What do you think?

Rate this book

584 pages, Hardcover

First published September 12, 2011

...the brushwork is so broad, the definition of forms so unsure, that the painter seems to have fallen prey to some form of essential tremor, an uncontrollable shaking of the hands, as well as perhaps to damage of the eyes.Caravaggio's reputation as an accomplished painter enabled him to win prestigious and well-paid commissions at all the places he visited after fleeing Malta even though he was a fugitive and probably knew that he was being tracked by Maltese agents.

St John the Baptist by CaravaggioThe following excerpt is what this book had to say about the above painting. I have included it here so I can review it prior to my next visit to the museum.

(Nelson Atkins Museum of Art)

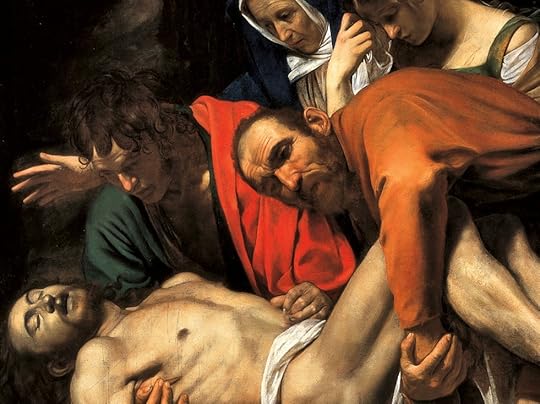

It was probably in the summer of 1604, between fights, that Caravaggio painted the hauntingly intense St John the Baptist now in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Kansas City. The picture was almost certainly painted for the Genoese banker Ottavio Costa. There is an early copy in the church of the Oratory of the Confraternity of Conscente, in Liguria, which was a fief of the Costa dynasty. The family had paid for the building of the church, so it may be that Caravaggio's painting was originally destined for its high altar, and subsequently replaced by the copy for reasons unknown. Perhaps Ottavio Costa was so impressed by the work when he saw it that he decided to keep it for his art collection in Rome.The following excerpt from the book tells of one occasion when Caravaggio's work was rejected because it portrayed St Matthew with too much appearance of a poor peasant instead of an important saint of the church. I happen to be sympathetic with Caravaggio's preference to show the followers of Jesus as being plain and poor folk.

The picture is very different to the St John the Baptist painted for Ciriaco Mattei a couple of years before. As in the earlier painting, the saint occupies an unusually lush desert wilderness. Dock leaves grow in profusion at his feet. But he is no longer an ecstatic, laughing boy. He has become a melancholy adolescent, glowering in his solitude. Clothed in animal furs and swathed in folds of blood-red drapery, he clutches a simple reed cross for solace as he broods on the errors and miseries of mankind. The chiaroscuro is eerily extreme: there is a pale cast to the light, which is possibly intended to evoke moonbeams, but the contrasts are so strong and the shadows so deep that the boy looks as though lit by a flash of lightning. This dark but glowing painting is one of Caravaggio's most spectacular creations. It is also a reticent and introverted work—a vision of a saint who looks away, to one side, rather than meeting the beholder's eye. This second St John is moodily withdrawn, lost in his own world-despising thoughts. The picture might almost be a portrait of Caravaggio's own dark state of mind, his gloomy hostility and growing sense of isolation during this period of his life. (pg 277-278)

Despite or more likely because of its brusque singularity Caravaggio's picture 'pleased nobody', according to Baglione. The St Matthew was rejected as soon as it was delivered. Bellori gave the fullest account of events: 'Here something happened that greatly upset Caravaggio with respect to his reputation. After he had finished the central picture of St Matthew and installed it on the altar, the priests took it down, saying that the figure with its legs grossed and its feet rudely exposed to the public had neither decorum nor the appearance of a saint. That was, of course, precisely Caravaggio's point: Christ and his followers looked a lot more like beggars than cardinals. But the decision of Mathieu Cointrel's executors ... was final. Saving Caravaggio's blushes, Vincenzo Giustiniani took the painting of St Matthew for his own collection. .... Giustiniani also prevailed on the congregation of San Luigi dei Francesi to allow the painter to try again.Here's the first version of St Matthew and the Angel:

The resulting picture, his second version of St Matthew and the Angel, was accepted without demur. ... The character of the painting, and indeed the very fact that it was commissioned at all, suggests that those in charge of the commission had few doubts about the painter's ability. As far as they were concerned, it was merely his taste, and the tenor of his piety, that was suspect: if he was given the right instruction, these could easily be amended. (pg 236-237)