Yaroslav Trofimov was in Kabul when it fell to the Taliban in 2021, and he was in Kyiv when the Russians invaded less than a year later. He told National Review that he wondered if President Zelensky would abandon Ukraine just as President Karzai did Afghanistan. Instead, Zelensky stood his ground: “His courage in that moment saved Ukraine. Lots of Ukrainians don’t necessarily like Zelensky. But this is not a fight for Zelensky. It’s a fight for Ukraine. It’s a fight to hang on to independence.”

Trofimov’s debut novel “No Country for Love,” a work of historical fiction spanning twenty traumatic years in Ukraine’s history, is at once a love letter to his people and a tribute to his family. Trofimov, born into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) and now an Italian citizen serving as chief foreign correspondent for the Wall Street Journal, reminds us that a nation is neither a meme nor a talking point, neither a villain nor a hero. A nation is those who find a way to survive together.

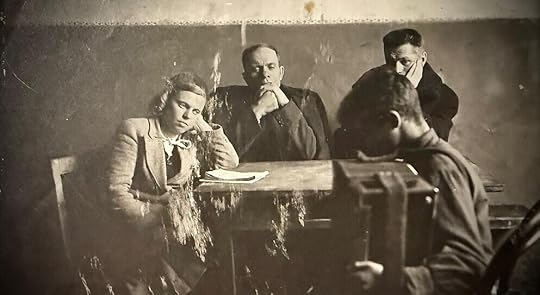

I experienced “No Country for Love” as six fictionalized biographies folded together. First and foremost is that of seventeen-year-old Deborah Rosenbaum, a vibrant Jewish-Ukrainian woman modeled, as Trofimov told Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, on his grandmother Debora: “At the risk of revealing the plot and creating a spoiler, the key pivots in the narrative are true. The characters are true. I took some liberties because some of the actions in the book are things she wished she had done but didn't do.”

This is Trofimov’s way of preserving his grandmother’s story, and he opens that story with an act of violence in 1953 before flashing back to 1930 and the rosy dawn of the brand-new Ukrainian SSR. With centuries of Tsarist repression at an end, Deborah believes passionately in the new order of Soviet self-determination, equality, comradeship, and love. But as Stalinist screws tighten and Nazi thunderclouds gather, as Holocaust follows Holodomor, as flames rage from Kyiv to Kharkiv to Stalingrad, she finds that Ukraine is a country where love is what you sacrifice to live.

The novel’s second biography is, of course, that of Ukraine itself. Trofimov recognizes that his modern homeland is a patchwork quilt stitched together from scraps of Austria-Hungary and Poland, the cosmopolitan core of Kyivan Rus', the conquered Tatars of Crimea, and the eastern marches of Kharkiv and the Donbas. Yet despite Muscovite dogma, despite tsars and Soviets and the neo-tsardom of Putin’s Russia, Ukrainians have always known themselves to be a people unto themselves. That knowledge is tested as Bolshevik winds soon shift from Ukrainization back to Russification.

Deborah herself must survive by drowning her identity beneath Russian waves, reflecting the third biography: that of Ukraine’s Jews who, like her, learn to lie low in a world gone mad. Because this is Deborah’s story and not a tale of the Holocaust itself, the horror of German occupation plays only a supporting if devastating role in her character’s arc. But whether caught behind enemy lines or fleeing deep into Russia, Jews suffered from Ukrainians eager to rat them out and from Russians who blamed them for provoking Hitler. Despite it all, the modern-day President Zelensky’s Jewish heritage speaks to the determination of Abraham’s children to persist within a Ukrainian Babylon.

Of the many tragedies that befell Ukraine’s Jews, one I hadn’t known is that Kyivan Jews didn’t need to die. Moscow’s propaganda machine was so untrustworthy that Jews simply didn’t believe what their own government told them about Nazi atrocities. As Deborah’s father Gersh says, “This whole place is built on lies.” Tens of thousands of Kyiv’s Jews failed to escape envelopment, were rounded up, and died in the ravine of Babyn Yar as a direct consequence of their mistrust of Moscow’s policy of disinformation. This leads me to the fourth biography, and to the long shadow of Joseph Stalin.

Stalin’s consolidation of Party power in 1928-29, his terrors and purges, his omnipresent secret police, his ruinous pact with Hitler, and his sudden death in 1953 dominate Deborah’s story. Without bringing the man himself into the frame, Trofimov shows how no corner of Ukrainian life escaped Stalin’s personalist rule. His regime of lies and fear annihilated trust and truth so thoroughly that Deborah wraps her starvation rations in state newspapers praising the triumphs of Soviet agriculture. His cruelty incentives Deborah’s neighbors to watch and inform, and bends her own children toward worship of the state. The man in Moscow exercises more decisive control over Deborah’s life than she does herself.

The sixth and final biography is that of Ukrainian women and, frankly, women throughout time and space. Early in the novel, during the halcyon days of hope in Kharkiv’s Motor Tractor Plant, Deborah’s friend Olena tells her that women are nothing without men and must attach themselves to men to survive. Deborah scoffs at such outdated nonsense in this new and progressive Soviet future, only to find that survival will require her to sacrifice her pride, her identity, her heritage, her body, mind, and soul to the fickleness of men. A woman’s love is worse than useless in a man’s world: it is dangerous.

But push a woman like Deborah too far, push a Ukrainian too far, and you’ll discover what hate means. Stalin’s Russians discovered this when forced to fight a postwar counterinsurgency in western Ukraine. Seven decades later, and one year after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Trofimov met a woman on the streets of Kyiv who told him, “You know, the really bad thing is that I really hate the Russians now. I never hated anyone in my life. And now I just can’t stop. I wish them the worst because of what they have done to us.” He just looked at her, and then they both began to cry.

“We are up against history,” says one of Trofimov’s characters. “History is a wild and bloodthirsty animal. It is on a rampage through this country again, breaking and remaking it anew. You can’t stand in its way, and you can’t stop it. All you can hope is that it misses you as it lashes out and claws its way forward. That it doesn’t notice you. That it crushes someone else.” Perhaps that’s true in a country not made for love; but once again, a nation is those who find a way to survive together. Having survived, they will live. And having lived, they will find their way back to love. “We will be happy again, sweetheart,” says Deborah’s mother Rebecca. “Despite them all, we will be happy again.”