“I see the boys of summer in their ruin

Lay the gold tithings barren,

Setting no store by harvest, freeze the soils.”

-Dylan Thomas

We are approaching Memorial Day. The weather should be heating up soon, and for me nothing epitomizes summer like a baseball game played on a hazy afternoon. Drink in hand on the porch with a radio by one’s side, baseball is the soundtrack of summer. This year there may be no baseball, and, if there is, it will be in abbreviated form only. In order to simulate the baseball season, I have been reading heavy doses of baseball books- history, biographies, travelogues. While nothing can substitute the actual games, at least these books allow me to immerse myself in our national pastime. Before sports ground to a halt, the baseball book club had chosen to read the seminal works of gifted sports writer Roger Kahn, who passed away this winter. Kahn lived during an era when the line blurred between sportswriters and ballplayers, with the two groups enjoying a close camaraderie. Reading Kahn’s classic The Boys of Summer takes one back to a bygone era when baseball was truly America’s game and its players were revered by countless Americans.

Roger Kahn was born on October 31, 1927 to Gordon and Olga Kahn nee Rockow of Brooklyn. Olga’s father Abraham, a dentist, lived with the family, and the Kahns navigated through the depression largely unaffected. Olga Kahn was a professor of classical literature and did not understand why her son, an all American boy, wanted to play and watch baseball. Gordon, also an intellectual, secretly spent hours playing ball with Roger, hoping to mold him into one of the top youth players in the area. When Roger was ten, Dolph Camilli lead the Dodgers to their first pennant, and Gordon managed to take his son to a few games at nearby Ebbets Field. Roger became a fan against his mother’s wishes and continued to follow the Dodgers on the radio listening to the southern lilt of Red Barber, or, if he was lucky, by attending a few games each home stand. By the time Roger entered his teen years, it was apparent that he was not going to be a future third baseman for the Dodgers, but he showed aptitude in his writing, and his father attempted to outline his future for him as a magazine writer or journalist.

Through connections from his father, Kahn joined the staff of the New York Daily Tribune in 1948. He was on the sports staff when the Dodgers lost to their rival Giants in a playoff in 1951. By that point, Dodgers beat writer Harold Rosenthal had gotten burnt out covering the Dodgers on a yearly basis. A week before 1952 spring training was to start, the job was offered to Kahn. He was all of twenty four years old, younger than most of the players on the team. As a lifelong Dodgers fan, this was the chance of a lifetime, and Kahn fortuitously became the Daily Tribune’s Dodgers beat writer for the 1952 and 1953 seasons. Taken under the wing of Rosenthal and Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen, Kahn quickly learned the ins and outs of baseball beat writing. It was a tough profession as he had to balance his position as a fan with that of a writer, and he had to remain in the good graces of the both the players and management during a time period where sports writers traveled on the team trains and planes. Kahn had to earn his place in the sports writing hierarchy because this was the era of Dick Young, a brash reporter for the rival New York Daily News. Young lasted longer than Kahn as a reporter by writing exposing stories, ones that would sell newspapers. Kahn, on the other hand, gained credibility and copy from the players by not writing controversial stories unless it was big news. A number of players on the team counted Kahn as a friend. By developing lasting relationships with core members of the Dodgers, Kahn was able to reconnect with them when he decided to write this book eighteen years later.

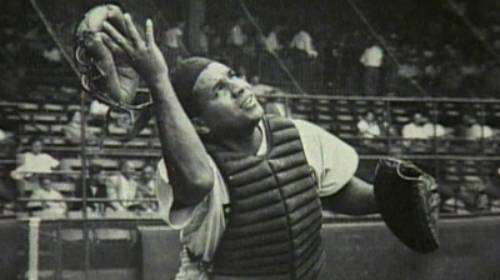

Kahn was not fortunate to be covering the Dodgers when the team of aging stars lead by PeeWee Reese and Jackie Robinson finally won the World Series in 1955. After the 1952 and 1953 teams lost heart breaking Series to the Yankees, Kahn left the beat, realizing that there was more money to be made as a free lance reporter for magazines. He wrote stories for Sports Illustrated during its infancy and found himself covering the 1959 World Series for the magazine won by none other than the Los Angeles Dodgers. That team was comprised of a new generation of players. Robinson had retired before the team left Brooklyn, and catcher Roy Campanella had been paralyzed in an automobile accident two years earlier. Reese was aging, and Brooklyn pitchers Carl Erskine and Joe Black had been replaced by emerging stars named Koufax and Drysdale. Only California native Duke Snider was determined to play regularly in Los Angeles, but he, too, was replaced as an everyday player in 1960. The era of the Brooklyn Dodgers team had come to a close, but ten years later Kahn wanted to see what happened to his boys of summer. How did they enjoy retirement or a second career during an era when players were not paid what they are today? Between 1968 and 1970, Kahn tracked down most of the members of the 1953 Dodgers to see how the rest of their lives were treating them.

Kahn found out that most of the Dodgers were happy to live a quiet life in or near their hometowns after their ball playing days were done. Most of these men had been gifted as teens and were fortunate to play professional baseball, but some were shy and chose to spend their lives outside of the limelight. PeeWee Reese, a hall of fame shortstop, ran a bowling alley in southern Indiana near his hometown of Louisville, and Preacher Roe returned to Ozark country in Arkansas. Even the all American boy Duke Snider tried to farm avocados in Fallbrook, California. While his farm failed, primarily for monetary reasons, even Snider was content to enjoy a relaxed, California lifestyle. In a moving section, Kahn visited Carl Erskine in Indiana, where he moved back so his youngest child Jimmy, developmentally disabled, could enjoy a quiet life. Gil Hodges remained in the spotlight as manager of the expansion New York Mets, and Jackie Robinson remained active in business and politics for the rest of his life. Kahn referred to him as the Lion at Dusk, and his visits with Robinson and his family toward the end of his life were especially poignant. For the most part, the boys of summer returned home. In some cases, few people knew that they even played on pennant winning baseball teams. Kahn revealed how his friendship with these players remained as the game moved toward modern times and how, as they neared middle age, most retired ball players are not so different than the average American. Names and exploits on the field become oral history and part of American folk lore as the players themselves fade into the past.

With no Boys of Summer to cheer this year, it is always a treat to read about a bygone era of the game’s past. Brooklyn of the 1950s was a simpler era when players stayed with the same team for their entire career, and fans associated with the players and the ebbs and flows of a long season. Roger Kahn launched his illustrious career as a beat reporter covering the Dodgers, yet, in essence, Kahn was a fan, the same as the average American. He just happened to be fortunate to gain rapport with classic ballplayers Robinson, Reese, Snider, and Hodges at a time when the Dodgers were becoming part of the American psyche. Over the course of his career, Roger Kahn wrote a number of seminal baseball books, where he closely followed one team for a number of seasons. The Boys of Summer came out to some acclaim from baseball fans, and was viewed as too long and intellectual by critics, yet over time has cemented its place as one of the classic baseball history books. There are few reporters left like Roger Kahn. He and the other members of his bygone era are sorely missed by baseball fans and players alike.

4.5 stars