[7/10]

A haunting and disturbing story, skillfully presented, but I hold Mr. Llosa to higher standards after including his sprawling, philosophical War Of The End of The World on my favorites list. I learned a lot now about modern Peru, which is why I picked the book up in the first place, but I also had issues with the muddled dialogue, with the slow pace, continually fragmented by flashbacks, and with a perceived bias against the Sendero Luminoso guerilla, who received an extremely harsh treatment as brainless, blood crazed terrorists.

I have seen a review on the net calling the book a Latin American version of Heart of Darkness , where instead of horizontal movement along an equatorial river, we get a vertical movement into the high Cordillera (Richard Eder). The comparison feels appropriate, due to the prevailing downbeat mood, the permanent danger and the soul crushing climate and isolation. Another connection can be made to the noir books, as the main plot deals with an investigation of three deaths / disparritions, and a secondary plot is a love story of a couple on the run from the local mafia (reminding me of James M Cain in particular).

The setting is Naccos, a semi abandoned, dirt-poor high altitude village consisting of a highway labour camp, a police post and a cantina for getting drunk after work. A sergeant (Lituma) and an Adjutant (Carreno) try to unravel the mystery surrounding three missing persons : a mute simpleton (Pedrito Tinoco) , an albino (Casimiro Huarcaya) and a team foreman (Medardo Llantac) . As we learn about their identities and backstories through flashbacks, the only apparent connections are the fact that they were all strangers for the local population, and they all had suffered grievously at the hand of the serruchos : the blood thirsty Maoist rebels who control the region and who could descend on Naccos at any moment. As if the stories of these three missing unfortunates were not enough, Llosa includes a couple more high profile atrocities commited by the serruchos against foreign tourists and against an environmental activist, which prompted me to suspect the novel is being used to vent the author's dissatisfaction with a government report he helped write on the reconciliation between the different factions in the civil war.

Coming back to the two policemen, they are linked by their lowland origins which makes them also outsiders among the imposing peaks and freezing nights of the Andes. The threat of a serrucho attack that they would be unable to resist hangs like Damocles sword over every moment of their stay in Naccos. Their only recurse is to turn their backs on the world and hold endless conversations in their dismal shack, which frankly makes an already glum novel even less appealing. Llosa experimental technique with dialogue, where he mixes up past and present from one line to another is not helping things along very much. It often feels like the two cops are holding a contest about who is the most depressed:

He took drag after drag on his cigarette, and his mood changed from anger to demoralized gloom. - Lituma.

I've never been so miserable in my life as I was here. - Carreno.

and an exchange between the two:

- I was tired of living. At least that's what I thought, Corporal. But seeing how scared I am now, I guess I don't want to die after all.

- Only a damn fool wants to die before his time, asserted Lituma. There are some fantastic things in this life, though you won't find any around here. Did you really want to die? Can I ask why, when you're so young?

- What else could it be?

- Some sweet little dame must have broken your heart.

Some of the local details that give the novel its authentic flavour and kept me interested in the plot:

- vicunas are a smaller version of llamas, living in the wild at high altitude, very shy animals whose fur is greatly appreciated in luxury clothing, and who are listed as endangered species.

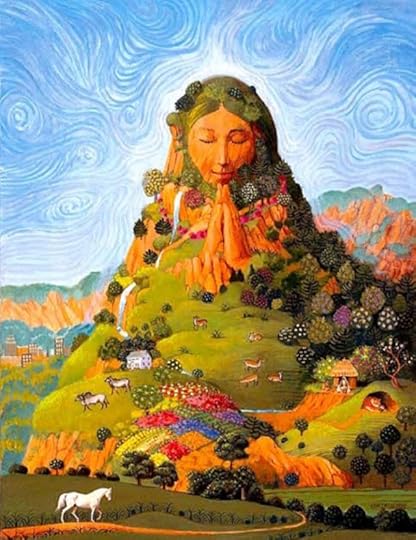

- apu are ancestral mountain spirits, their essence can get incarnated in condors, and they are often malefic

- huaycos are devastating rockslides, send by angry apus according to the locals, probably caused by earthquakes to the scientific mind;

- [edit] serruchos - are the local population, speaking in quechua dialect, the remnants of tribes older even than the Incas. ( You have to understand their thinking. For them, there were no natural catastrophes. Everything was decided by a higher power that had to be won over with sacrifices )

- pishtacos are the Peruvian version of vampires, feeding on human fat instead of blood, and using a dust made of powdered bones in order to put a glamour on their victims

- mukis are a sort of gnomes hiding in the deep mines and scaring the workers

- pisco is a distilate from wine, specific to Peru, and the drink of choice in Dionisio bodega.

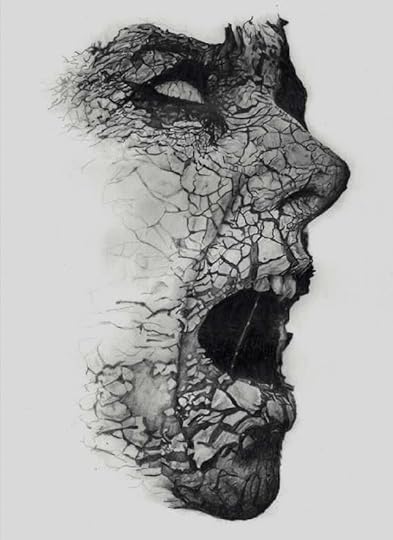

Which brings me to the most interesting aspect of the book for me: the mystical component, the primeval myths and traditions that can be traced back to the stone age and illustrate peculiar similarities across continents. In our case, Dionisyio the barman is a clear reference to Bachus, and his witchy consort Dona Adriana is a maenad - one of the god's followers, achieving ecstasy through drink, dance and debauchery:

When we're dancing and drinking, there are no Indians, no mestizos, no rich or poor, no men or women. The differences are wiped away and we become as spirits.

Later new references are introduced to the bachanalia mysteries, secret practices reserved for the women and translated to preconquista cultures in the Lord of the Fiesta tradition: choosing a person to rule the festivities for one year:

He did some hard drinking, he played the charango or the quena or the harp or the tijeras or whatever instrument he knew, and he danced, stamping his heels and singing, day and night, until he drove out sorrow, until he could forget and not feel anything and give his life willingly and without fear. Only the women went out to hunt him on the last night of the fiesta

Whether these mysteries had anything to do with the disappearances, or if there are even older myths hiding in the heart of the Andes, is for Lituma to uncover and for the reader to wait until the last page.

I will close with my earlier reference to a 'noirish' love story. Llosa chooses to finish this plot line in an unconventional way, but I felt it was appropriate in underlining how the key to the story may be neither with Lituma's cynical atitude nor with Dionisio's escape into drink, but with the young adjutant's naive belief in a better world.