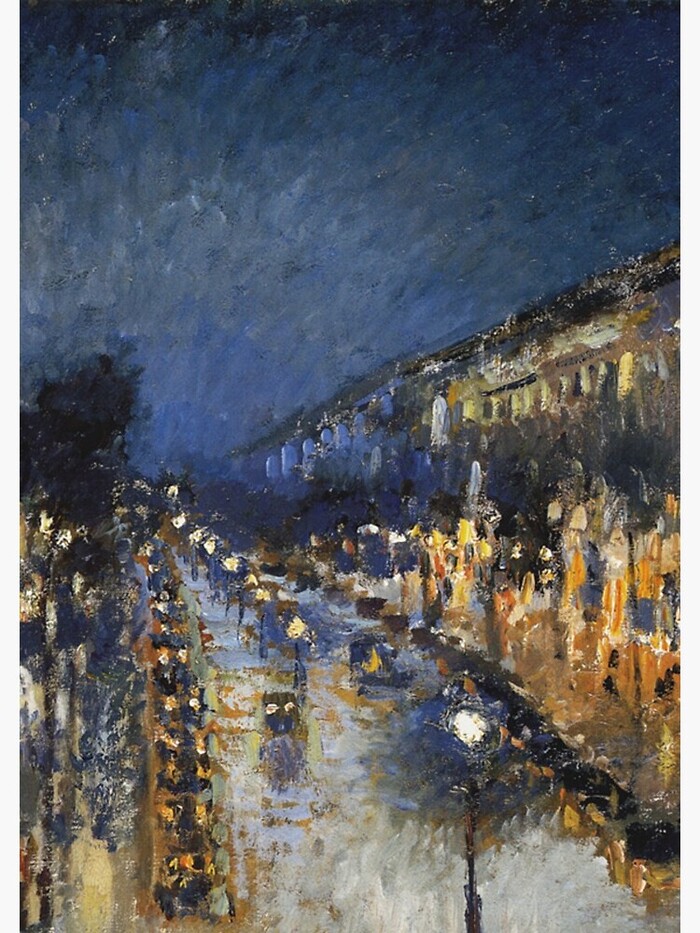

It was Adam Gopnik’s review of this new biography of Camille Pissarro in the New Yorker that persuaded me to read this book. Pissarro, sometimes dubbed the “Father of Impressionism,” is a painter generally well represented in museums showing impressionist paintings. For example, the National Gallery in Washington DC has 12 Pissarro paintings on display. At the same time, Pissarro’s paintings don’t seem to meet the “test of the crowded room” (Gopnik’s term). Guided museum tours and visitors tend to congregate in front of (the usually nearby) paintings by Monet, Manet, Renoir, Cézanne, and Degas (not to speak of Van Gogh). Against this backdrop, I found the book to be very good at two tasks. First, providing an account of why Pissarro holds a central place in the impressionist narrative; and, second, explaining why Pissarro is today not regarded as one of the grandees of the impressionist movement. On the first task, the book documents Pissarro’s major influence on many of the key impressionists and post-impressionists, especially Cézanne. At the same time, Pissarro is portrayed as the quintessential nice family guy among a circle of men (Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt being exceptions) that come across as neither nice nor family-oriented. On the second task, the book convincingly argues that Pissarro’s paintings require much effort and concentration to appreciate, something that is especially out of tune with today’s selfie-based and rapidly-moving museum visitation culture.

The book’s print makes reading it a pleasure; the book also contains a useful collection of Pissarro’s key paintings (in color) as well as photos of Pissarro and his family and fellow painters (in black and white).