all sorts of colours armed with European guns, moved in north to pick off whatever was left of life on the smoking and reeling veld. Away from the main routes of the murderous traffic there was no secluded place that did not conceal some group of broken people clutching at life like drowning men at straws. Food had become so scare that far and wide the outcasts and survivors of disrupted tribes began to eat one another without shame. For two generations and more a phase of intensive cannibalism set in over all the unfamiliar parts of the land. Too weak and unequipped to hunt the, by now, thoroughly alarmed and athletic game of the veld, men made up packs to hunt, snare, trap, kill, and eat other weaker men. Even the lions and leopards, it is said, gave up pr4eying on game and indulged in a new and easier taste for the flesh of defenceless humans. When a whiff of human being came to their noses the terrible wild-dogs broke off the hard chase of buck and, moaning with relish, went after some emaciated fugitive, while vultures became so gorged that they could scarce waddle fast enough to take to the air. (50-51)

Even in my childhood great quantities of bone, then almost entirely animal were still a feature of the landscape. I still remember how the precise wind of our blue transparent winters would sing a lyric of fate in the hollow bone left on the veld and how I shivered in my imagination. (52)

Then, with some little barter fair enogh perhaps according to the tight rule of the narrow day, a great deal of legal guile, natueral cunning, bribery, and corruption, al enoucraged by supplies of the fiery Cape brandy known to us children as ‘Blitz’ or ‘Lightning’, they dispossessed the dispossessing Griquas. (54)

…making the blue of the uplands more blue, the empty plains more desolate, and adding to the voice of the wind as it climbed over the hilltops and streaked down lean towards the river, the wail of the rejected aboriginal spirit crying to be re-born. (60)

I had to live not only my own life but also the life of my time. (61)

I alternated between Africa and Europe in a state of suspended being like a ghost from some unquiet grave, shocked almost as much by the ruthlessness and brutalities of peace as I had been by those of war, deeply aware only of how privileged I was in being, even so uneasily, alive. (63)

Human society and living beings, it seemed to me, ought to be excluded from so clam and rational a view. The whole of human development, far from having been a product of steady evolution, seemed subject to only partially explicable and almost invariably violent mutations. Entire cultures and groups of individuals appeared imprisoned for centuries in a static shape which they endured with log-suffering indifference, and then suddenly, for on demonstrable cause, became susceptible to drastic changes and wild surges of development. It was as if the movement of life throughout the ages was not a Darwinian caterpillar but a startled kangaroo, going out towards the future in a series of unpredictable hops, stops, skips, and bounds. Indeed when I came to study physics I had a feeling that the modern concept of energy could perhaps throw more light on the process than any of the more conventional approaches to the subject. It seemed that specie, society, and individuals behaved more like thunder-clouds than scrubbed, neatly clothed, and well-behaved children of reason. Throughout the ages life appeared to build up great invisible charges like clouds and earth of electricity, until suddenly in a sultry hour the spirit moved, the wind rose, a drop of rain fell acid in the dust, fire flared in the nerve, and drums rolled to produce what we call thunder and lightning in the heavens, and chance and change in human society and personality. (69-70)

“If you must point in that direction, please be so good as to refrain from doing it so rudely with your finger straight out like that, but instead, politely, only with the knuckle of your thumb, the tip turned down towards your hand thus. … Otherwise you’ll send away the rain we’ll be needing soon.” (102)

When the aircraft had come and gone we went to this official’s house on the river, where we sat on the veranda among a vast though oddly-ordered chaos of books, magazines, fishing-rods, spoons and flies, and all the paraphernalia that had helped him travel the long years, alone, without injury to his spirit. (124)

Almost at our feet, the great Okovango river broke into splinters on the pointed papyrus mat at the door of the swamps. (125)

As we went deeper into the interior the crocodile seemed to grow bigger, sleeker, and less alert. They were sleeping in the sun on every spit of earth that protruded beyond the cool papyrus shadows. We would be upon them before they were aware of us and then, instantly, they took straight to the water like bronze swords to their sheaths. One, surprised on a sandy shallow, gave the ground a resounding smack with his tail, hurled himself high in the air, and looped a gleaming prehistoric loop straight into the deepest water. Round another bend we sailed into the midst of a feud between two desperate males. They rose half out of the water. Their small forefeet sparring like dachshund puppies, but their long jaws snapping and grappling with incredible rapidity. They went under still wrestling, the tips of their tails agitating the water just beneath the surface like a shoal of eels.

At that distance, to me, one clump of trees and feather of palm was very much like another. To our guide, however, each group was different and he proceeded to read them like separate words forming a sentence in a well-thumbed book. (136)

That incident over, Samutchoso went into a hut and emerged almost at once with a stick and a small bundle in hand. He spoke a few words to the women and children and again there were no explanations questions, or protests. On the faces of all was an expression of the acceptance of people accustomed to converting change and change into the currency of fate. (180)

After so many weeks in flat land and level swamp the sudden lift of the remote hills produced an immediate emotion and one experienced forthwith that urge to devotion which once made hills and mountains scared to man who then believed that wherever the earth soared upwards to meet the sky one was in the presence of an act of the spirit as much as a feature of geology. I thought of the psalmist’s ‘I will uplift my eyes until the hills from whence cometh my help,’ and marvelled that the same instinct had conducted Samutchoso to the hills to pray. (181)

The hills were in sole command and so dominated our impressions that the two Land-Rovers, their behinds wiggling and waggling over the rough roadless plain as they searched for camping site and water, seemed like puppies fawning towards the feet of a stern master. (183)

An hour later the others broke out of the bush almost on top of us. We had had no warning of their coming for the air was so thin and stricken with heat that it had not life enough to carry sound. (183)

Daily, I became more convinced that in this regard our version of history was largely rationalization and justification of our own lack of scruple and excess of greed, and that the models drawn upon by historians and artists must have been the Bushmen nearest them who had already been wrenched out of their own authentic pattern to become debased by insecurity and degraded by helplessness against our well-armed selfishness. (215)

It was most impressive to see them skin and cut up game. Nothing was wasted or discarded except the gall and dung in the stomach. The entrails were cleaned and preserved, and even the half-digested grasses in the paunch were wrong out like washing for the juices they contained, and these collected in the skin and drunk by the hunters to save their precious water. (216)

This they did out of a deadly compound of a mysterious grub found in summer at the end-root of a certain desert bush, powdered cobra poison, and a gum produced by chewing a special aloe blade in the mouth and then mixing the extract in a wooden cup with the other powders. (218)

Words/phrases that I couldn’t find anywhere

Chinese Vlakte: There is a great plain between blue hills in south Africa called to this day the ‘Chinese Vlakte’ after the Bushman hunters who once inhabited it. (14)

Krans: It is astonishing how in this late hour, they burn within the aubergine shadows of cave and overhang of cliff and krans,… (30)

Mountains of the Night: In the Mountains of the Night hard by the Great River, paintings of an enemy in red coats and riflemen on horses are briefly seen. (32)

Clarification, I think, of the two different tribes’ he lists: Tambuki and Tembu. From what I can find the names should be or are now Tamboekie and Thembu, and are actually two different names for the same Xhosa-speaking people.

‘… to burn and loot Africa from the Indian Ocean to the Zambesi, and from the Umbeni to the Great Lakes.’ (50) Is the Umbeni the river Umgeni?

“Massarwa! Bushman!’ (64) Might it be a title of some sort?

An internet search suggests that only van der Post uses this proper noun (in other books in addition to this one): “He was a man of the Bamangkwetsi,…” (91)

Is van der Post’s Shinamba Hills the same as the Shimba Hills in Kenya? ‘As a result the next day we held on south until we came to the first of the blue Shinmba Hills.’ (110)

‘…and between us and them lay a bush of shimmering peacock leaves.’ (181) I wonder what plant this is… there is something called a peacock plant but it is native to Brazil….

I can’t find evidence of either of these two places: ‘…the heart of the desert contained between what must once have been the mighty water-courses of the Bhuitsivango and Okwa.’ (202)

‘And, of course, they loved the wild tsamma melon in all forms, and highly prized the eland cucumber.’ (217) Okay, I know what an eland is and cucumber is easy but what is this?

‘The shuttle-cock was made of a single wing-tip feather of the giant bustard tied to a long leather lash and fastened to the heavy and area marayamma nut.’ (220) So what’s a marayamma nut?