What do you think?

Rate this book

288 pages, Kindle Edition

First published December 1, 2010

Chapter 1, Echoes, introduces Wagner’s musical erotics by surveying important nineteenth century reactions to Wagner that have often been marginalized in contemporary scholarship.Dreyfus takes examples of opinion pro and contra Wagner that emphasize his musical and dramatic depiction of erotic sensations and actions; Baudelaire's reactions are perhaps the most famous of those cited. Dreyfus concentrates on criticism or accounts of actual performances and does not look further afield into fictional depictions beyond the over-used examples of Thomas Mann's Tristan and Wälsungenblut. I was hoping to encounter an example of Wagner considered as an aphrodisiac which I've never seen mentioned in Wagner studies: In H. G. Wells' Ann Veronica a friend of Ann's father takes her to the opera to hear Tristan und Isolde, which he seems to consider a kind of Gebrauchmusik to facilitate his seduction of her.

Chapter 2, Intentions, investigates whether Wagner knew what he was doing in composing music representing “sensuality.” It seems he knew exactly what he was doing, even if – given the mores of his time – he must be classed as a reluctant if obsessive eroticist.The core of this chapter examines how the music of Tristan closely relates to Schopenhauer's ideas about sexual desire; this is also addressed, in even greater detail, in Bryan Magee's The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy. The section on Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient might have fallen more under the heading of "inspirations" than "intentions"; a discussion of the spurious erotic memoirs of the singer was rather irrelevant but nevertheless interesting.

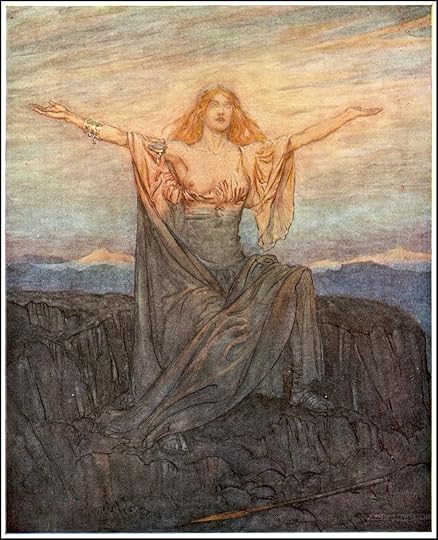

Chapter 3, Harmonies, surveys the key musical techniques Wagner developed for his erotics and focuses especially on Tannhäuser, Die Walküre, and Tristan und Isolde. With Tristan, Wagner revealed the fundamental outlines of his erotico-musical world, and though I could have gone further in discussing Die Meistersinger, Siegfried, Götterdämmerung, and Parsifal, I believe the subtle variants of erotic experience found in these later operas are better treated in specialized studies.This is a good account of how Wagner expresses eroticism in music, but it also shows the limits of Dreyfus' study. He is really interested in a kind of erotic longing rendered in tonal but highly chromatic music. Of course, Tristan is the epicenter of this expression, and his study seems most valid when discussing that work, which he treats pretty much in its entirety. Otherwise, he examines only sections of the operas: the Venusberg scenes of Tannhäuser, Act I of Die Walküre, and the Parsifal / Kundry duet in Parsifal. He isn't at all interested in examining means of erotic expression in music before Wagner - earlier he dismisses Kierkegaard's ideas about Don Giovanni's Fin ch'han dal vino saying

the musical tropes have lost their erotic appeal: Since the works of Wagner, their effect is raucous and amusing, if also tuneful and puerile, rather than sensuous and libertine.Even when older techniques of erotic expression are employed by Wagner, such as the final duet in Siegfried, Dreyfus gives them small attention. His motto might be: Nothing erotic can happen in a major key.

Chapter 4, Pathologies, considers late nineteenth-century receptions of Wagner’s “diseased” erotics to show how critics like Nietzsche unwittingly identify positive values in Wagner’s erotics at the same time that they expose the composer’s unconventional masculinity. The link between the composer’s silk and perfume fetishes and their representations in his operas seems remarkable in this light, as is the absence of his interest in “sexualizing” anti-Semitism.This chapter largely consists of the "higher gossip", or maybe not all that high. Wagner's diagnosis of Nietzsche as a dangerously chronic masturbator, Nietzsche's hinting at Wagner's inadequate masculinity, and making much too much out of Wagner's indulgence in silks, satins, and perfumes, of very particular shades and scents. Though this indulgence was definitely a matter of sensuality, Dreyfus doesn't provide enough justification for his terming it a "fetish"; the only biographical link mentioned is Wagner's childhood love of the textures and colors of his older sister's theatrical costumes. Apparently Wagner used these materials to create a womb-like enclosure in which he could work for long periods. Surprisingly, Dreyfus makes nothing of this womb imagery; nor does he take any notice of the way mention of the hero's mother enters into the Siegfried / Brünnhilde and Parsifal / Kundry duets. Perhaps Freud and his Oedipus complex are too far out of fashion in present day academia.

Finally, Chapter 5, Homoerotics, treats Wagner’s surprising regard for same sexual love (Männerliebe or Freundesliebe) as a complementary aspect to his personality. Wagner encouraged a spate of younger, sometime “homophile,” men to become passionately attached to him and this sensibility, too, surfaces in his operas.As authors like Ethan Mordden and Wayne Koestenbaum among others have documented, there is a significant section of the gay male population that take a passionate interest in opera, which in many cases goes beyond appreciation of the art and touches upon a sense of personal identity and expression of self. It therefore would not seem to make any statement about Wagner's works in particular, as opposed to operas in general, that a number of his enthusiasts were proven or likely homosexuals. Dreyfus notes a number of homosexuals and gay couples with whom Wagner was familiar and on good terms; many of these are described in My Life with as much candor as was possible at the time. Dreyfus does not mention one homosexual, Karl von Holtei director of the theater at Riga where the young Wagner was a conductor, with whom he had an adversarial relationship; this had much to do with theatrical and employment matters and nothing to do with sexual orientation, though Wagner does not refrain from ad hominem insinuations about the latter when describing their conflicts. Dreyfus' willingness to follow tangents makes this one of the few books on Wagner to mention Henry James, who enters the narrative as an acquaintance of Parsifal stage designer Paul von Joukowsky. James, who "famously loathed music" (as Dreyfus rather forcefully phrases it), declined a meeting with Wagner on the excuse of his lack of German and Wagner's (incorrectly) assumed lack of French or English.