What do you think?

Rate this book

296 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 2013

Although this was only published in 2013 it already feels dated. Bullough arrived in Russia in 1999[*], the year which Putin became Prime Minister for the first time, and started his Dudko biography/journalistic observations at that point. Because of the biography aspect, we are looking back, for a good percentage of the book, into the last knockings of the Soviet years, with its KGB methods.

Although this was only published in 2013 it already feels dated. Bullough arrived in Russia in 1999[*], the year which Putin became Prime Minister for the first time, and started his Dudko biography/journalistic observations at that point. Because of the biography aspect, we are looking back, for a good percentage of the book, into the last knockings of the Soviet years, with its KGB methods.*Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin (Russian: Влади́мир Влади́мирович Пу́тин; IPA: [vɫɐˈdʲimʲɪr vɫɐˈdʲimʲɪrəvʲɪt͡ɕ ˈputʲɪn], born 7 October 1952) has been the President of Russia since 7 May 2012. Putin previously served as President from 2000 to 2008, and as Prime Minister of Russia from 1999 to 2000 and again from 2008 to 2012. During his last term as Prime Minister, he was also the Chairman of United Russia, the ruling party. wiki sourced

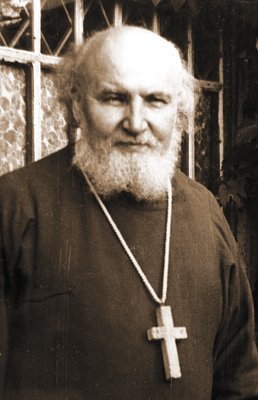

Fr. D Dudko

Fr. D Dudko Drinking themselves to death: Russia's alcoholism is a long-term consequence of collectivisation, the Gulag and the KGB.

Drinking themselves to death: Russia's alcoholism is a long-term consequence of collectivisation, the Gulag and the KGB.

Through the twentieth century, the government in Moscow taught the Russian shat hope and tust are dangerous, inimical and treacherous. That is the root of the social breakdown that has caused hte epidemic of alcoholism, the collapsing bith rate, the crime and the misery.