I’ve been waiting to read the play since I stumbled upon a quote from it in “Brainpickings” years ago:

“It’s to do with knowing and being known. I remember how it stopped seeming odd that in biblical Greek, knowing was used for making love. Whosit knew so-and-so. Carnal knowledge. It’s what lovers trust each other with. Knowledge of each other, not of the flesh but through the flesh, knowledge of self, the real him, the real her, in extremis, the mask slipped from the face. Every other version of oneself is on offer to the public. We share our vivacity, grief, sulks, anger, joy… we hand it out to anybody who happens to be standing around, to friends and family with a momentary sense of indecency perhaps, to strangers without hesitation. Our lovers share us with the passing trade. But in pairs we insist that we give ourselves to each other. What selves? What’s left? What else is there that hasn’t been dealt out like a deck of cards? Carnal knowledge. Personal, final, uncompromised. Knowing, being known. I revere that. Having that is being rich, you can be generous about what’s shared — she walks, she talks, she laughs, she lends a sympathetic ear, she kicks off her shoes and dances on the tables, she’s everybody’s and it don’t mean a thing, let them eat cake; knowledge is something else, the undealt card, and while it’s held it makes you free-and-easy and nice to know, and when it’s gone everything is pain. Every single thing. Every object that meets the eye, a pencil, a tangerine, a travel poster. As if the physical world has been wired up to pass a current back to the part of your brain where imagination glows like a filament in a lobe no bigger than a torch bulb. Pain.”

I did search for the text online (to no avail), and it seemed impossible to find a paper copy, so I left it at that, hoping that someday, somehow, I would have a chance to study the whole play.

There is a second-hand bookshop in Brussels that I particularly love. Called “The Ivory Monkey” (after an obscure Flemish novel), neatly tucked in the corner of a small square, it is stuffed to the brims with books in English, Dutch, French, and Spanish. A friend and I discovered it by pure chance two years ago and it so happens that I stumble upon a delightful little story every time I enter there.

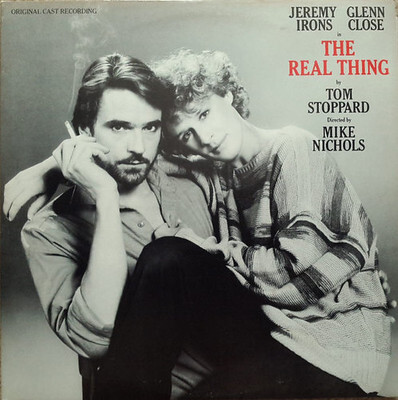

Last Saturday, as I was browsing a messy pile of books on the bookstore’s floor, “The Real Thing” finally showed its face.

“The Real Thing” is witty (but not earth-shatteringly so, mind you), a tad pretentious, and unfolds like a matryoshka doll. The words that initially hooked me – that brilliant definition of love I shared above – appeared when I least expected them, which made them that much sweeter: during a conversation between a quite cynical teenage daughter and her father (not a saint himself). Songs dispersed between the scenes include several deliciously kitschy 1960s pop hits (e.g. The Crystals – “Da Doo Ron Ron”, Herman’s Hermits – “I’m Into Something Good”, The Righteous Brothers – “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’, The Monkees – “I’m a Believer”), and I appreciate a good soundtrack. Also, there is nothing idealistic or grandiose about love and relationships - well, about humans in general, in this play. Flawed, often annoying characters, vulnerability and (a bit too) clever dialogues, that is what is on display, and it makes for quite the delightful read. I now hope I get the chance to actually see it played in a theatre.

Below, some more quotes that I’ve noted down:

***

HENRY: I’m supposed to be one of those intellectual playwrights. I’m going to look a total prick, aren’t I, announcing that while I was telling Jean-Paul Sartre and the post-war French existentialists where they had got it wrong, I was spending the whole time listening to the Crystals singing ‘Da Doo Ron Ron’.

***

HENRY: Yes, I’m not very up to date. I like Herman’s Hermits, and the Hollies, and the Everly Brothers, and Brenda Lee, and the Supremes… I don’t mean everything they did. I don’t like artists. I like singles.

MAX: This is sheer pretension.

HENRY: No. It moves me, the way people are supposed to be moved by real music. I was taken once to Covent Garden to hear a woman called Callas in a sort of foreign musical with no dancing which people were donating kidneys to get tickets for. The idea was that I would be cure of my strange disability. As though the place were a kind of Lourdes, except that instead of the front steps being littered with wooden legs, it would be tin ears. My illness at the time took the form of believing that the Righteous Brothers’ recording of ‘You’ve Lost that Lovin’ Feelin’ on the London Label was possibly the most haunting, the most deeply moving noise ever produced by the human spirit, and this female vocalist person was going to set me right.

***

ANNIE: Isn’t it awful? Max is so unhappy while I feel so… thrilled. His misery just seems… not in very good taste. Am I awful? He leaves letters for me at rehearsal, you know, and gets me to come to the phone by pretending to be my agent and people. He loves me, and he wants to punish me for his pain, but I can’t come up with proper guilt. I’m so irritated by it. It’s so tiring and so uninteresting. You never write about that, you lot. (…) Gallons of ink and miles of typewriter ribbon expended on the misery of the unrequited lover; not a word about the utter tedium of the unrequiting.

***

HENRY: I don’t know how to write love. I try to write it properly, but it just comes out embarrassing. It’s either childish or it’s rude. And the rude bits are absolutely juvenile. I can’t use any of it. My credibility is already hanging by a thread after Desert Island Discs. Anyway, I’m too prudish. Perhaps I should write it completely artificial. Blank verse. Poetic imagery. Not so much of the ‘Will you still love me when my tits are droopy?’ ‘Of course I will, darling, it’s your bum I’m mad for’, and more of the ‘By my troth, thy beauty makest the moon hide her radiance’, what do you think? (…) Loving and being loved is unliterary. It’s happiness expressed in banality and lust. It makes me nervous to see three-quarters of a page and no writing on it. I mean, I talk better than this.

ANNIE: You’ll have to learn to do sub-text. My Strindberg is steaming with lust, but there is nothing rude on the page. We just talk round it.

***

ANNIE: Well, why aren’t you ever jealous?

HENRY: Of whom?

ANNIE: Of anybody. You don’t care if Gerald Jones sticks his tongue in my ear – which, incidentally, he does whenever he gets the chance.

HENRY: Is that what this is all about?

ANNIE: It’s insulting the way you just laugh.

HENRY: But you’ve got no interest in him.

ANNIE: I know what, but why should you assume it?

HENRY: Because you haven’t. This is stupid.

ANNIE: But why don’t you mind?

HENRY: I do.

ANNIE: No, you don’t.

HENRY: That’s true, I don’t. Why is that? It’s because I feel superior. There is, poor bugger, picking up the odd crumb of ear wax from the rich man’s table. You’re right. I don’t mind. I like it. I like the way this presumption admits his poverty. I like him, knowing that that’s all there is, because you’re coming home to me and we don’t want anyone else. I love love. I love having a lover and being one. The insularity of passion. I love it. I love the way it blurs the distinction between everyone who isn’t one’s lover. Only two kinds of presence in the world. There’s you and there’s them. I love you so.

***

On (good and bad) writing:

HENRY: Where’s my cricket bat? (…) Shut up and listen. This thing here, which looks like a wooden club, is actually several pieces of particular wood cunningly put together in a certain way so that the whole thing is sprung, like a dance floor. It’s for hitting cricket balls with. If you get it right, the cricket ball will travel two hundred yards in four seconds, and all you’ve done is give it a knock like knocking the top off a bottle of stout, and it makes a noise like a trout taking a fly… What we’re trying to do is to write cricket bats, so that when we throw up an idea and give it a little knock, it might… travel… Now, what we’ve got here is a lump of wood of roughly the same shape trying to be a cricket bat, and if you hit a ball with it, the bat will travel about ten feet and you will drop the bat and dance about shouting ‘Ouch!’ with your hands struck into your armpits.

(…) Words don’t deserve that kind of malarkey. They’re innocent, neutral, precise, standing for this, describing that, meaning the other, so if you look after them you can build bridges across incomprehension and chaos. But when they get their corners knocked off, they’re no good any more, and Brodie knocks corners off without knowing he’s doing it. So everything he builds is jerry-built. It’s rubbish. An intelligent child could push it over. I don’t think writers are sacred, but words are. They deserve respect. If you get the right ones in the right order, you can nudge the world a little or make a poem which children will speak for you when you’re dead.

***

On (changing) politics:

HENRY: (…) But when he gets into his stride, or rather his lurch, announcing every stale revelation of the newly enlightened, like stout Cortez coming upon the Pacific – war is profits, politicians are puppets, Parliament is a farce, justice is a fraud, property is theft… It’s all here: the Stock Exchange, the arms dealers, the press barons… You can’t fool Brodie – patriotism is propaganda, religion is a con trick, royalty is an anachronism… Pages and pages of it. It’s like being run over very slowly by a traveling freak show of favourite simpletons, the india rubber pedagogue, the midget intellectual, the human panacea…

ANNIE: It’s his view of the world. Perhaps from where he’s standing you’d see it the same way.

HENRY: Or perhaps I’d realize where I’m standing. Or at least that I’m standing somewhere. There is, I suppose, a world of objects which have a certain form, like this coffee mug. I turn it, and it has no handle. I tilt it, and it has no cavity. But there is something real here which is always a mug with a handle. I suppose. But politics, justice, patriotism – they aren’t even like coffee mugs. There’s nothing real there separate from our perception of them. So if you try to change them as though they were something there to change, you’ll get frustrated, and frustration will finally make you violent. If you know this and proceed with humility, you may perhaps alter people’s perceptions so that they behave a little differently at that axis of behavior where we locate politics and justice; but if you don’t know this, then you’re acting on a mistake. Prejudice is the expression of this mistake.

***

ANNIE: I don’t feel selfish, I feel hoist. I send out waves, you know. Not free. Not interested. He sort of got under the radar. Acting daft on a train. Next thing I’m looking round for him, makes the day feel better, it’s like love or something: no – love, absolutely, how can I say it wasn’t? You weren’t replaced, or even replaceable. But I liked it, being older for once, in charge, my pupil. And it was a long way north. And so on. I’m sorry I hurt you. But I meant it. It meant something. And now that it means less than I thought and I feel silly, I won’t drop him as if it was nothing, a pick-up, it wasn’t that, I’m not that. I just want him to stop needing me so I can stop behaving well. This is me behaving well.

HENRY: If it was me – me and – I don’t know – Miranda Jessop – would you think I was a moralist of unique discrimination or just another cake-eater trying to have it?

ANNIE: I can’t say clever things. You say things better so you sound right. But I’m right about thing which you can’t say. This is the me who loves you, this me who won’t tell Billy to go and rot, and I know I’m yours so I’m not afraid for you – I have to choose who I hurt and I choose you because I’m yours. I’m only sorry for your pain but even your pain is the pain of letting go of something, some idea of me which was never true, an Annie who was complete in loving you and being loved back. Some Annie.