Each time a new novel set in the European theatre of WWII emerges, the chorus of “Do we need another WWII novel? Haven’t all the stories already been told?” follows. And then we go on to devour the likes of The Narrow Road to the Deep North and All The Light We Cannot See. Good story is good story. If the setting or theme seems tired to you, move along, please.

So, too, could we lament the novel of the dysfunctional Irish family. From James Joyce to Edna O’Brien, Colm Tóibín to John Banville, we’ve read destitute, down-and-out, drunk. And then there’s Mammy. But we never tire of great story. And I personally never tire of Ireland.

And then there’s Anne Enright, who specializes in the particular misery of the contemporary Irish family. But you noticed that I gave this five stars, didn’t you? That’s because it’s damn near impossible to be tired of reading transcendent writing.

Her latest novel, The Green Road contains echoes of her 2007 Man Booker Award winner, The Gathering: it features a disjointed Irish family dispersed into a diaspora prior to the Celtic Tiger boom, reunites at a moment of familial crisis. In The Gathering, it is to mourn the suicide of a brother. The narrative is told through the perspective of a sister, one of twelve siblings, living in the rarefied suburbia of 21st century Dublin.

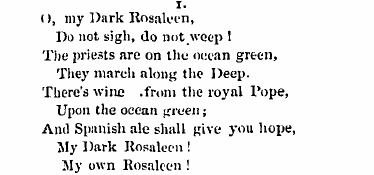

Yet even with similar themes, The Green Road is something else entirely. Set not only in Enright’s verdant, damp Co. Clare, on Ireland’s west coast, but in Dublin, New York, Toronto, and Mali, it shifts between the perspectives of the four Madigan children: Dan, Emmet, Constance, and Hanna, as they lean away from the west of Ireland and the emotional machinations of their mother, Rosaleen.

From the opening salvo, when Dan declares he is joining the priesthood and Rosaleen commences to weep on the Sunday dinner apple tart, the story sends us scattering across decades and borders. In 1991, eleven years after Dan breaks his mother’s heart, he is no longer an acolyte of the Catholic church. Engaged to his Irish childhood sweetheart, he descends to New York while she completes her studies in Boston. There he begins to admit to and explore his homosexuality, at a time when AIDS is decimating the city’s gay men. Enright immerses us in this world, but she circles around Dan, showing us instead the men he becomes involved with. Dan is more shadow than character. It is brilliantly done, for Dan is not yet fully realized as a man, not while he is still in denial, living half-truths.

Constance then enters the scene. It is 1997 and Constance waits in a hospital lobby in Co. Limerick to learn if the lump in her breast is cancer. She is the only Madigan child not to have strayed far from home. Her life is solidly middle class; in a few years, she will become part of the new wealth only just beginning to take hold in the Republic. With three children, a Lexus, an expanding waistline, Constance is the dependable one, the one who looks after Rosaleen. She too went to New York City once, but it was “the place you went to get a whole new life, and all she got was a couple of Eileen Fisher cardigans in lilac and grey.”

Perhaps deserving of a novel all his own is Emmet, the son and brother who becomes an ironically self-absorbed aid worker in West Africa. We meet Emmet in Mali, circa 2002, in a story about wasted love and a stray dog. Enright’s descriptions and characterizations capture all that is surreal about white, privileged expats trying to make a difference in a world that has little use for their clumsy, unreliable services.

Hanna, always the little sister, is rapidly aging out of usefulness as a Dublin-based actress. She has “the wrong face for a grown-up woman, even if there were parts for grown-up women. The detective inspector. The mistress. No, Hanna had a girlfriend face, pretty, winsome and sad. And she was thirty-seven. She had run out of time.” Hanna is barely holding on as the mother of a toddler. She’s drinking, Hanna is, but look, it’s 2005 and Ireland is abloom with wealth and possibility: surely it has room for her . . .

Curiously, the novel ends before the recession cuts Ireland off at the knees. But not before Rosaleen decides she will sell the family home, a threat that brings all four Madigan children back to Co. Clare and “The Green Road” of their childhood for Christmas.

This is a mannered novel, perhaps the most conventional that Enright has written, but it is so rich and full. Each chapter, each change in character perspective, could be a brilliant stand-alone short story. Enright polishes to a sharp gleam the details of setting and character, the ripe dialogue, the emotional ebbs and flows; her skill is breathtaking. There are times when her prose is lyrical and poetic: “The slope of raw clay had been ablaze, when her father passed along that way, with red poppies and with those yellow flowers that love broken ground.”; others when it is raw with reality: Dan was a year younger than Constance, fifteen months. His growing up struck her as daft, in a way. So she was not bothered by her brother’s gayness—except, perhaps, in a social sense—because she had not believed in his straightness, either. In the place where Constance loved Dan, he was eight years old.

The Green Road is a slow burn of familial love and disappointments, a purely Irish story that resonates beyond place and time, somehow both starkly rendered and lushly realized. Gorgeous, heart-tearing, highly-recommended.