Until a few weeks ago, Sister Carrie wasn’t even on my guilt pile. I was finally moved to pick the book up after seeing that it was at the top of a handwritten “you must read” list by William Faulkner. (A Facebook thing.) Until that time, I think I had always thought, vaguely, but also without reading experience proof, of Theodore Drieser as a dour sour writer from the depressing “Gilded Age.” And, now after the reading, especially after the last 75 pages or so death march of a major character, I guess I wasn’t far off the mark in that assessment. Still, that said, I view Sister Carrie as a first rate novel, an American classic in every sense of the word.

Drieser, it seems, was a great reader first. Hardy, Tolstoy, Balzac, and other masters of realism, were his guides. The influences are obvious, but the synthesis is complete. He was his own writer. Drieser’s artistic balance and eye for psychological detail and nuances were considerable, as displayed in the first remarkable paragraphs of the Sister Carriel, where the reader is first introduced to a young Wisconsin girl, Carrie Meeber, who is on a train, nervously heading toward Chicago.

It was in August, 1889. She was eighteen years or age, bright, timid, and full of the illusions of ignorance and youth. Whatever touch of regret at parting characterized her given up. A gush of tears at her mother's farewell kiss, mill where her father worked by the day, a pathetic sigh as the familiar green environs of the village passed in review and the threads which bound her so lightly to girlhood and home were irretrievably broken.

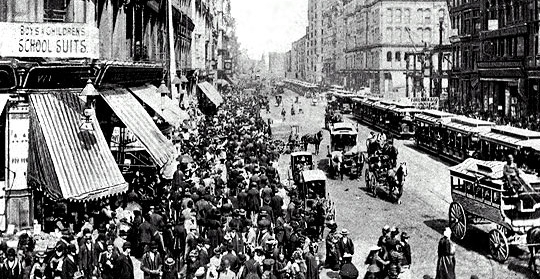

To be sure there was always the next station, where one might descend and return. There was the great city, bound more closely by these very trains which came up daily. Columbia City was not so very far away, even once she was in Chicago. What pray, is a few hours a few hundred miles? She looked at the little slip bearing her sister's address and wondered. She gazed at the green landscape, now passing in swift review until her swifter thoughts replaced its impression with vague conjectures of what Chicago might be.

When a girls leaves her home at eighteen, she does one of two things. Either she falls into saving hands and becomes better, or she rapidly assumes the cosmopolitan standard of virtue and becomes worse. Of an intermediate balance, under the circumstances, there is no possibility. The city has its cunning wiles, no less than the infinitely smaller and more human tempter. There are large forces which allure with all the soul fullness of expression possible in the most cultured human. The gleam of a thousand lights is often as effective as the persuasive light in a wooing and fascinating eye. Half the undoing of the unsophisticated and natural mind is accomplished by forces wholly superhuman. A blare of to the astonished scenes in equivocal terms. Without a counselor at hand to whisper cautious interpretation what falsehoods may not these things breathe into the unguarded ear! Unrecognized for what they are, their beauty, like music, too often relaxes, then wakens, then perverts the simpler human perceptions.

Caroline, or Sister Carrie, as she had been half affectionately termed by the family, was possessed of a mind rudimentary in its power of observation and analysis. Self-interest with her was high, but not strong. It was nevertheless, her guiding characteristic. Warm with the fancies of youth, pretty with the insipid prettiness of the formative period, possessed of a figure promising eventual shapeliness and an eye alight with certain native intelligence she was a fair example of the middle American class two generations removed from the emigrant. Books were beyond her interest knowledge a sealed book. In the intuitive graces she was still crude. She could scarcely toss her head gracefully. Her hands were almost ineffectual. The feet, though small were set flatly. And yet she was interested in her charms, quick to understand the keener pleasures of life, ambitious to gain in material things. A half-equipped little knight she was, venturing to reconnoiter the mysterious city and dreaming wild dreams of some vague, far-off supremacy, which should make it prey and subject the proper penitent, groveling at a women's slipper.

Everything you need to know about Carrie, along with Drieser’s sense of what Art should be, is contained in these paragraphs. Carrie is a very real person, but Drieser, especially as the novel progresses also uses her as vehicle for his own thoughts on Naturalism or Realism (don’t get me started on THAT). This natural sense of self, uncluttered by romantic notions, will eventually be the source of Carrie’s power as an actress. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

In the very next lines, Carrie meets the drummer (sales man), Charles Drouet, a good looking, generally kind , but also selfish man who loves the girls. A dude. He flirts with Carrie, gets nowhere, but is able to give her his card, and get her address. That exchange of information will become useful shortly.

Carrie is met at the station by her sister, who takes her home. Carrie will live with her sister and brother-in-law while she gets herself established. But Carrie has no experience, and she’s not the most practical of girls. She gets off on the wrong foot with her sister and brother-in-law by wanting to go see a show at the theater. (Not nose-to-grindstone enough for those two pinched people.) She also takes a poorly paying, and physically demanding, job at a factory. She immediately starts thinking of Drouet. Carrie soon gets sick, loses her job, but also encounters Drouet, who basically takes her away to live with him (which must have been fairly daring at the time). Drouet is good to Carrie, giving her a place to live, and clothes to wear. What he won’t do is marry her. He keeps delaying this step, while at the same time introducing her to others as his “wife.” Carrie craves this one social anchor, and some resentment toward Drouet soon forms.

Drouet eventually introduces Carrie to G.W. Hurstwood (“George”), the manager of a prestigious Chicago bar. As a character, Hurstwood comes close to being the central character of the novel. He’s not very likable. Manipulative, bored with his home life, and well paid for not doing much, he initially strikes the reader as something of a predator. Hurstwood is basically an old bartender who made out. His employers trust him, and the high end bar he runs basically runs itself. His home life has grown static, as both his wife and kids look to him for money and little else. By the time Carrie comes along, Hurstwood, who is about 40, and seemingly buttoned down, is ready for some Middle Age Crazy. Carrie does intrigue him, and he nibbles and flirts around the edges of Drouet and Carrie’s relationship. What pushes it over the edge is an unforeseen opportunity for Carrie.

Drouet is a member of the Elk Club. The club, in a fund raising effort, needs an actress for an amateur production of a play. Unexpectedly, Carrie stands out, and powerfully. This is probably the weakest device in the novel. Dreiser would have us believe that Carrie is a natural at acting. Fair enough. But the rave, Jesus-on-the-Mount responses of the audience, not to mention Hurstwood’s throw-it-all to the wind decision, seem improbable. But this weakness is well cloaked in the characters he has already established, so it is totally believable that both Hurstwood and Drouet are seeing Carrie the person and not Carrie the pretty object for the first time. On that level, the performance, and the reactions it produces, is, I suppose, believable.

What follows is a love triangle, with the dim Drouet finally figuring out that something is going on. The not-so-dim Mrs. Hurstwood also figures out George has been up to something (though by modern day standards, it’s pretty mild stuff). It all quickly falls to ashes for Hurstwood, and he makes a bad decision involving $10,000 of bar money, and , via some artful lies, he essentially kidnaps Carrie and flees Chicago. A reluctant Carrie eventually settles for this arrangement, while finally exacting an exchange of wedding vows with Hurstwood. Curiously, Carrie never asks about whether Hurstwood is committing bigamy. I wondered, at the time, if this would be some sort of dark turn for Carrie’s character. Not so. For the next few years, the couple make a go of it in New York, with Hurstwood managing a bar – though it’s not the cushy arrangement he once had.

Eventually, that too falls apart, and Hurstwood loses his stake in the enterprise. Hurstwood and Carrie are now caught in a downward spiral, and Hurstwood is unwilling to work at jobs he considers beneath him. The one go-to, bar tending, he simply dismisses. Carrie however, via a pretty neighbor, meets Bob Ames, a scholar from Indiana (and probably an authorial stand-in for Dreiser). Ames is no phony, and his few comments regarding art and the theater, light a fire in Carrie. After the disappointments of life with Drouet and Hurstwood, Ames represents a truth and beauty that Carrie had, up until this point, only vaguely sensed. A sharper focus has now been provided. With it, Carrie tries to break in to acting. She eventually is able to land a job as a chorus girl, and it’s not long before she is recognized, and elevated. A star is born.

Meanwhile Hurstwood continues to goes downhill, and that process accelerates when Carrie finally leaves him. Drieser’s brick by brick dismantling of Hurstwood is one of the most thorough in literature. He’s one of those characters that at one point, earlier on, you want to see get some payback. Oh, he does, and more. You would have to have a heart of stone to be pulling against him by novel’s end. But Dreiser’s critique here is social – and inexorable. It’s not a matter of pulling for good guys or bad guys, it’s just reality of the late 19th Century American kind. There’s a poignant counterpoint toward the end of the story, that Dreiser frames beautifully. Carrie, in her high and luxurious tower, is trying to keep her connection with the natural world by reading Balzac (per Ames suggestion), while her former “husband” is struggling to survive in the mean streets below. One is doomed, and the other occupies a glittering, but also brittle and fragile world. One added irony, that goes beyond the boundaries of the novel, is that the actress Dreiser probably modeled Carrie after, Middie Maddern Fiske, would also die in poverty.