In just over 200 pages, Greer provides us with a more or less universal history of what he calls the Apocalypse meme. This was first published in 2012, no doubt to counter the then current and virulent version of the meme predicting the end of time and civilisation on Friday 21 December 2012, as anticipated by the ancient Mayans’ calendar. As we know, the end did not come as predicted.

Greer’s intention here is to tell the story of how this meme started, and how it has been used, adapted and reissued over and over again (always with the same “disappointing” outcome) throughout the centuries.

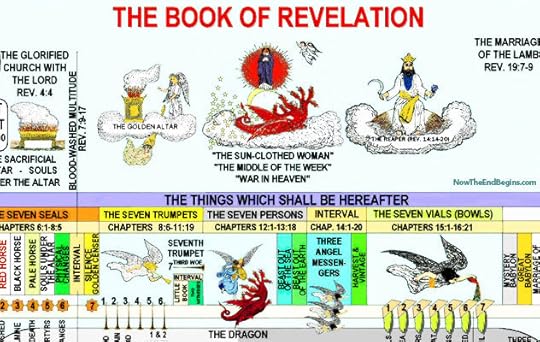

To the best of our knowledge, the meme’s first articulation stems from the teachings of Zoroaster, probably as early as the 12th-c BCE, and incorporated as an essential part of Zoroastrianism. (Remnants of the Zoroastrians are to found in the Parsees of today.) Zoroastrianism taught that there was a good god (Ahura Mazda) and an evil one (Angra Mainyu), and that the battles between these two would rage over great lengths of time until a final, apocalyptic battle would solve the matter in favour of Ahura Mazda. Thus the meme was born… Greer traces its history through time, and the various manifestations of the meme up to and including the present day; and suggests that versions of it will continue to manifest itself in our history into the future, and suggesting that each time it occurs, the same “disappointment” will result.

Greer is more interested in tracing specific events connected with the meme rather than trying to psychoanalyse or philosophise on the matter — possibly because the issue is fraught with the difficulties we associate with all attempts to deal with the problem of good and evil in our lives. For me, the core issues are two: the dissatisfaction with our lives on earth, and a conceptual error in determining “good” and “evil” as separate, independent and all powerful, antagonistic forces. Our dissatisfaction with our lives is a result of the perpetual warring between these two entities. The “hope” implied in the meme lies in the promise that, in the end, the “good” will win over completely, and then we will all be happy and satisfied with everything.

The “obvious” answer lies in the fact that “good” and “evil” are not absolute at all, but relative. Few of us want to accept that. We all “know” what is good, and what is evil, and we base our morality and our ethics by adopting the battle-lines set by the meme so that we insist on fighting for the good, and battling against evil. The irony, of course, is that this approach ensures that the power of the meme is intensified, not mitigated; and that in turn leads to fear, stress, perpetual war, and ultimately, even to despair. It will appear that the only way we might find perfect happiness is only when we are dead!

That last sentence needs to be contextualised as a further example of the meme, especially when it comes to religions which posit that yes, indeed, it is only when you are dead that you might find perfect happiness (provided you follow specific dictates of the particular religion involved… — otherwise, only perpetual horror and damnation await you!). This “spiritual” can also be attributed to Zoroastrianism — albeit a heretical version of it perpetrated by the Zoroastrian monk Mani, who taught that only “spirit” was absolutely good, and that all matter was, by definition, absolutely evil. This Manichaean interpretation, while “officially” condemned, has been absorbed by all religious groups, cults and sects, and can even be identified in secular, cultural, social, economic, ideological and political organisations, but manifested in myriad ways peculiar to each. They are all trapped within the same fallacious meme.

The above are but some of the thoughts that can be explored in dealing with this subject. They are not necessarily included in Greer’s work, but they can be extrapolated from it to a certain extent.

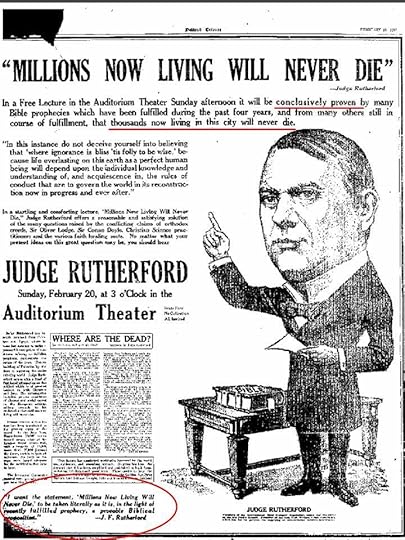

Greer’s book is a good, basic history which should be read by all. It is written in a very accessible, readable style, so it does not require much effort on the part of the reader. Its basic information should, by now, have been absorbed by everyone. Unfortunately, the reality is that, especially in a world where religion, superstition and so-called spiritual cult beliefs are apparently on the rise, people will still be primed to accept the next false prophet at face value, and so the meme will persist. (At the end of the book, Greer — in keeping with his avowed interests — argues that the Apocalypse meme has no place in an “authentic spirituality”. Personally, I think the problem here is in the word “spirituality” (authentic or not), as it carries too much cultural baggage to be of any real value any more.)

Hopefully, this book will assist in defusing the power and potential negative influences of the meme in all its manifestations, so that it can be safely ensconced in history and no longer emerge to fool and frighten us ever again.