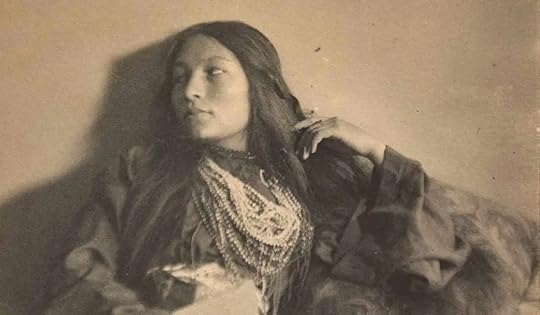

Zitkála-Šá wrote during the turn of the 20th century, largely as an activist for Native rights in Congress. I found her to be a very interesting woman that I couldn't quite pin down.

The collection opens with her interpretation on Native legends, which I found to be an apt segue to her original short stories, following, in many ways, similar structures to the legends, but where Iktomi the 'wily spider' and Iya the 'camp eater' are replaced by the 'pale faces,' come to deceive her people of their land and rights.

Perhaps the centerpoint of this collection are her semi-autobiographical stories about her time in Native boarding schools. In my own education, I have been taught that these efforts at forced assimilation were one of many terrible actions taken by the US government against Native Americans—families were enticed by the promise of education and a better life (from the very people who stripped them of their land and rights) only for the children to be severed from their families, forced to forget their native language and culture, and often treated violently. What I don't quite understand about Šá was her dedication (if that's the right word) to the education system. When she first arrived at the school, she describes her shock at the sudden severance from her culture, including the cutting of her long hair. Upon graduation, however, she worked as a teacher at the Carlisle school, one of the most notoriously aggressive forced assimilation schools for Native children. She was even sent to recruit new children to attend the school, until she seemed to realize the harm she was doing. I'm confused by the dissonance between her descriptions of early life and her choice upon graduation, and she never expounds on it. At the same time, it doesn't escape me that she felt lured to the school by, like Eve, the promise of red apples, something she had never eaten in her childhood. Perhaps she blamed herself, in a way, for giving in to the temptation, only to realize her sin later in life.

The latter half of the collection contains her activist essays from later in life, largely focused on obtaining citizenship for Native Americans (who, shockingly [or perhaps to no shock at all considering the history of the US government], weren't granted US Citizenship until the 1920's). Her patriotism stood out to me in these essays, as she describes her admiration of American democracy—maybe it's a product of her audience as she appeals to the US government (in their claims of brotherhood, how can they ignore the first American citizen?), but at times it felt genuine. Nevertheless, this patriotism, or act of such, dissipates in later essays, as she becomes increasingly frustrated and directly attacks the racism and injustice of the US government. I particularly liked the three "California Indian" chapters:

"A few weeks ago a party of tourists stood under some big trees and exclaimed about their height, their circumference and their reputed age. I ventured the remark: 'If only we could understand the language of these big trees we might learn interesting things of the past, the experiences of ancient people now gone away to the unknown.' A kind-faced gentleman with iron-grey hair pleased me greatly with his quick reply: 'We are learning. They say, 'Take off your hats.' We obey.' It was then I longed to tell some of the things the big trees in their seeming silence were fairly shouting to me, an Indian woman, but words are stubborn things. They failed to come. [...] Catastrophe it was when both the big trees and the ancient race of red men fell under the ax of a nineteenth-century invasion. Could their every wound find tongue I am sure not only pebbles but mountains of stone would rise up in protest."