After sifting through a staggering quantity of contradictory interviews, testimony, historical opinion, and even bald speculation, Philbrick succeeds in creating a new narrative of the ill-fated Custer and the Battle of the Little Bighorn. It is a narrative that bypasses ideology and blame, to refocus on the unbroken connection between historical events and their consequences. It is also a narrative that captures the very human actions that are lost in the approach of a formal inquiry which assumes a fictive and mechanical rationality not unlike the decision-making model posited by an earlier generation of economists.

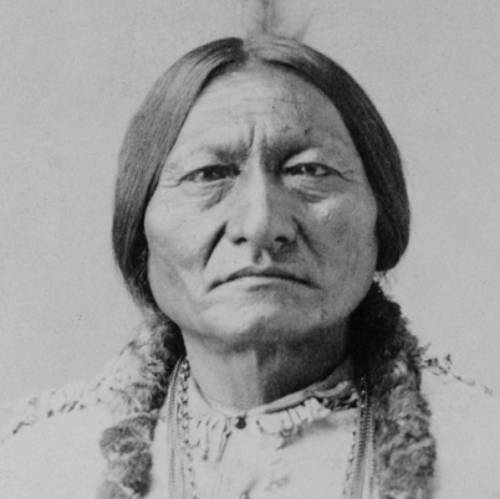

The tribes of the Great Plains were part of a larger, century-long westward displacement due to white settlement. Inter-tribal warfare was a cultural focal point, with emphasis on individual bravery, swift raids conducted on horseback, and traditional enmities, as between the Sioux and the Crow. The apparent coalition evidenced in June of 1876 was a product of ecology more than politics. The southern herds had been decimated by the building of the railroad and the predations of buffalo hunters. Tribes had been forced from the Black Hills when gold was discovered. Failure to supply the reservations with food caused many bands to leave rather than starve. It was only natural to seek out the encampment of Sitting Bull where these refugees were welcomed and fed. Added to that was Custer's eagerness to corner the massed Indians before they could again disperse – an inevitability due to the constant need for fresh pastures for the horses, and the pursuit of game. What should a society do when confronted with imminent collapse, Philbrick inquires: “The future is never more important than to a people on the verge of a cataclysm...fear of the future can imbue even the most trivial event with overwhelming significance.” Thus, Sitting Bull's visions had a powerful resonance that enhanced his importance as a leader.

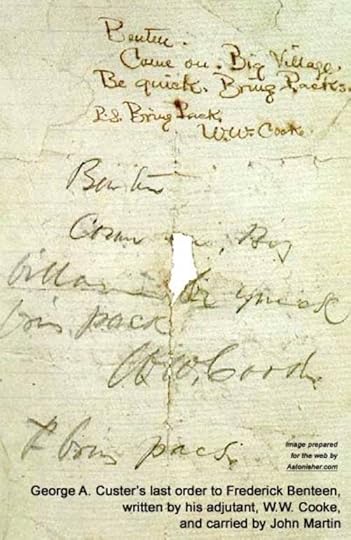

Custer's impulsiveness, flamboyance, and daring have often been blamed for his faulty decisions leading up to the events of June 25. Philbrick examines the question of character more carefully. On the one hand, it was part of his charisma. Common soldiers were inspired by him. His independence from authority and quick-thinking were critical in securing victory for the Union in the Battle of Gettysburg. Even after his death, the 7th Cavalry was said to still reflect the imprint of his “dash.” The same characteristics, however, instilled strong dislikes. Philbrick recounts a dynamic of animosity between Custer and his senior officers. Resentfulness, doubt, the suspicion that Custer's decisions were self-serving rather than prudent, and a reluctance to be targeted by Custer's mercurial emotions all fused in a passive aggressive Capt. Benteen, an alcoholically impaired Capt. Reno, back-biting among the senior officers, and a poorly conceived strategy that ignored the warnings of his own Indian scouts. Nor was Custer's superior, General Terry blameless. With a lawyer's ambiguity, he first instructed Custer to follow a cautious plan, but then added that Custer should use his own judgment if they located the Indians earlier than anticipated. His earlier appointment of Major Reno over Custer to lead a key scouting patrol did little to enhance a spirit of cooperation. Emotion-driven decisions bring this story to life.

It also causes us to reflect: What is the source of personal charisma? Wise decision-making, deep reflection, effective management skills – perhaps all are trumped by the perception of good luck. Do we flock to those whom luck favors, hoping some of that radiance will shower down on us the followers? Custer had charm, but he was also very lucky. At the Little Bighorn, his luck finally ran out.

Philbrick approaches his material to assess the flawed accounts of the events. We should not be surprised to learn that eye-witness accounts can be unreliable. The mind fashions narratives that support opinions of ourselves and others. As these narratives are repeated, we are increasingly persuaded of their accuracy. It is from this vantage point that Philbrick examines what has been said about Custer and the events surrounding the battle – with the wisdom of hindsight. A stray remark could easily have been merely a joke, or a theatrical gesture. Certainly the survivors of that day had reason to cast themselves in the best possible light.

What makes this a book to be enjoyed by the widest possible audience is its superlative writing. He sets up the completely unexpected observation: “Custer did not drink; he didn't have to. His emotional effusions unhinged his judgment in ways that went far beyond alcohol's ability to interfere with clear thinking” (p.17). The most polished comedian could not have done a better job of delivery.

At another point, the uninspired and uncharismatic Major Reno is sent out on a prescribed path by Terry. “Marcus Reno was edging toward a momentous, potentially insubordinate decision. Instead of simply finding, as he later put it, 'where the Indians are not,' why not try to find where they are? Contrary to nearly everyone's expectations – especially General Terry's – Reno decided to do the obvious: find the Indians' trail and follow it” (p.78).

Philbrick's description of a 1200 man outdoor encampment crowded into a protective quadrilateral formation along with horses & mules instills a visceral assault on our senses. Details such as the “grasshoppering” of a steamboat up the river, and the problems of the Springfield single-shot carbine immerse the reader in another time and place. His depiction of characters and their intertwined histories is so vivid that despite the scores of names and roles, the reader retains an individual sense of each of them.

Reading this book did not change my overall opinion of Custer. It did, however, ignite a sense of connection with events I had previously considered to be musty history.

NOTE: I read the hard-cover edition published by Viking and highly recommend it. This is a beautifully made book. Ample maps are distributed throughout the text. Two sections of photographs are printed on heavy, quality stock. In addition to the extensive notes and bibliography, the book is indexed. The cover art shows a vast and cloud-darkened sky. The silhouettes of a company of cavalry rides two abreast across the crest of a hill. We sense they are disappearing into history, not through perspective, but through the composition. The band is grouped with flags unfurled at the head, and trails off to single stragglers at the rear. The whole is framed by a huge low-lying gray ceiling of clouds.