What do you think?

Rate this book

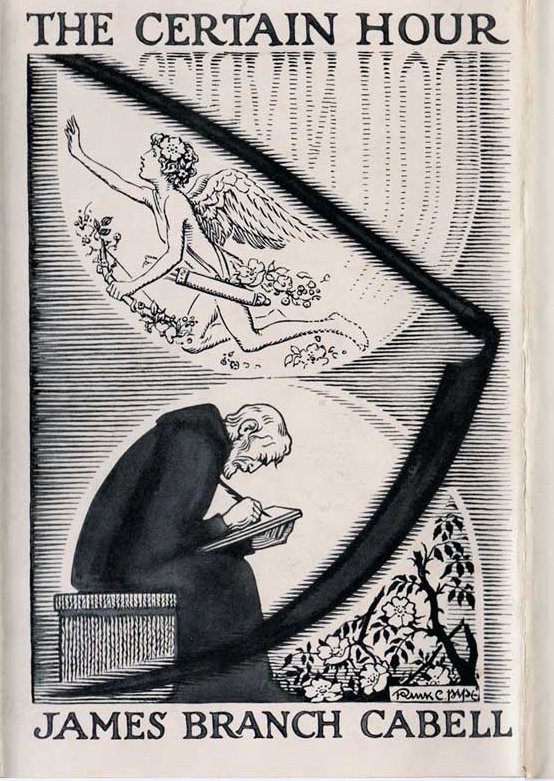

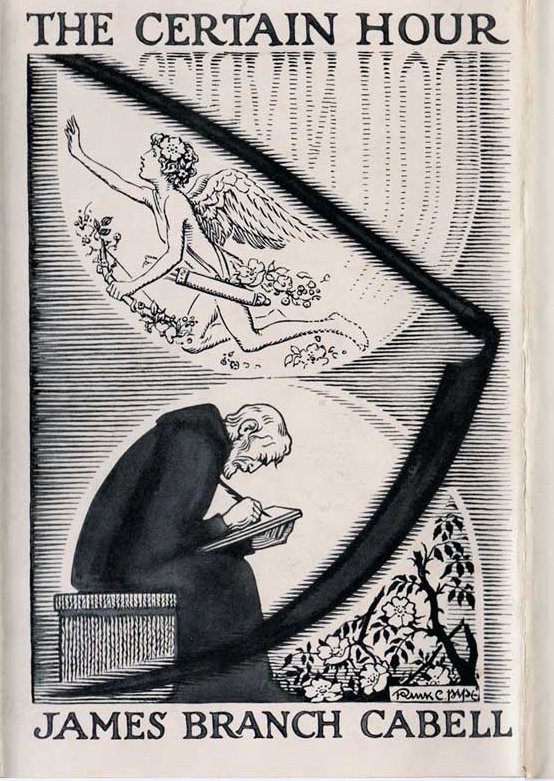

255 pages, Hardcover

First published January 1, 1916

Prince Fribble would have smiled, shrugged, drawled, “Eh, after all, the girl is handsome and deplorably cold-blooded!” Paul Vanderhoffen said, “I am not fit to live in the same world with her,” and wrote many verses in the prevailing Oriental style rich in allusions to roses, and bulbuls, and gazelles, and peris, and minarets — which he sold rather profitably.”

“I repeat to you,” the tutor observed, “that no consideration will ever make a grand-duke of me excepting over my dead body. Why don’t you recommend some not quite obsolete vocation, such as making papyrus, or writing an interesting novel, or teaching people how to dance a saraband? For after all, what is a monarch nowadays — oh, even a monarch of the first class?” he argued, with what came near being a squeak of indignation. “The poor man is a rather pitiable and perfectly useless relic of barbarism, now that 1789 has opened our eyes; and his main business in life is to ride in open carriages and bow to an applauding public who are applauding at so much per head. He must expect to be aspersed with calumny, and once in a while with bullets. He may at the utmost aspire to introduce an innovation in evening dress,—the Prince Regent, for instance, has invented a really very creditable shoe-buckle. Tradition obligates him to devote his unofficial hours to sheer depravity——”

“Our distinguished alumnus,” after being duly presented as such, had with vivacity delivered much the usual sort of Commencement Address. Yet John Charteris was in reality a trifle fagged.

“So I am going to develop into a pig,” he said, with relish,—“a lovable, contented, unambitious porcine, who is alike indifferent to the Tariff, the importance of Equal Suffrage and the market-price of hams, for all that he really cares about is to have his sty as comfortable as may be possible. That is exactly what I am going to develop into,—now, isn’t it?” And John Charteris, sitting, as was his habitual fashion, with one foot tucked under him, laughed cheerily. Oh, just to be alive (he thought) was ample cause for rejoicing! and how deliciously her eyes, alert with slumbering fires, were peering through the moon-made shadows of her brows!”

Pauline, I haven’t been entirely not worth while. Oh, yes, I know! I know I haven’t written five-act tragedies which would be immortal, as you probably expected me to do. My books are not quite the books I was to write when you and I were young. But I have made at worst some neat, precise and joyous little tales which prevaricate tenderly about the universe and veil the pettiness of human nature with screens of verbal jewelwork. It is not the actual world they tell about, but a vastly superior place where the Dream is realized and everything which in youth we knew was possible comes true. It is a world we have all glimpsed, just once, and have not ever entered, and have not ever forgotten. So people like my little tales. . . . Do they induce delusions? Oh, well, you must give people what they want, and literature is a vast bazaar where customers come to purchase everything except mirrors.