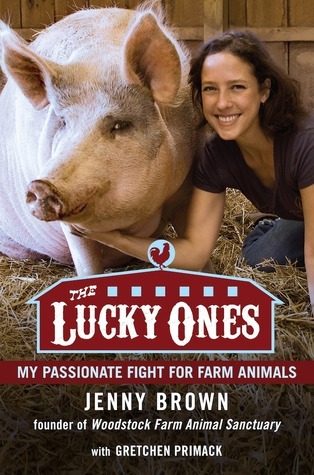

Although not as technically proficient in writing style as other recently-published animal advocates Gene Baur and Wayne Pacelle, The Lucky Ones by Jenny Brown may reach a wider audience with its conversational style and mix of memoir, humor, and education.

Diagnosed with childhood bone cancer, Brown suffered a leg amputation at age ten. This early trauma and the resilience required to cope with it meant that Brown grew to be highly empathetic with other helpless beings. When Brown adopts a weak, runty kitten, she begins upon a journey that would end with her heading one of America’s best known farm animal sanctuaries.

Like most of us, Brown’s first connection with the animal world was through a pet. It seems that this is the audience she is primarily talking to with this book—those legions of self-proclaimed animal lovers who see no irony in stroking their dog’s head with one hand while holding a BLT in the other. Brown presents us with information that the animals we eat aren’t so much different from the animals we love:

Animals are here with us, not for us—that’s my motto. … Andy the steer, who also escaped his fate as veal chops, trots over when he’s called, just like a dog. And Ophelia the hen, whose wings and thighs would have ended up on a plate, just wants to crawl into your lap to snuggle and mooch your warmth—just like a cat.

So, essentially, she’s not trying to convince us that animals are important; she’s making the case for those who already think that some animals are important to extend their circle of concern a bit wider. And unlike our fang-toothed carnivorous pets, we are not required to eat other animals to survive. It’s mainly comfort, inertia, and tradition which drive what Brown calls “the systemic, rampant, unnecessary cruelty to these very beings for the sake of Buffalo wings, cold cuts, and hot dogs.” And those really aren’t good reasons at all. Notes the author:

Author Michael Pollan put it well: “There’s a schizoid quality to our relationship with animals, in which sentiment and brutality exist side by side. Half the dogs in America will receive Christmas presents this year, yet few of us pause to consider the miserable life of the pig—an animal easily as intelligent as a dog—that becomes the Christmas ham.”

Although Pollan is a loud n’ proud omnivore, his observation about the nature of our relationship with animals is spot on. Brown elaborates:

Pigs are more intelligent than dogs—and, in fact, most three-year-old children. I’m sure even the many people have studied pig intelligence have been surprised by their findings … [I]t’s trendy these days for hipsters to wear clothes that say things like “I Love Bacon” or “Bacon Makes Everything Better!” It makes me sad how far removed people are from the reality that bacon came from a sentient animal who lived a life of deprivation, pain, frustration, and fear, all for a food that we have no nutritional need for.

I couldn’t agree more. Every time I hear or see odes to our current national obsession with bacon, I think things along the lines of—Ripping the testicles out of a conscious, screaming piglet? Imprisoning a mother sow in a cage so small she can’t turn around? How is that cool, funny, or appealing?

If similar mutilations and practices were imposed on cats and dogs, there would be public outrage. But the majority of people don’t realize it’s happening to the animals that land on their plates, or stop to think what animals go through before they’re eaten. A turkey, like any other creature with a nervous system, experiences pain, which is, after all, a survival mechanism.

And that’s the truth. While farm animals continue to suffer ever more shocking deprivations in unfathomable numbers, our love of pets has reached such absurd levels that it’s not unusual to find social media campaigns on behalf of individual dogs who have actually killed innocent people.

True, our information-saturated age has many of us more aware of farm animal issues, even if most of us aren’t yet willing to lesson our impact. We have a natural affinity for and desire to protect babies, so it is very common for omnivores to proclaim that they won’t eat veal or lamb. Yet, nearly all of such people have no problem eating chickens, who are often even younger than veal calves and lambs when they face the knife:

[Broiler chickens] are so immature when killed, the females haven’t even begun to lay eggs. … Unbelievably, “broilers” grow so quickly that they are slaughtered when they’re still babies, just over a month old. … Their birth to death is forty-five days. That’s how far we’ve gone, how severely we’ve manipulated their genes.

While their bodies are morbidly obese, their heads are still covered with down and they’re still peeping when they’re loaded onto those slaughter-bound trucks. To eat commercially-produced chicken is to eat baby birds. The shrink-wrapped chickens fancifully named “Cornish game hens” are even younger still.

Even so-called “happy meat” animals face quite unhappy manipulations, Brown asserts:

It’s trendy for consumers to buy conservation breeds, but as natural as people might want the turkeys to be for health or conscience, the producers want the same extra pounds when it comes time to sell them by weight. Consumers don’t realize that these birds are still genetically manipulated for profit. There’s nothing really natural about it.

Before staring her sanctuary, Brown also worked as an undercover investigator. She introduces us to the sounds, smells, and sights of major Texas stockyards as she sneaks in a hidden camera to document the atrocities. She notes a prominent sign at a stockyard that warns, NO PHOTOS OR VIDEO ALLOWED. Gee, I wonder why.

As the flurry of “ag-gag” legislative proposals indicate, Big Livestock would much rather prevent consumers from seeing how farm animals are treated than clean up their act. In addition to the cruelty that arises simply from raising thousands of animals in crowded conditions, a hallmark of undercover videos of stockyards, factory farms, and slaughterhouses is the pointless abuse of animals by some workers. Brown has some insight into this behavior:

This fits the sometime pattern of the abused becoming the abuser. Some workers…tired of being the low man on one or more totem poles in their own lives, lash out at beings even “lower” than they are. Other workers take out their frustration at the misery of their work on creatures who can’t complain, retaliate, or get them in trouble … Other abusers are simply those with a penchant for violence who may be kept in check by other sectors of society but who have free reign in the hell of a slaughterhouse or farm.

Explaining why she chose to start a sanctuary for farmed animals, Brown writes,

Compared with the number of farm animals living and dying each day, dogs and cats are hardly a blip on the screen. Ditto lab, fur, and circus animals. Of course, I would never stop advocating on behalf of those populations, either, but I could hardly get my head around the fact that farm animals make up a staggering ninety-eight percent of domestic animals in this country.

Brown envisioned a place where people could meet rescued farm animals and learn about them as well as their commercial abuse and exploitation. And as people poured in, that’s just what began to happen.

At the end of the tour, the man turned to his children and said, “Guys, I’m ashamed.” He explained that he’d always assumed that turkeys were dumb and didn’t possess individuality or personality. He had thought of them only as cold cuts and the Thanksgiving meal centerpiece. But it was obvious after spending the afternoon with the birds, he said…”They’re smart and friendly---I never imagined.”

Imagine the serendipity of a goat with a severely injured leg finding his way to Woodstock Farm Animal Sanctuary. When Albie the goat must have his leg amputated, Brown contacts her prosthetics maker to see if he can use some of the same technology that helped her to help Albie. The idea of a woman with a prosthetic leg caring for a goat with a prosthetic leg was just too much for the press to resist. The New York Times descended upon the little farm to run a feature.

Before reading about Albie, most people had never seen animals like him as anything but “livestock.” Now they were revisiting their assumptions. They’d heard of paralyzed dogs being custom fitted with carts to help them get around, but that followed the usual course of dog-as-family-member thinking that much of our society subscribes to. But this story was something different. Are goats worth that much trouble? … Albie’s story turned him into an individual: he had a name, he was loved, he wouldn’t be used for anything, and he had been through an awful ordeal.

Albie’s one-of-akind false leg was breaking new ground. Unlike companion animal medicine, Brown explains, farm animal medicine “is traditionally about keeping an animal’s heart beating just long enough for “it” to walk to an untimely slaughter.”

Ultimately, the Woodstock sanctuary and the book are best embodied by the Albert Schweitzer quote “Think occasionally of the suffering of which you spare yourself the sight.” Of factory farming cruelty, Brown laments:

I’ve always been puzzled that people otherwise willing to question norms and think for themselves—people who seem really caring or compassionate, who profess their love for animals—have a blind spot when it comes to their role in keeping animal industries wealthy and widespread. There are so many artists, educators, activists, freethinkers, and just plain good people who will question many mandates and customs and work to understand issues—and shut their ears to this particular one.

I’ll conclude with these powerful words from the author:

Whether we like it or not, today’s consumers are responsible for the worst systematic animal abuse in world history. We can point fingers at the Big Bad Corporations—and I do—but this system is sustained by consumer demand. If we don’t enable corporations to profit from suffering, they can’t. It’s incredibly empowering to take a stance that moves us all in that direction.