What do you think?

Rate this book

336 pages, Mass Market Paperback

First published January 1, 1961

Past Engagements

(A Book Review of Nick Joaquin’s The Woman Who Had Two Navels)

Over damp Hong Kong the day dawned drizzling, astonishing with sunshine the first passengers huddled inside the ferries, luring them out on deck to spread cold fingers in the blond air and to smile excitedly (that night was full moon of the Chinese New Year) at the great rock city coming up across the black water, rising so fat and spongy in the splashing light the waterfront's belt of buildings looked like a cake, with alleys cutting deep into the icing and hordes of rickshaws vanishing like ants between the slices.

"They're both agents of the devil—she and her mother. They work as a team: the mother catches you and plays with you until you're a bloody rag; then she feeds you over to her daughter.... They work for each other. Whenever I was with one of them I could feel the other watching greedily. They share each other's pleasure, watching you twitch. And when they've screwed you up to the breaking point the daughter springs her abominable revelation [of having two navels]—and you go mad and run amuck. And there's one more soul that's damned."

From the ramparts where the Spaniards had watched for Chinese pirate and English buccaneer, the younger taller city beyond the walls seemed rimmed with flame, belted with fire, cupped in a conflagration, for a wind was sweeping the avenue of flametrees below, and the massed treetops, crimson in the hot light, moved in the wind like a track of fire, the red flowers falling so thickly like coals the street itself seemed to be burning.

Macho had suddenly packed up one day and flown off to Manila; not really caring to see the city again or anyone there; not really moved when he saw it, flat and spiky, its bared ribs and twisted limbs a graph of pain in the air; not really astonished even by its vivacity—traffic brimming between the banks of rubble; daylong blocklong queues at the movie houses; the ruins noisy with night clubs; and, on his third night there, like a nightmare's climax, a glittering fashion show in the bullet-pocked ballroom of a gutted hotel, where Macho, turning away from the sequins and diamonds, the shattered ceiling and the bloodstained floor, had so abruptly come face to face with Concha Vidal ...[H]e had suddenly and sharply and exultantly known, with the old ache in the marrow and a blaze of flametrees in the mind, that he had never stopped wanting, he had never stopped desiring this woman.

Behind him now, like smoky flames in the noon sun, the whole beautiful beloved city, the city that he guarded even now, here on this mountain pass, and for which he had come so far away to die—to the edge of the land, into the wilderness, up the cold soggy mountains of the north—and he told himself that, finally, one discovered that one had been fighting, not for a flag or a people, but for just one town, one street, one house; for the sound of a canal in the morning, the look of some roofs in the noon sun, and the fragrance of a certain evening flower.

He told himself that, finally, one found oneself willing to die, not for a great public future, but a small private past; and he picked up his pistol, having finished eating, and crawled back to the cliff's edge.

Opening his eyes he saw, not the stars or pine branches, but the canopy of a bed and the faces of his two sons hovering over him; seeing suddenly in their faces all the years of foreign wandering, the years of exile, but knowing suddenly now that the exile had, after all, been more than a vain gesture, that his task had not ended with that other death in the pinewoods, that he had stood on guard, all these years, as on the mountain pass, while something precious was carried to safety. For there it was now in the faces of his sons—the mountain pass, and the pinewoods, and the shapes of the men who had died there. There it was now in their faces—the Revolution and the Republic, and that small private past for which he had come so far away to die. It had not been lost ... [T]here was no need to cross the sea to find it. Here it was before him (and he strove to rise to salute it) in the faces of his sons. He had saved it and it was now in the present, and the hovering faces brightened and blurred about him, became the sound of a canal in the morning, the look of some roofs in the noon sun, and the fragrance of a certain evening flower. Here he was, home at last ... and before him, like smoky flames in the sunset, the whole beautiful beloved city.

"If you must go down, go down raging. Do not lose that ability, like I did. Take things hard, make a fuss, and refuse to accept what we are—no not even now. Rage, rage against us—even now!"

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

...

And you, my father, there on the sad height,

Curse, bless, me now with your fierce tears, I pray.

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

If you beget a monster of a child it could prove you were rather monstrous yourself.But the story truly begins with Concha Vidal, Connie's flighty mother who's experienced much heartbreak and disillusion throughout each era she experiences. In one of them, she encounters Macho, a younger man who shares her thrill-seeking ways and eventually becomes someone she grows to love. Unfortunately, she's married and he's, well, young. Although her latest husband is one of necessity and they've come to an understanding, Macho and Concha's relationship is frowned upon by society and is the subject of much ridicule among their peers. Concha, not wanting to destroy the boy's life, leaves the country, thus ending their dalliances and breaking his heart. When she returns, she asks him to marry her daughter Connie, in order to obtain the happiness of the two people she cares about most in this world.

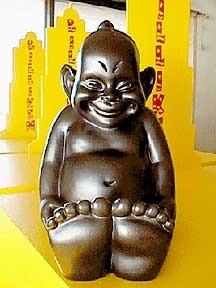

"If your hands were not clean, your good actions had grimmer and more relentless consequences than your sins."Unbeknownst to anyone, Connie has been corrupted by her mother's past and this very decision, which leads the little girl on the path to insanity, for lack of a better word. In one method of coping with this, she makes friends with the hideous, inanimate idol Biliken. Biliken becomes her anchor, a way of shielding her from the harsh realities lurking beyond her safe little bubble.

"But don't you understand, Father? I want to be good. I'm trying to stay good. Does one go mad for trying to do that? Is it that hard?"If this whole thing wasn't a mess already, Connie's narratives get confusing as hell towards the end. The hallucinations she experiences are supposed to show her unstable mental state and how she slowly overcomes her issues, but most of the time I had no clue what was going on or what was really happening. Only until after I had gone through these scenes over and over again for weeks did I finally get that her dreams were in fact dreams.

"It's very hard indeed. But you, Connie, have taken the easiest way out. You are not trying, you have given up... When you convinced yourself you had two navels, you retreated, not from evil, but only from the struggle against evil. People can't be good unless they know they're free to be bad if they wanted to."

“...such formulated "messages" are of less concern to the sensitive reader than the primary source of the novel's beauty: the intense poetry of its language.”

—Josefina D. Constantino, Philippine Studies vol. 9 no. 4

From the ramparts where the Spaniards had watched for Chinese pirate and English buccaneer, the younger taller city beyond the walls seemed rimmed with flame, belted with fire, cupped in a conflagration, for a wind was sweeping the avenue of flametrees below, and the massed treetops, crimson in the hot light, moved in the wind like a track of fire, the red flowers falling so thickly like coals the street itself seemed to be burning…he was trying to piece together, to add up the night, was trying to understand why a series of unrelated doings…should suddenly fuse into a pattern, exploding in his mind (as though flametrees had ignited a bunch of fireworks) in a great burning shower of joy. The sensation so shocked him breathless that, chattering faster and faster, he lapsed at last into mere noise, into a mystic babbling, half stammer and half laughter; his face lifted to the sun and the wind, the blood ablaze on his cheeks and the tears in his eyes. He was young, it was summer, and the flametrees were in bloom. He was young and healthy and happy, and the city lay at his feet.

— pg 66, Macho’s love for Concha blooms (my favorite passage of this book)

Macho, turning away from the sequins and the diamonds, the shattered ceiling and the bloodstained floor, had so abruptly come face to face with Concha Vidal…he had suddenly and sharply and exultantly known, with the old ache in the marrow and a blaze of flametrees in the mind, that he had never stopped wanting, he had never stopped desiring this woman.

—pg 77, Macho and Concha’s love symbolized by flametrees

1) She chooses to live, in spite of her trauma from family betrayal, to live for herself.

2) She chooses to leave her family and the pain they cause, to truly heal

3) She runs away with a man who has a wife and 2 newly-born babies

Then some pig of a girl comes along and breaks up everything we've been trying to preserve—and what do you do? You all rush to her side. You pity her, you help her, you defend her. She's the heroine, she has greatness of spirit. She has you all cheering behind her —yes, even God!

—pg 191, Rita correctly criticizes her author’s book ending

1) Rewrite the ending to address the concerns. Reimagine and massage the ending so that the catharsis can be fully rendered without the baggage of those problems. Have Connie do Step 1 and Step 2 only, or do Step 3 but don’t romanticize it, cast it in the shadowy vibes of moral ambiguity.

2) Simply have audacity. Be aware of those problems in the ending, and commit to it without extended justifications. Prepare for blowback but still stand on business. Have some dignity.