Reading an early Simenon mystery today is as much entertainment as it is a trip into the past. This in especially true for Tropic Moon ("Coup de lune"), originally published in 1933, one of three novels set in Africa. It was also an early example of Simenon's "romans durs" - psychological dramas rather than a Maigret-type detective story that Simenon has been famous for. Having traveled and worked in several countries in Africa for much of 1932, Simenon's personal exposure to the harsh realities of French colonialism are, without doubt, manifest in this brief, intense, yet remarkable and very readable book.

The title of the novel hints at the story's intricacy. A term made up in analogy to "coup de soleil" (sunstroke), "coup de lune" suggests "moon stroke", inviting a comparison between the two in terms of the debilitating intensity on those exposed to it. The "victim" here is Joseph Timar, twenty-three years old, arriving in Gabon (then part of French Equatorial Africa) for a vacation - of sorts - from his bourgeois life in France. He is to manage his uncle's timber business set upcountry from the capital Libreville. But things don't turn out as planned. With a few sentences in the opening paragraphs of the novel, Simenon insinuates that Timar's stay will be anything but a vacation. While there is nothing tangible to justify the young man's apprehension - other than being alone in Africa for the first time - an atmosphere of anxiety and unease is established around the protagonist, as he stumbles innocently on an eerily artificial, yet very real, miserable colonialist community.

With transport upriver not ready for some time, Timar becomes increasingly entangled with the group of regular patrons of the "Central", the only hotel in town, and Adele, the seductive wife of its owner. With a few precise strokes, Simenon characterized this utterly bored, crude, and lowly collection of expatriates, whose main relaxation consists of alcohol, card games and the odd orgy with local women. While Africans are primarily seen as part of the backdrop, supplying services of various kinds, Simenon does not shy away from describing in some detail the insulting treatment that the Gabonese suffer by this group of whites. The overwhelming impression that the author expertly conveys is the dreariness, squalor and the desolation of the place. Slowly it dawns on Timar, who for the most part remains a naïve outsider, that the local white officials are no better than his drinking and gambling companions. When Thomas, the hotel's young African "boy" is murdered, the investigation is undertaken listlessly. While suspicions as to the culprit are rife, nobody really wants to act on them.

A major element amplifying the growing malaise experienced by Timar, is the sweltering heat of the tropical sun, that is stifling any initiative. This is a recurring theme throughout the novel. Simenon aptly employs it to reveal his hero's mental state as he goes through different stages of emotional upheaval and physical illness.

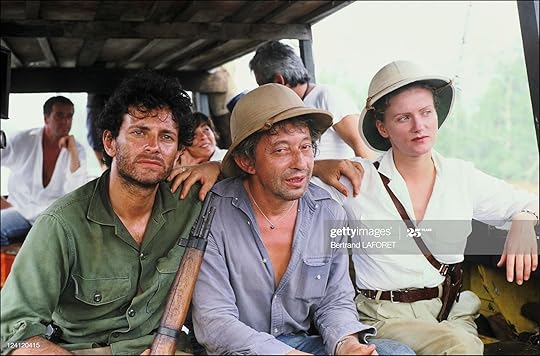

Timar's voyage upcountry, when it finally occurs, is not at all what he had anticipated. Could this be a new beginning? As dengue fever takes hold of him and he floats between reality and hallucination, events and context come into a new perspective and, for the first time, he sees more clearly what has been happening around him. Also for the first time, he experiences Africa and Africans directly and intimately. He is experiences "an immense feeling of peace, ...but peace tinged with sadness". While he cannot identify a focus his newfound "tenderness", "...it seemed to him that he was on the verge of understanding this land of Africa, which had provoked him so far to nothing but an unhealthy exaltation."

This new sense of freedom, understanding and confidence is bound to set him on an inevitable collision course with the white community in Libreville. Is there a compromise possible and what can Timar do? Simenon is unswerving in tone and perspective as he concludes the book consistent with the colonial reality of the time. Even after more than seventy years, Simenon's astute observations on French colonialism and his underlying harsh critique of the treatment of indigenous people and environments, are still relevant. Parallels to more recent historical circumstances come easily to mind. Thanks to the new NYRB edition and translation a wider audience have the opportunity to absorb this evocative story.