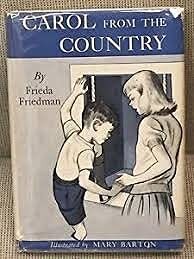

Subversively published by Scholastic Book Services in 1966, some 16 years after its original publication date, ‘Carol’ (Original title: ‘Carol From The Country’), by Frieda Freidman, is a searing, scathing, shocking novel melding equal parts of existential philosophy, Machiavellian theory of self-defined ethics of behavior, Freudian sexual intrigue and mid-century American social dread.

The plot is deceptively simple: the anti-heroine, the titular "Carol", has been abruptly relocated from her beloved, idyllic country house to a filthy, crowded, noisy, and (worst of all, for Carol) tastelessly accoutered tenement in New York City due to her father’s shoe store’s bankruptcy. Hence, the reader is immediately thrust into a bifurcated representation of the social theory of gemeinschaft vs. gesellschaft (which becomes, throughout the novel, a sort of ghostly non-physical character) paralleling the failure of Carol’s father (in a Freudian twist, never assigned a name and only referred to as “Daddy”, even by his wife) to maintain his social and economic independence with the failure of post-war America to retain it’s pastoral tradition. “Daddy”, once the proud owner of his own business as well as an idyllic country farmhouse, is reduced to moving his family into Manhattan and becoming a mere employee, literally kneeling at the feet of the customers who are no longer his own and include, to Carol’s horror, “foreign people”. In the kneeling of the father before unknown and unidentified male customers, author Friedman also slyly hints at the underground homosexual culture of the 1950s, a world subterranean world wherein and entire subset of the population made tentative steps (the very word “steps” another of the author’s unstated puns, “Daddy” working in a shoe store) toward ultimate liberation, if not entire societal acceptance.

Carol has a brother and a sister, a younger pair of twins named Johnny and Jinny (short for Virginia, representative of the mid-century American female reduction by the outside world to a mere diminished version of one’s self, and of course, a virgin) who appear as allegorical figures representing the youthful enthusiasm of a post-WWII world. It is Johnny and Virginia (I choose to identify this young woman by her full name instead of the disrespectful diminutive foisted upon her by an intellectually undeveloped public) who face the first subliminal sexual threat in the novel as their downstairs neighbor, the spinster Miss Tyler, bangs a broomstick on her ceiling directly under the piano seat on which the twins sit, also banging, but on the piano keys. This is another set-piece triumph of Freidman’s, illustrating the entire range of pre-war sexual repression with post-war sexual revolution in the vision of the virgin spinster yielding a phallic object at the new generation, her “banging” on the ceiling representative of another variety of banging obviously missing from her life.

Miss Tyler is worthy of serious dissertation of her own, but for the sake of brevity let’s make passing mention of the most important aspects of this barely drawn yet fully developed character. We know she is elderly; we know she has no friends or family; we know she lives alone in an apartment darkened with permanently closed blinds. Miss Tyler claims to get migraines due to light and noise sensitivity, but what is she really hiding from, or, more directly, what is she herself hiding? Of course author Friedman employs the character of Miss Tyler as a foreshadow warning to Carol of what Carol’s life could turn out to be, but a closer reading of the novel, focusing textually on the character of Miss Tyler, will be necessary to fully understand the author’s inclusion of her.

The most prominent “outsider” figure in the novel is Pat Daly (a boy, and yet another psycho-sexual complication of the author’s in naming this character with a moniker both male and female). His flaming red hair and invasive personality are representative of the threat of Communism in post-war America, and his frequently mentioned freckles a representation of the new populations Carol is exposed to in the city, each “spot” on Pat’s face a constant reminder of a new “sort” of person Carol must encounter. (Spoiler alert: Carol does, ultimately, reach a tentative if limited acceptance of her new neighbors, saying at one point of one “You can’t help admiring him, even if he is a foreigner”).

Sex looms large in the presence of Carol’s new friend Betsy, a pretty, popular, and well-dressed girl relocated to the city from, wink-wink, “down South”, who refers to her girlfriends as “Honey”. Carol’s fascination with Betsy, her physical perfection, poise, and popularity with boys offers a riveting illustration of nascent female sexuality. Though Carol never quite achieves the closeness with Betsy that she desires, Betsy does allow a bit of hand-holding and chaste good-bye kisses.

The clash of new tastes in art in the late 1950s is also featured in a white-knuckle episode featuring a painting contest presented by the library. Carol enters one of her praised, representational pastoral images and smugly imagines she will win the contest and not only achieve the popularity she feels she so deserves but also quash finally the more modern, abstracted cityscapes painted by the janitor’s daughter, Christine. One could complain about author Friedman introducing too many “other” elements in the character of Christine (descendent of a widowed janitor, an only child who lives in the basement) but the character succeeds. I’ll not reveal the outcome of this part of the novel; it is a shocker.

And, finally, what do we make of this “Carol”? The child who is told by her own mother “You do have talents; you just have no talent for friends”? Such is the complexity created by the author that at points throughout the novel we, as readers, think “Poor Carol, so many challenges so bravely met”, and mere paragraphs later revise our opinions to “Wow! That Carol is a real C-U-next-Tuesday!”

Though not for the frivolous reader, ‘Carol’ (Original title: ‘Carol From The Country’) is highly recommended to those interested in mid-century American mores, brilliantly developed, oblique plotting, and classic Existentialist philosophy. Miss/Mrs Friedman has, indeed, written a classic for the ages.