What do you think?

Rate this book

568 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1918

For what cause and question at all will not immediately degenerate into a trial of strength for the parties? Which ones will not immediately stand in the falsifying, distorting light of politics, of party politics, that is? Politics as a source of perception through which all things are seen; the administration – skilled in the spirit of the ruling parliamentary majority of the time; the officer corps – politically demoralized; the justice department – politically poisoned; creative writing – tendentious theater and psychology on the basis of social comparison, carried to the point of tout-est-dit; and affairs, scandals, political-symbolic conflicts of the times, magnificent ones that elevate and inflame the burgher in alternating dances, a new one every year – this is the way we will have it, this is the way we will live every day. (253)

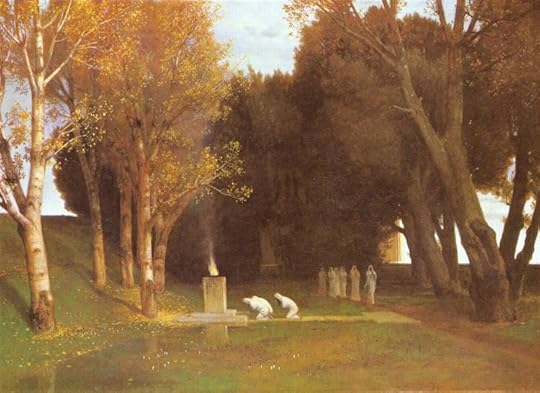

I need only look up from my table to delight my eyes with the vision of a moist glade, through whose half darkness the bright architecture of a temple glistens. From the sacrificial stone the flame blazes up whose smoke disappears in the branches. Flagstones embedded in the swampy-flowered earth lead to its smooth steps, and there sacerdotally covered figures kneel, solemnly humbling their humanity before the savior, while others, upright, in ceremonial bearing, stride from the direction of the temple to the service. Whoever would see an insult to human dignity in this picture by the Swiss artist that I have always valued and held dear, could certainly be called a philistine. (396-7)Mann wrote, or perhaps I should say compiled, this book over the course of several years in the middle of WWI and doesn't seem to have gone back over it to revise or tighten its arguments. It starts out pretty incoherently, making distinctions, such as opposing culture to civilization, that aren't readily intuitive to the reader. Some of these get clarified to some extent in the course of the book, but any hope for growing coherence is eventually dashed as Mann adds qualifications that have the form of nuance but which actually further muddy any logic his argument might achieve.