What do you think?

Rate this book

374 pages, Kindle Edition

First published January 1, 2007

Translating from Chinese to English, there are three options when it comes to the name of our protagonist, 繁花:

Naturalise: find an English name that has some degree of overlap with the original — “Florence”, for example

Translate: convey the literal meaning of the name — “Blooming Flowers”, let’s say

Transliterate: render the name phonetically in pinyin — “Fanhua”

Choose “Florence”, and the juxtaposition of English names against the Chinese setting soon becomes jarring. Unless, that is, you keep going and naturalise the place names, brand names, cultural references, and very quickly find you have strayed beyond the remit of translation. You also the burden the reader with the task of detaching the character from all the irrelevant associations that the name will evoke for them — the remnants left in their subconscious by every other Florence they have ever encountered. And surely no reader would be able to put up with “Blooming Flowers” — grating, clunky, and shot through with dehumanising Orientalism — for more than a page or two.

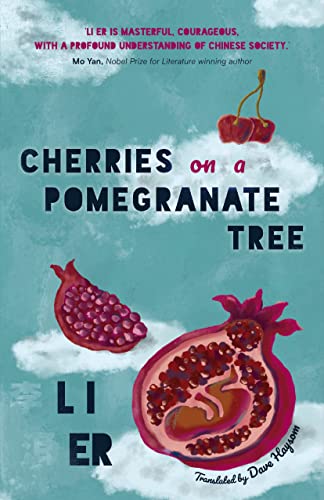

“Fanhua” is the least bad option, but transliteration results in a meaningful alteration to the reader’s experience of the book, especially a book with as many characters as Cherries on a Pomegranate Tree: the cognitive burden of keeping track of all the characters is significantly higher when their names are semantically empty shells.

Sinoist Books is a UK-based independent press that publishes only the best in translated Chinese literature and contemporary fiction. Our mission is to act as a bridge between the Chinese and English-speaking worlds, so that the best Sinophone authors and their works can transcend the language barrier. We believe that literature is a summation of the struggles, aspirations and ideals of the authors, and only by appreciating them can we truly achieve a deeper level of understanding.

We partner with award-winning translators and maintain the highest editorial and design standards in order to ensure that these titles are presented in their best possible light. We pair these titles with energetic marketing and events campaigns in order to introduce English readers to these gems of Chinese literature and culture.