Every page of this comprehensive overview of Cinema exhibits Thompson’s encyclopaedic knowledge and erudition in the field. He begins more or less from the “beginning”, with Eadweard Muybridge’s photographic studies of animal and human motion, right through to the first decade of the 21st-c. In this sense, the book can be seen as an historical chronology, and this is satisfying in its own terms. However, as Thomson himself declares, this is more a series of personal meditations on a century of cinema-going and, from this perspective, it permits Thomson to range relatively freely to and fro, making connections and links across the time-frame — and the trip is always informative and entertaining.

The text is in four parts: The Shining Light and the Huddled Masses; Sunset and Change; Film Studies; and Dread and Desire. Of these, the first part (covering the first half of the 20th-c) is given the largest share. It is this section (in my opinion) that the title of this book (The Big Screen) derives. This is not to say that we no longer have Big Screens (obviously) but it does convey the way the Movies were “understood” then. By the mid-20th-c, with the advent of television (which became the “Small Screen” (and today that early television small screen has already passed into history as larger and larger television screens have blossomed with the new technologies)) the earlier understanding was more firmly established in the public mind as being the era of the Big Screen… and with it came the idea of the Big Studios and the Big Stars… and a flourishing of “scandals” to whet the appetite (still with us today).

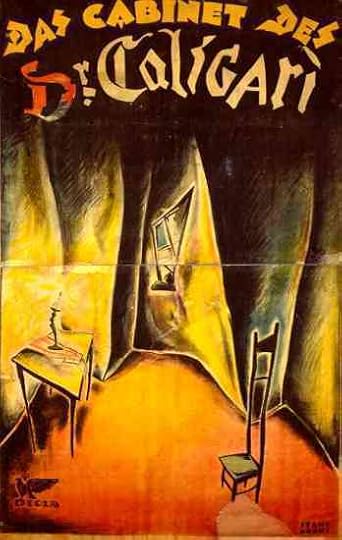

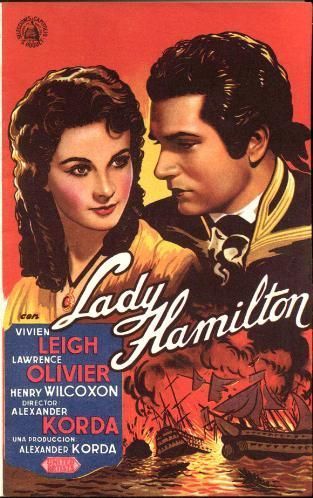

One must not forget that this time in history covered the international Great Depression, sandwiched between two World Wars. More than anything else the devastation this caused in Europe allowed the United States to benefit, as artists, writers, directors, actors fled there (particularly to Hollywood) to establish Hollywood as the predominant global powerhouse for the Movies.

All this started to change mid-century with the emergence of a series of New Wave criticism and re-evaluation attacking what was then perceived as a stultifying effect of “traditional” cinema. New ways of seeing, recording, presenting films from other countries created a revolution in awareness and appreciation. Film Societies, Film Festivals, and Film Study courses sprouted everywhere; nothing would ever be the same again. Creativity was stimulated, aided and abetted by new technologies with lighter cameras, sound recorders and improved film stock sensitivity, allowing for a vast flourishing of film product which continues to this day.

Cinema has always been influenced by technology, and its influence has not yet ceased its relentless march. In the early days film had to find its place in competition with stage and theatre productions, develop methods of narrative peculiar to cinema, particularly with editing techniques, and deal with the problems of adding synchronised sound, and colour improvement. When a certain artistic level had been achieved, it then had to tackle the threat of emerging television technologies, then with video, laser technologies, computer generated graphics, mobile telephones with digital short movie capabilities, on-line streaming on your computer, ipad or mobile phone, etc.

Film Schools and the development of academic courses in film, communications, Information Technologies, digital manipulation, and so on, combined to create and develop new phrases and descriptive words for more in-depth analyses. One now had to learn how to “read” a film, not just watch it. Once the academics get their hands on something it does not take long before new jargon is sprouting everywhere — and not necessarily always to the edification or understanding of all. Philosophical discussions on truth, reality, authorial stances, etc. also caused more heat than light in many cases.

Awareness of just exactly how some films are made raised questions as to whether there was anyone ultimately in charge of what finally appeared on the screen, and that included the director (let alone increasing influence by actors and actresses as to whether a film enhances their reputation or not). Nowadays as a rule neither the scriptwriter nor the director appear to have absolute control — and there is some justification in the consideration as to whether they ever did — and marketing techniques have taken over much of the final say in “big” movies, ensuring that just about everybody involved in the production is covered one way or another. This actually results in “independents” being more in a position of having some greater control than the big boys — and that includes pay television giants which have managed to attract scriptwriters and directors in their droves; but which tend to result in (require?) committees of writers and their co-workers to maintain a certain “quality” to hours, months and even years for their often mammoth productions.

The combination of all these things has resulted in an exponential growth in just about every type of film genre that can be created, and that includes cross-over mixed genres. Nowadays just about anything goes, and just about anything is also available more than ever to just about everyone. Digital technology has changed the very nature of Cinema: one can hardly call their DVD a “film”, nor does the technology of the many new screens we have replicate the 24 frames per second developed for film as film (there is no blank screen between frames: some part of the video screen is always “lit up” — I have often wondered whether this physical effect actually affects the way we perceive the images on the screen (does the blank (black) screen between each frame of a film stimulate us psychologically to be more alert? does the non-blank television/monitor/computer/phone screen contribute to us becoming more soporific in our viewing habits? (maybe this might explain the increasingly erratic fast editing we seem to find occurring more and more in films today to compensate for this?)).

Our technology permits us to access our films/movies/cinema in any way we wish, to interrupt the flow whenever we wish, in any order we wish, to view them alone, on public transport, in daylight, or wherever. One can fast forward at different speeds, or even slow down to even interminably long “presentations”. Everyone can literally play around with the product in any way one pleases, regardless of the original intent (if there was one) of the product itself. On one level this represents a largesse and freedom which can be considered exciting and unpredictable, but it can also result in excesses which in the long run could prove counterproductive.

At the moment, however, that caution does not appear to be something anyone is heeding. Thomson acknowledges this in his postscript, in which he indirectly reiterates the concept of the Big Screen more applicable in the early art of the 20th-c, by positing the vast numbers of different “Small Screens” to be found everywhere today. He titled this postscript with a delightful pun “I Wake Up Screening”. Fun, in a sense, but also there is a sense of dread… Some readers might find it ironically amusing that, in my Penguin edition of this book, there is a typo in the Table of Contents which gives the title of the postscript as “I Wake Up Screaming”!

One thing was clear for me: the first part of this book came over as a kind of eulogy for the Cinema of the early half of the 20th-c. That kind of experience was unique and universal. That special shared communal feeling presented in darkened halls and theatres during the time of two World Wars and a Depression has well and truly gone. If we are lucky, we might occasionally be able to catch a glimpse of what it must have been like for the audience to feel the comfort provided by the Big Screen, by making them laugh and cry, by providing some little assurance and respite from the difficulties just about every single person in those audiences would be experiencing, and giving them the strength to carry on by making them dare to dream of better and happier times.

Of course, there were other wonders the Big Screen could provide: spectacles of history and faraway places, information about many things, provocative concepts to stimulate the mind, and so on. In a way the Cinema still provides those qualities we so love and enjoy, by entertaining us, but also by dealing more with personal problems and difficulties as they relate to our own times, as well as with the difficulties and problems of many others from different cultures and places. The potential for this remains a central aspect of Cinema today, and will probably always be so.

As mentioned above, despite following the story more or less chronologically, Thomson is not claiming historical absoluteness: he is more concerned with providing us with his own personal meditations on a century of Cinema. One does not have to agree with everything he writes (in fact I occasionally found myself in disagreement with some of his statements) but that makes this book all the more interesting. Regardless of one’s own personal predilections Thomson’s knowledge and erudition shine through this book, making it a pleasure to read.