What do you think?

Rate this book

128 pages, Paperback

First published December 12, 1976

"Cuanto mayor es la incongruencia, mayor es la verdad."Deslumbrado quedo por este inmenso libro de tan solo 119 páginas, por su belleza, por todo lo que encierra.

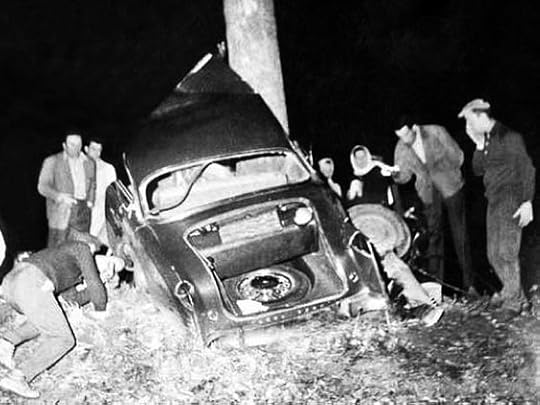

“Confía en mí, pero no me creas”, “No hay nada más importante que la existencia de lo que no existe”, “La vida imaginada es más satisfactoria que la vida recordada.”El relato es la carrera de un coche ocupado por dos hombres y la hija de uno de ellos que va aumentando la velocidad a medida que avanza; es un viaje pensado, diseñado, por el conductor pero en el que lo que al final ocurra (y esto me recordó a El ruletista, de Mircea) dependerá de la suerte, de que un coche pueda cruzarse en el camino, de que las ruedas resbalen en alguna curva, de que un peatón aparezca ante nosotros sin poder evitarlo. El conductor-narrador tendrá que salvar todos esos imprevistos hasta el final del viaje y conseguir el choque final, realizando así lo que para él sería una auténtica obra de arte, aunque solo una persona pueda abarcar el acto en toda su múltiple complejidad: la mujer del conductor, Honorine.

“En algún lugar deben de seguir

El rostro no visto de ella, su voz no oída.”