Boats, books and boxing. Steven Heighton's debut combines three of my favorite things. How could it miss?! Young Sevigne Torrins comes from a line of pugilist sailormen, self-taught intellectuals with a love for the Sweet Science (that's punching people in the face). He grows up on the Canadian side of Lake Superior -- the Soo -- boxing and playing literary "name that reference" games with his Hemingway-esque father. After Torrins Sr.'s boozing splits the family apart, Sevigne stays with his dad on the banks of the lake while his mother and older brother start a new life and family in Cairo.

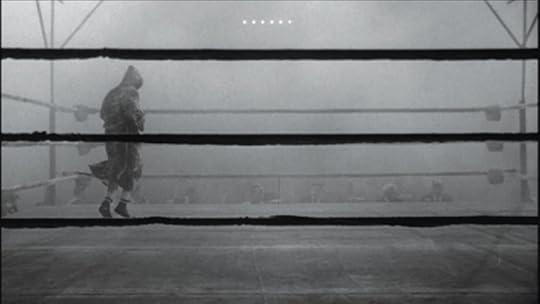

When he's not belting it out in amateur boxing bouts (I thought Canadians just did hockey), Sevigne dreams of becoming a great writer, feverishly dashing off poems to arts publications. No surprise, Heighton also started his literary life as a poet, so he waxes a lot about the search for transcendence or some such jazz. But brother, can the guy write about boxing. Like a boxer himself, Heighton varies his verbal attack, writing in short, choppy, fragmentary jabs, then unleashing a torrent of words in great haymaker paragraphs that run for a page or more.

After his father's death, Sevigne, in his mid-20s, sets out for the big city -- Toronto!!! -- to make his fortune as a novelist. He hooks up with Eddy, a friend from high school, who has big plans to start a radical and revolutionary literary magazine (tho he can't settle on a name for it that's sufficiently radical and revolutionary). Eddy's prone to saying things like "Nobody knows what postmodern means -- that's what's so postmodern about the term!" Eddy gets Sevigne a job writing pithy but shallow capsule reviews of great novels (which is absolutely NOTHING like what I do here on goodreads, just so we're all clear). Sevigne finds the arts scene in Toronto is less about art than catty gossip, fashionable drugs and fashionable fashions, and being seen at all the hippest clubs. Still, hot sex with poet babes can make living with trendoid ayholes tolerable.

I much preferred the first half of "The Shadow Boxer" to the second. The scenes of Sevigne frustratedly watching his father's daily disintegration felt more genuine and honest than his trip to the big city. In the second half of the book, Heighton's prose turns precious, his metaphors labored as Sevigne guzzles down gallons of rye to dull the pain of being artistic or something. Other than its Canadian origin, there's not a lot to set "The Shadow Boxer" dramatically apart from thousands of other wandering-youth novels in the tradition of the Jacks, London and Kerouac. Of course it's pretentious. It's meant to be. Young men aspiring to literary lionhood are supposed to be pretentious. But it's pretentious without being insufferable.

On the face of it, this sounds like a stupid statement, but "The Shadow Boxer" is a book for readers. Not in the sense of "pick up a paperback before a plane trip to kill time for a couple chapters before falling asleep," but for READERS: people with an honest passion about books, who pick apart sentences and peer at the mechanics, who value the power of words and what they can accomplish. It's a book in love with literature and language, at times in opposition to good sense and restraint. It's not exactly a good novel, and parts of it are outright bad, but it works so hard, it's so damn determined to be meaningful, that I couldn't find it in my heart to be cruel to it. It's a poopin-on-the-carpet puppydog of a book by an author who's likely to find something more interesting to say now that he's got this out of his system.