What do you think?

Rate this book

293 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1936

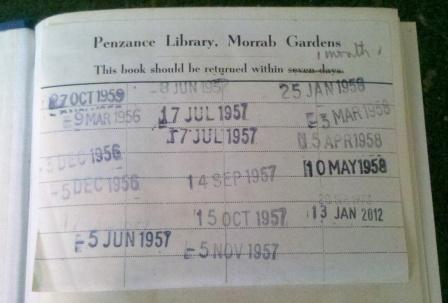

I bought the book home - I just had too after I saw that. I found that what I had was not a coventional autobiography. That, given a free hand by her publishers, the author had decided to do something a little different. She explains, with both erudition and charm, that, while a conventional biography that plots a straight line through a line can be a wonderful thing, it is sometimes more interesting to do something else. To set down three stakes, to run a rope around then to make a triangle, and then to see what is to be found inside that triangle. And that's just what she does. So this is a book that told me little about the facts of the author's life, but it does tell me a great deal about the woman she was and the things she loved. I was a little confused at first. Miss Stern jumps from subject to subject - an incident on a European holiday makes her think of Nell Gwynn, a fellow traveller brings to mind Jo March's Professor Bhaer - and for a while I felt like Alice falling down the rabbit-hole and unable to see exactly what was on the shelves. But I soon found my feet. I began to feel that I was at a wonderful literary party, listening to a wonderful raconteur a little way away. I couldn't quite reach her through the crowd, but I was still enthralled. And so I must tell you a little of what I heard. This is a very telling passage, that I so understood:

I bought the book home - I just had too after I saw that. I found that what I had was not a coventional autobiography. That, given a free hand by her publishers, the author had decided to do something a little different. She explains, with both erudition and charm, that, while a conventional biography that plots a straight line through a line can be a wonderful thing, it is sometimes more interesting to do something else. To set down three stakes, to run a rope around then to make a triangle, and then to see what is to be found inside that triangle. And that's just what she does. So this is a book that told me little about the facts of the author's life, but it does tell me a great deal about the woman she was and the things she loved. I was a little confused at first. Miss Stern jumps from subject to subject - an incident on a European holiday makes her think of Nell Gwynn, a fellow traveller brings to mind Jo March's Professor Bhaer - and for a while I felt like Alice falling down the rabbit-hole and unable to see exactly what was on the shelves. But I soon found my feet. I began to feel that I was at a wonderful literary party, listening to a wonderful raconteur a little way away. I couldn't quite reach her through the crowd, but I was still enthralled. And so I must tell you a little of what I heard. This is a very telling passage, that I so understood:“Sentimentality and that childish tendency to say, “nobody loves me and I don’t care” on the slightest provocation, made one invariably cast oneself for the lame child excluded from the good time that others were having. My yearning always to belong to a fabulous band known as “The Rectory Children” was associated with the idea that the rectory children were always having just this sort of good time, and that if you mingled with them hard, you would be yourself identified with their good time, and so escape the dire fate of being excluded from whatever was going on. These mythical rectory children, later on, were to develop into a more sophisticated group; but they would always be the group that looked to me as though they were having the best time of all ...”

“The Englishman has a curious innate reluctance to become adult. “He’s such a boy at heart, “ is a term of praise in this country. Perhaps also in other countries? I am not quite sure: “Ce n’est qu’un grand garçon” may be said indulgently in France as often as in England. Except that garçon also means bachelor, or waiter. Either puts the sense wrong ...”

Miss Stern was a wonderful observer of other women:

“The first modern girl, the first record that the difficult modern daughter was not at all a modern invention was, of course, Persephone; and Persephone could have given an interviewer a pretty good idea of her views on the old-fashioned mother; Demeter was a darling, of course; a mummy-my-sweet; but terribly unreasonable; “Mummy doesn’t realise that one’s allowance goes simply nowhere nowadays; and she fusses over me and talks poppy-cock about sitting at home after dark and it’s dangerous to talk to strangers, till I sometimes think I’ll go batty” ...”

“Now, when I meet scholastic ladies I like them, respect them, yet feel as though I were skating precariously on thin ice all the time; or rather, that my brittle ice is their solid terra firma. Will they find me out, I wonder? Find out those frightful gaps in my education?”

“Mental collections can be as dearly prized as those we keep behind glass, like snuff-boxes, fans or china cats; or the collection of a man who assembled everything that happened to be the size of a fist. I have a mental collection of moments on the stage, moments of horror, irony, beauty or tension ...”

“'A Telephone Call' by Dorothy Parker, though not in song form, is probably the most agonised, most agonising torch-song ever written. I would give you the Hundred Most Massive Highbrow Living Writers, the kind who creak and heave as they thrust their shoulders at the wheel, like figures in a frieze of Modern Labour, for what Dorothy Parker can do by not using quite half the strength in her little-finger ...”

“I am fond of dogs; deeply and unreasonably fond of them; though I have never subscribed to the platitude that the dog is “the intelligent friend of man.” For consider a spaniel, for instance; how with ears flapping, forepaws scuttering in all directions, he will chase a rabbit year after year, sometimes the same and sometimes a different rabbit but with no hope of ever catching up with it; how he will lie down heavily on a bed of your recently planted bulbs just beginning to show tender and fragile above the earth, and when you furiously holloa at him to come off, will wag his tail, will gaze up at you with love and devotion unalterable in his sherry-coloured eyes, and then roll over heavily on to his back the better to destroy the little green shoots ...”

“A eucalyptus tree once grew in our garden in Cornwall. We had signed a lease in the autumn. For seven, fourteen, or twenty-one years, of that little house and garden; and returned to take possession in the spring.

During the winter, in London, we talked of that solitary eucalyptus tree; a rare prize to find in an English garden. And while we talked it grew taller, more strange and silvery and beautiful. Not many people in England, we told ourselves, have eucalyptus trees in their front garden.

When we returned we found it lying prone across the lawn. Our Cornish landlord had cut it down to make “a gentleman’s avenue.” “Ee must have a gentleman’s avenue,” he said repeatedly. I wonder why he thought so.”

“My new watch kept beautiful time. A watch, a clock, they are the only things that can keep time. The rest of us squander it, lose it, clutch at it, are burdened with it, let it escape, cannot catch up with it, chase it, plead with it, sigh for it, die for it ...”

p 40: When we lost most of our money in the Vaal River diamond smash, the house in Holland Park was given up, and I went to live with my sister for a year or two. She had a very gay house-parlourmaid with brilliant red hair who did the splits, learnt from a dancer where she had once been in service. We never knew when she was going to do them. She would bring in the soup, put it down on the table, do the splits, laugh, and go out. Visitors liked her immensely. In the fullness of time she had a miscarriage and had to leave.

p 45: A curious list has associated itself pictorially with gaiety and a good time: meals eaten over water or beside water; on some outjutting structure like a pier, a balcony, a terrace, a boat moored up to the bank; on the terrace of a restaurant at Rapallo, over the Mediterranean; at San Francisco, sitting in a bow window thrust out on the very rim of the Pacific; in innumerable gardens, along the length of the Thames; breakfast on a balcony in Budapest looking across the yellow Danube to the Royal Palaces opposite; meals eaten beside lakes, beside streams, beside weirs and waterfalls; on a balcony in Venice; at a restaurant beside the lake of Annecy; lunch at the end of a little breakwater in Cornwall, looking back at the harbour and the fishing village.

p 125: At the present moment, renting a little villa in the South of France, I have in my service a temporary butler-chauffeur-valet-de-chambre-maitre-d'hotel who enjoys a superiority complex. Sitting by my side, in his little mauve Citroen, he admonishes me in long tirades, with the same solide conviction of uttering what was wholly new now but would presently become the Law, as Moses issuing the Commandments. First he pronounces his theme, such as: the Jealousy is the Most Profound of all the Human Emotions. Then he expands it: The badness of the Nature Humaine is, he says, because les gens are moved by jealousy and do not sufficiently control it. At the bottom, he says, the Nature Humaine is pretty bloody awful. In all such generalisations he succeeds remarkably in dissociating himself from any connection with the Nature Humaine.

p 182: You can only achieve universality by accidental means. Write the story of a few individual human beings, a few officers and men in a dug-out and their personal reactions to the circumstances of war, and because they are individual they will be true, and because they are true they become universal, and because they are universal they will become symbolical. A longer way round than by drawing them symbolical to begin with; but they prove better lasting material than those figures, vague and cloudy and cosmic, that are drawn larger than life-size to begin with; and so, having shed humanity, immediately cease to matter.

p 184: Sacrifices remind one of Stonehenge; they look very well against a sunset, but would be heavy lumber in the home.

p 198: Yet I had never seen oysters so plump, so pearly, so virginally alluring, so like those mountains seen across a lake, misty and shimmering at dawn. My partner offered my one; my partner persuaded me. Suddenly all Brighton pier, all Southend pier, all the piers of the world were sliding down my throat, with a whiff of ozone and the salty tang of those crusty, barnacled, seaweedy bits of structures right at the end, half under water, below the boarding and the bandstand. The sea, grey and green, Swinburne and sharp keen kisses, spume of the waves blown back, and my picture on the wall, all slid down my throat.

p 218: When I reached home, I found myself alone in the sitting-room; the broad high window that looked straight down the Eastern vista of Savile Row, turning dark Mediterranean blue as the daylight ebbed and a richer colour filled up the luminous rectangle between the straight line of burgundy taffeta curtains that fell heavily on either side of it. I could lie back in my armchair, in that faintly enchanted silence, that droning peace, lulled and oblivious as though I were under the sea "full fathom five: and had leaned how to breathe down there. The slightest sound would have shattered tranquility, except from the traffic far below, and that drifted up to me steady and rhythmic as a waterfall; not, as it so often was, spasmodic, shrill and jerky. I had not been able to buy a picture; nevertheless contentment lay in my lap like a purring drowsy cat, so nearly tangible that I put out my hand to stroke it.