What do you think?

Rate this book

553 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1995

I do not want to think more than a day ahead; but the dreadful, wretched weight on my soul is there every morning. And my situation worsens every day.

One third said Yes out of fear, one third out of intoxication, one third out of fear and intoxication.

Lightning war [Blitzkrieg], final battle—superlative words. War and battle are no longer enough.

Göring: the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.

Himmler: The best political weapon is the weapon of terror. Cruelty commands respect.

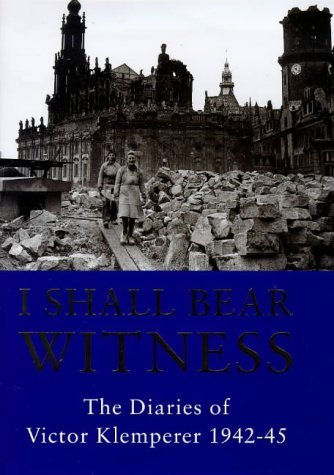

“Eva does not like to hear me talking about Hitler; I myself am as intensively concerned with him as a cancer researcher is with cancer.”This second translated volume of Victor Klemperer’s diaries, covers the years 1942-1945, which spans the period when the “Final Solution” was implemented through the months after WWII. In the first volume, Klemperer’s despair continued about the fate of him and his wife Eva continued to grow. His diary entries document the ever increasing number of indignities and threats the dwindling Jewish community faced. The instances of kindness they experienced were always tempered by fear. Oddly, Klemperer, on the one hand, makes clear that the Jewish community had intimate knowledge about the atrocities taking place in the concentration camps and in, as Timothy Snyder called them, the Bloodlands. Yet he wrote “the worst measures against [Jews] are concealed from the Aryans. Even people who are close to the Jews are not aware of the petty bullying or the brutal murders.”

Ausreichend für KZ und Fluchtversuch. (Sufficient for concentration camp and attempt to escape)

Meine [Tagebuch]-Lektüre ergibt immer entschiedener, daß LTI [Lingua Tertii Imperii] zur Publikation wesentlich geeigneter als das eigentliche [Tagebuch]. Es ist unförmig, es belastet die Juden, es wäre auch nicht in Einklang zu bringen mit der jetzt gültigen Opinio, es wäre auch indiskret.And so it was that his unfiltered report was made available to the general public only fifty years after the end of the war, in 1995, to massive success.

(My diary re-reading reinforces my conviction that LTI [Lingua Tertii Imperii] is much more suitable for publication tha the actual diary. It is unshaped, it puts a strain on [or: incriminate?] the jews, it wouldn't be compatible with the opinions prevalent today, it would also be indiscrete.)