What do you think?

Rate this book

Unknown Binding

First published January 1, 1974

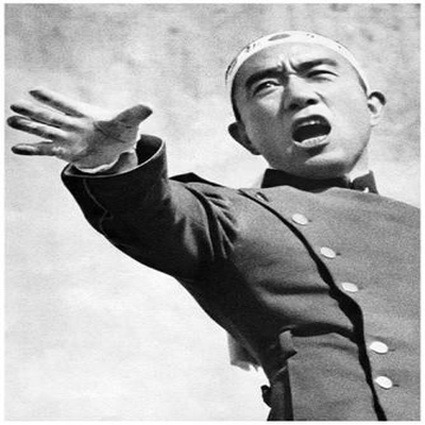

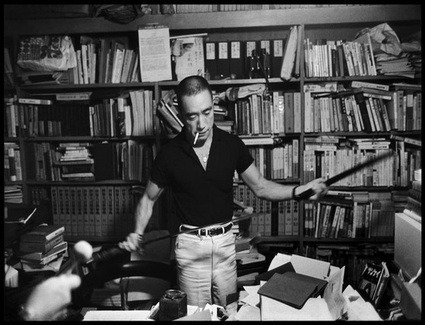

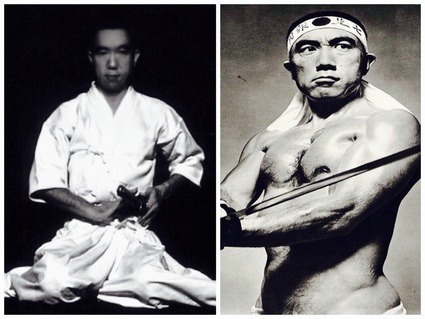

traces the life of this tortured, nearly superhuman personality. Mishima survived a grotesque childhood, and subsequently his sadomasochistic impulses became manifest - as did an increasing obsession with death as the supreme beauty. Nathan, who knew Mishima professionally and personally, interviewed family, colleagues, and friends to unmask the various - often seemingly contradictory - personae of the genius who felt called by "a glittering destiny no ordinary man would be permitted." (back cover)