What do you think?

Rate this book

256 pages, Paperback

First published January 1, 1893

It is a wild tract full of sudden falls, unexpected rises, precipitous dislocations. The high and the low are met together. The big and the little alternate in a rapid and illogical succession. Its perilous trails are followed successfully by but few — by a lineman, perhaps, who is balanced on a cornice, by a roofer astride some dizzy gable, by a youth here and there whose early apprehension of the main chance and the multiplication table has stood him in good stead. This country is a treeless country — if we overlook the " forest of chimneys " comprised in a bird's-eye view of any great city, and if we are unable to detect any botanical analogies in the lofty articulated iron funnels whose ramifying cables reach out wherever they can, to fasten wherever they may. It is a shrubless country — if we give no heed to the gnarled carpentry of the awkward frame-works which carry the telegraph, and which are set askew on such dizzy corners as the course of the wires may compel. It is an arid country — if we overlook the numberless tanks that squat on the high angles of alley walls, or if we fail to see the little pools of tar and gravel that ooze and shimmer in the summer sun on the roofs of old-fashioned buildings of the humbler sort. It is an airless country — if by air we mean the mere combination of oxygen and nitrogen which is commonly indicated by that name. For here the medium of sight, sound, light, and life becomes largely carbonaceous, and the remoter peaks of this mighty yet unprepossessing landscape loom up grandly, but vaguely, through swathing mists of coal-smoke.

From such conditions as these — along with the Tacoma, the Monadnock, and a great host of other modern monsters — towers the Clifton. From the beer-hall in its basement to the barber-shop just under its roof the Clifton stands full eighteen stories tall. Its hundreds of windows glitter with multitudinous letterings in gold and in silver, and on summer afternoons its awnings flutter score on score in the tepid breezes that sometimes come up from Indiana. Four ladder-like constructions which rise skyward stage by stage promote the agility of the clambering hordes that swarm within it, and ten elevators — devices unknown to the real, aboriginal inhabitants — ameliorate the daily cliff-climbing for the frail of physique and the pressed for time.

The tribe inhabiting the Clifton is large and rather heterogeneous. All told, it numbers about four thousand souls. It includes bankers, capitalists, lawyers, "promoters"; brokers in bonds, stocks, pork, oil, mortgages; real-estate people and railroad people and insurance people — life, fire, marine, accident; a host of principals, agents, middlemen, clerks, cashiers, stenographers, and errand-boys; and the necessary force of engineers, janitors, scrub-women, and elevator-hands.

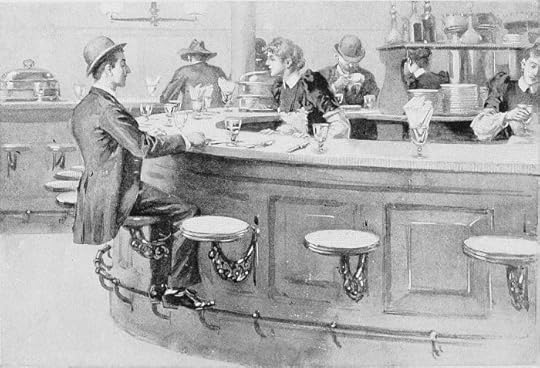

All these thousands gather daily around their own great camp-fire. This fire heats the four big boilers under the pavement of the court which lies just behind, and it sends aloft a vast plume of smoke to mingle with those of other like communities that are settled round about. These same thousands may also gather in installments — at their tribal feast, for the Clifton has its own lunch-counter just off one corner of the grand court, as well as a restaurant several floors higher up. The members of the tribe may also smoke the pipe of peace among themselves whenever so minded, for the Clifton has its own cigar-stand just within the principal entrance. Newspapers and periodicals, too, are sold at the same place. The warriors may also communicate their messages, hostile or friendly, to chiefs more or less remote ; for there is a telegraph office in the corridor and a squad of messenger- boys in wait close by.

In a word, the Clifton aims to be complete within itself, and it will be unnecessary for us to go afield either far or frequently during the present simple succession of brief episodes in the lives of the Cliff-dwellers.

A clear day came ; he conducted them up to the roof-observatory and showed them the city, and they numbered the towers thereof.

The old people tiptoed gingerly around the parapet, while Ogden waved his hand over the prospect — the mouth of the river with its elevators and its sprawling miles of railway track; the weakish blue of the lake, with the coming and going of schooners and propellers, and the "cribs" that stood on the faint horizon — "that's where our water comes from," George explained; the tower of the water-works itself, and the dull and distant green of Lincoln Park ; the towering bulk of other great sky-scrapers and the grimy spindling of a thousand surrounding chimneys; the lumber-laden brigs that were tugged slowly through the drawbridges, while long strings of drays and buggies and street-cars accumulated during the wait. (211)

Ogden smiled. He saw that he was face to face with a true daughter of the West; she had never seen him before, and she might never see him again, yet she was talking to him with perfect friendliness and confidence. Equally, he was sure, was she a true daughter of Chicago; she had the one infallible local trait — she would rather talk to a stranger about her own town than about any other subject.

George felt his heart give an indignant throb. He seemed to see before him the spokesman of a community where prosperity had drugged patriotism into unconsciousness, and where the bare scaffoldings of materialism felt themselves quite independent of the graces and draperies of culture. It seemed hardly possible that one short month could make his native New England appear so small, so provincial, so left-behind.

"You've got to have snap, go. You've got to have a big new country behind you. How much do you suppose people in Iowa and Kansas and Minnesota think about Down East? Not a great deal. It's Chicago they're looking to. This town looms up before them and shuts out Boston and New York and the whole seaboard from the sight and the thoughts of the West and the Northwest and the New Northwest and the Far West and all the other Wests yet to be invented. They read our papers, they come here to buy and to enjoy themselves." He turned his thumb towards the ceiling, and gave it an upward thrust that sent it through the six ceilings above it. " If you'd go up on our roof and hear them talking — "

" Oh, well," said George ; " hadn't we better get something to eat?"

" And what kind of a town is it that's wanted," pursued McDowell, as he pulled down the cover of his desk, " to take up a big national enterprise and put it through with a rush? A big town, of course, but one that has grown big so fast that it hasn't had time to grow old. One with lots of youth and plenty of momentum. Young enough to be confident and enthusiastic, and to have no cliques and sets full of bickerings and jealousies. A town that will all pull one way. What's New York ?" he asked, flourishing his towel from the corner where the wash-stand stood. " It ain't a city at all; it's like London — it's a province. Father Knickerbocker is too old, and too big and logy, and too all-fired selfish. We are the people, right here..." (88-89)

During the enforced leisure of his first weeks he had gone several times to the City Hall, and had ascended in the elevator to the reading-room of the public library. On one of these occasions a heavy and sudden down-pour had filled the room with readers and had closed all the windows. The down-pour without seemed but a trifle compared with the confused cataract of conflicting nationalities within, and the fumes of incense that the united throng caused to rise upon the altar of learning stunned him with a sudden and sickening surprise — the bogs of Kilkenny, the dung-heaps of the Black Forest, the miry ways of Transylvania and Little Russia had all contributed to it.

The universal brotherhood of man appeared before him, and it smelt of mortality — no partial, exclusive mortality, but a mortality comprehensive, universal, condensed and averaged up from the grand totality of items.

In a human maelstrom, of which such a scene was but a simple transitory eddy, it was grateful to regain one's bearings in some degree, and to get an opportunity for meeting one or two familiar drops. (55-56)

"Oh, well," began George, with the air proper to a launching out into a broad and easy generalization, " aren't we New England Puritans the cream of the Anglo-Saxon race ? And why does the Anglo-Saxon race rule the globe except because the individual Anglo-Saxon can rule himself?" (225)

"Why are things so horrible in this country?" demanded Mrs. Floyd, plaintively.

"Because there's no standard of manners — no resident country gentry to provide it. Our own rank country folks have never had such a check, and this horrible rout of foreign peasantry has just escaped from it. What little culture we have in the country generally we find principally in a few large cities, and they have become so large that the small element that works for a bettering is completely swamped."

He looked almost pityingly on his brother. "This is no town for a gentleman," he felt obliged to acknowledge. "What an awful thing," he admitted further, " to have only one life to live, and to be obliged to live it in such a place as this!" (237-238)

Occasionally it did dry up and stay so for several weeks. Then, on bright Sunday afternoons, folly and credulity, in the shape of young married couples who knew nothing about real estate, but who vaguely understood that it was a "good investment," would come out and would go over the ground — or try to. They were welcomed with a cynical effrontery by the young fellow whom McDowell paid fifty dollars a month to hold the office there. He had an insinuating manner, and frequently sold a lot with the open effect of perpetrating a good joke.

McDowell sometimes joked about his customers, but never about his lands. He shed upon them the transfiguring light of the imagination, which is so useful and necessary in the environs of Chicago. Land generally — that is, subdivided and recorded land — he regarded as a serious thing, if not indeed as a high and holy thing, and his view of his own landed possessions — mortgaged though they might be, and so partly unpaid for — was not only serious but idealistic. He was able to ignore the pools whose rising and falling befouled the supports of his sidewalks with a green slime ; and the tufts of reeds and rushes which appeared here and there spread themselves out before his gaze in the similitude of a turfy lawn. He was a poet — as every real-estate man should be. (104)

He had reached the point where he felt it would be a relief to cut away from town and everything in it ... only so many miles of flimsy and shabby shanties and back views of sheds and stables; of grimy, cindered switch-yards, with the long flanks of freight-houses and interminable strings of loaded or empty cars; of dingy viaducts and groggy lamp-posts and dilapidated fences whose scanty remains called to remembrance lotions and tonics that had long passed their vogue; of groups of Sunday loungers before saloons, and gangs of unclassifiable foreigners picking up bits of coal along the tracks ; of muddy crossings over roads whose bordering ditches were filled with flocks of geese; of wide prairies cut up by endless tracks, dotted with pools of water, and rustling with the dead grasses of last summer; then suburbs new and old — some in the fresh promise of sidewalks and trees and nothing else, others unkempt, shabby, gone to seed ; then a high passage over a marshy plain, a range of low wooded hills, emancipation from the dubious body known as the Cook County Commissioners — and Hinsdale. (176-177)

The spring trailed along slowly, with all its discomforts of latitude and locality, and then came the long, fresh evenings of early June, when domesticity brings out its rugs and druggets, and invites its friends and neighbors to sit with it on its front steps. The Brainards had these appendages to local housekeeping — lingering reminders of a quick growth from village to city. Theirs was a large rug made of two breadths of Brussels carpeting and surrounded on all four sides with a narrow border of pink and blue flowers on a moss-colored background. This rug covered the greater part of the long flight of lime-stone steps. In the beautiful coolness of these fresh June evenings Abbie frequently sat there on the topmost step, under the jig-saw lace-work of the balcony-like canopy over the front door, while her mother occupied a carpet camp-chair within the vestibule and languidly allowed the long twilight to overtake her neglected chess-board. (186)

" Can it be that there are really any such expectations here as these?" He addressed Fairchild exclusively — the oldest and most sedate of the circle.

"Why not?" returned Fairchild. "Does it seem unreasonable that the State which produced the two greatest figures of the greatest epoch in our history, and which has done most within the last ten years to check alien excesses and un-American ideas, should also be the State to give the country the final blend of the American character and its ultimate metropolis ?"

"And you personally — is this your own belief ?"

Fairchild leaned back his fine old head on the padded top of his chair and looked at his questioner with the kind of pity that has a faint tinge of weariness. His wife sat beside him silent, but with her hand on his, and when he answered she pressed it meaningly; for to the Chicagoan — even the middle-aged female Chicagoan — the name of the town, in its formal, ceremonial use, has a power that no other word in the language quite possesses. It is a shibboleth, as regards its pronunciation ; it is a trumpet-call, as regards its effect. It has all the electrifying and unifying power of a college yell.

"Chicago is Chicago," he said. "It is the belief of all of us. It is inevitable; nothing can stop us now." (248-249)